Bombing Because You Can: Operation Rolling Thunder

Part II: Military Coercion and the Misuse of Airpower

I saw our bombs as my political resources for negotiating a peace. On the one hand, our planes and our bombs could be used as carrots for the South, strengthening the morale of the South Vietnamese and pushing them to clean up their corrupt house, by demonstrating the depth of our commitment to the war. On the other hand, our bombs could be used as sticks against the North, pressuring North Vietnam to stop its aggression against the South.1 – President Lyndon Johnson

Operation Rolling Thunder, the U.S. bombing campaign over North Vietnam from 1965 to 1968, represents one of the most complex and contentious uses of air power in American military history. Planned as a limited and coercive strategy, the operation was aimed at pressuring North Vietnam to abandon its support for insurgencies in South Vietnam while avoiding full-scale war with the North's communist allies, China and the Soviet Union. The campaign highlighted deep-rooted disagreements within the U.S. leadership over using Air Power, reflecting ideological and strategic divides between civilian policymakers and military officials.

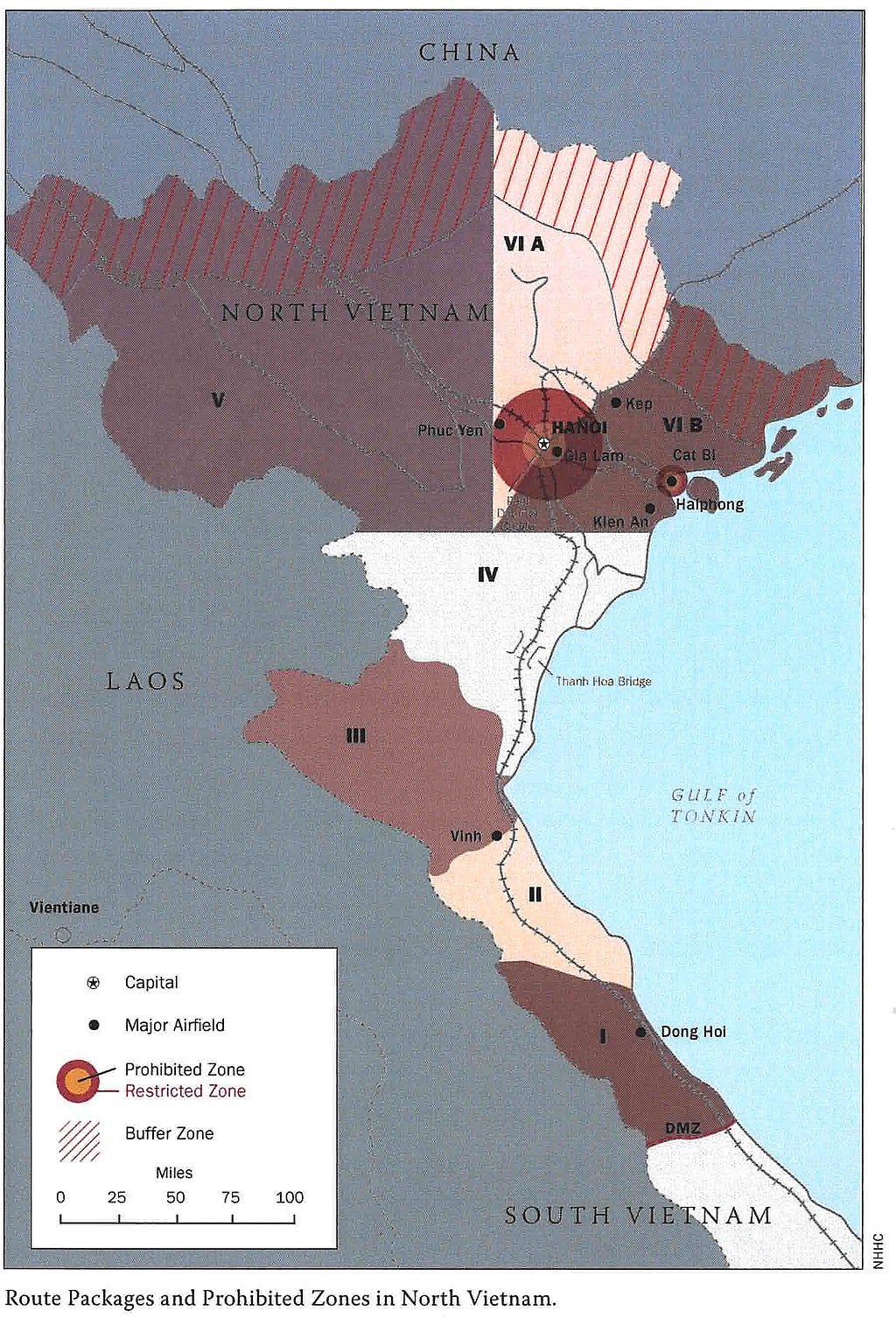

Operationally, Rolling Thunder focused on interdiction—targeting supply lines, infrastructure, and key military facilities. The campaign aimed to disrupt North Vietnam's support of the Viet Cong in the South by damaging roads, bridges, and supply depots. Yet, the strategy suffered from tactical constraints, such as micromanagement from Washington. President Johnson's need to control target selection to avoid provoking China or the Soviet Union stymied the operation's effectiveness. The multiple pauses and target reviews limited the sustained pressure needed for strategic impact. As the Pentagon Papers later revealed, Johnson's approach, which allowed “political and psychological considerations” to guide the campaign, diluted its military value.

Furthermore, the doctrinal divide over the roles of strategic bombing and counter-land (supporting ground forces) reflected the evolving nature of airpower theory in the Cold War. Unlike WWII, where strategic bombing was pursued in isolation, Rolling Thunder was a product of Cold War-era counterinsurgency, where air support was supposed to supplement a broader political strategy. More than anything, “Rolling Thunder was a trial by fire of the air power doctrine painstakingly developed during the previous three decades.”2 The use of close air support and interdiction theoretically should have helped U.S. and South Vietnamese ground forces by cutting off North Vietnamese supply routes like the Ho Chi Minh Trail. However, North Vietnam’s ability to adapt, using a vast network of tunnels, trails, and civilian labor, proved resilient against even the most intense bombing efforts.

The development of U.S. Air Force doctrine and theory regarding strategic and tactical airpower emerged strongly after the costly and ambitious strategic bombing campaigns of World War II and Korea. These campaigns, particularly in Europe and the Pacific, reflected early influences from theorists like Italian General Giulio Douhet, who argued for achieving victory by gaining air superiority and directly attacking enemy infrastructure and population centers. U.S. airpower advocates like Billy Mitchell championed strategic bombing, predicting it would shorten wars by targeting critical industries and breaking enemy morale. In WWII, U.S. bombing policy leaned toward precision strikes on infrastructure and military targets, while the British emphasized area bombing to disrupt German morale and economy broadly. However, the reality was more complex, as the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) concluded that although airpower contributed to weakening Axis powers, the impact on civilian morale and overall production was mixed and contentious. Influential figures, including economist John Galbraith and diplomat George Ball, criticized the bombing campaigns for inefficiency, noting that German production increased late in the war, suggesting that the air campaigns alone may not have been decisive. Post-war, this mixed assessment of airpower shaped U.S. Air Force (USAF) counter-land doctrine, which began focusing on combining strategic and tactical uses of airpower with ground operations, acknowledging that total victory likely required more than air dominance alone.

(Note: you can read Part 1 here, which details the strategic and tactical theory of air power and the American strategic bombing effort in World War II)

The counter-land doctrine centered on achieving air superiority and directly supporting ground operations through interdiction and close air support. Building on lessons from both World War II and Korea, the USAF aimed to isolate and destroy enemy ground forces before they could engage U.S. or allied troops. This doctrine emphasized air interdiction, targeting enemy supply lines, reinforcements, and infrastructure behind the front lines to weaken forces before they reached combat zones. Airmen defined interdiction as “the application of air power for the purpose of neutralizing, destroying or harassing enemy surface forces, resources and lines of communication” deep inside enemy territory.3 Close air support (CAS) became more refined, focusing on providing immediate aerial support to ground forces engaged in battle. The doctrine also saw a growing focus on joint operations with the Army, which ensured better integration of air assets in support of ground campaigns. This doctrine was less concerned with strategic bombing but broadly influenced tactics used during Rolling Thunder. Technological advancements, such as jet aircraft and precision-guided munitions, also shaped this doctrine by improving the effectiveness and accuracy of airstrikes, which remained core to the USAF’s counter-land strategy throughout the Cold War.

In security studies/international relations, “coercion” means efforts to change a state's behavior by manipulating costs and benefits.4 Military coercion is concerned with affecting political and military outcomes through indirect military measures such as aerial bombardments or naval blockades.5 Since the United States decided to pursue a limited war, it was logical that military coercion would become its primary tool to resolve the conflict. However, this created problems. As Henry Kissinger pointed out, “Doing too much and allowing the military element to predominate erodes the dividing line to all-out war and tempts the adversary to raise the stakes. Doing too little and allowing the diplomatic side to dominate risks submerging the purpose of the war in negotiating tactics and proclivity to settle for a stalemate.”6

The United States had already taken a significant role in Vietnam by early 1965. Still, the Gulf of Tonkin incident gave President Johnson political cover to pursue military action against the North. Even though he had decisively won the 1964 presidential election, he remained preoccupied with avoiding accusations from Republicans of being “soft on communism,” leading him to focus on air strikes as a course of action.7 It was simple, clean, and easy; the Navy could park aircraft carriers on “Yankee Station” while the Air Force could fly from the south, all the while avoiding the use of ground troops.8 But there were explicit risks in flying aircraft from bases in South Vietnam. On February 7, 1965, Vietcong guerillas attacked Camp Holloway, killing 7, wounding 104, and destroying or damaging 25 aircraft. It was at this moment that Johnson would fully embrace the air war.9 However, instead of addressing what was a significant policy change, Operation Rolling Thunder quietly began on March 2, 1965.10 At that moment, as one historian noted, “the credibility gap was born.”11

Two strategies emerged over the use of air power against North Vietnam, one advocated by the civilians and one endorsed by the military. The civilian strategy, named by one analyst the “lenient Schelling model,” opted to be limited to purely military and industrial targets while attempting to avoid inflicting casualties on the civilian population.12 This approach drew from Thomas Schelling's work on coercive warfare, which emphasized threatening adversaries into a political settlement with the potential for significant damage rather than immediately inflicting it. The key proponents of this scheme were Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, his assistant John McNaughton, the CIA Director John McCone, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Deputy National Security Adviser Walt W. Rostow, and Assistant Secretary of State William Bundy.13 A memo from McNamara on February 17, 1965, after a few air strikes (in retaliation for the Camp Holloway attack), is quite telling. He stated,

Although the four missions left the operations at the targets relatively unimpaired, I am quite satisfied with the results. Our primary objective, of course, was to communicate our political resolve. This, I believe we did.14

So, Rolling Thunder was less concerned about military effectiveness than sending a political message. But how could a political message be persuasive if its military implementation was ineffective? This would lead one historian to conclude, “by military standards, it was a bizarre campaign.”15

The military strategy, or the “genteel Douhet plan,” was primarily driven by Curtis Lemay, the Air Force Chief of Staff and the architect of the devastating firebombing campaign on Japan in World War II.16 Its cornerstone was to destroy the industrial war potential and maximize the damage to the political and social fabric of North Vietnam, holding all the hallmarks advocated by Douhet.17 They quite literally planned to “obliterate all industrial and major transportation targets as well as air defense assets” as efficiently and fast as possible.18 The more destruction, the better. However, this flew precisely in the face of what some of the data in the Strategic Bombing Survey and the Air Forces Official Histories on World War II concluded. Attempting to undermine the morale of an enemy civilian population was ineffective, whether they were targeted directly or indirectly. Bernard Brodie, one of the early thinkers on American nuclear strategy, was adamant about this point, writing,

There is no guarantee that a strategic bombing campaign would not quickly degenerate into pure terroristic destruction. The atomic bomb in its various forms may well weaken our incentive to choose targets shrewdly and carefully, at least so far as use of those bombs is concerned. But such an event would argue a military failure as well as a moral one, and it is against the possibility of such failure on the part of our military that public attention should be directed. What we have learned from the German experience is this: If we had to do the business all over again with the same weapons, we could do in a few months what in fact took us two years, and we would do it with far less destruction of urban areas and of civilian lives than occurred in Germany in the Second World War.19

In this aspect, Lyndon Johnson's civilian advisors seemed to take heart. Contrary to popular belief, the United States never engaged in large-scale urban bombing, with planes indiscriminately dropping conventional bombs on urban population centers. There were strict rules of engagement, and civilian oversight always checked targets, which aggravated military officers. At one point, President Johnson boasted, “they can’t even bomb an outhouse without any approval.”20 Thus, B-52 Bombers, including those from the highly trained Strategic Air Command (SAC), were mainly used in a tactical role in the South in Arc Light missions, supporting ground troops and bombing North Vietnamese supply routes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.21 The workhorses of the campaign were F-4 Phantoms and F-105 Thunderchiefs flown by the Navy and Air Force.

Even in an era when the U.S. military and defense bureaucracy began quantifying everything, many qualitative assumptions were made about a path to victory. Lemay stated that, “the military task confronting us is to make it so expensive for the North Vietnamese that they will stop their aggression against South Vietnam and Laos. If we make it too expensive for them, they will stop.”22 This bold statement completely dismissed the reality that North Vietnam had a say in the matter.

There were flaws in both strategies. The civilian strategy failed to account for the fact that the North had little domestic industry contributing to its war effort, and China or the Soviet Union could simply supply military and civilian supplies. The military strategy assumed that the North Vietnamese government would be compelled to negotiate after a certain number of targets (of which there were few) were destroyed. This assumption was like the Army strategy, which believed that reaching the “crossover point”—where enemy soldiers were being killed faster than they could be replaced—would also force the North Vietnamese government to the negotiating table. Both disregarded the agency of the North Vietnamese government and the people. As former CIA analyst Merle Pribbenow found, North Vietnam had an ample and robust propaganda machine that exposed the worst of the bombings to the outside world and kept morale fixated on participating in the “people’s war.”23 Both strategies faced problems because neither civilians nor the military could decide whether military or diplomatic objectives should be met first, given that it was a limited war. This stemmed from Rolling Thunder being a “comparatively risky and politically sensitive component of U.S. strategy,” concluded the Pentagon Papers.24

A small group of skeptics within the administration believed bombing would accomplish nothing. George Ball, the Undersecretary of State, was the most prominent official. He was a member of the Strategic Bombing Survey during World War II and thought the strategic bombing campaign had generally been ineffective, given the resources and costs. Ball argued that because North Vietnam did not have any air force (at least at that point in 1965), it was only logical that a response would be to escalate the ground war in the South.25 In addition, any U.S. military presence would merely increase the dependency of South Vietnam’s government on the U.S. and make it harder to disengage. Was that really worth boosting “morale”? This, in his view, was a half-measure at best. Another skeptic was Clark Clifford, a seasoned Washington insider and trusted confidant of Johnson, who believed the military's assessments and projected outcomes presented to the president were overly optimistic and grounded in wishful thinking.26 It was as if North Vietnam could be compelled to comply simply by dropping enough bombs and destroying sufficient targets. Clifford repeatedly questioned, what if they still refuse to negotiate after these targets are destroyed? The military brass did not have an answer. Unfortunately, Ball and Clifford were a small minority, ultimately being right but not positioned or influential enough in the bureaucracy to force a significant change.

President Johnson, who viewed the campaign as a means of “negotiating with bombs,” saw air power as a tool to encourage South Vietnamese reform while coercing North Vietnam into diplomacy. This “carrot-and-stick” approach was complex and challenging to execute. National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, the most prominent civilian advocate of Rolling Thunder, warned President Johnson in a memo at the end of December 1965 that,

Air attack against lines of communication is extremely difficult in this part of the world. It is clear that air interdiction at any one point can be circumvented by the Viet Cong/North Vietnamese forces and all local obstacles can be overcome by ingenuity and hard work, both of which they display in ample quantities. Therefore, our only hope of a major impact on the ability of the North Vietnamese to support the war in Vietnam is continuous air attack over the entire length of their lines of communication from the Chinese border to South Vietnam, and within South Vietnam.27

That was a vast amount of territory to cover spread over 4 different countries, a near impossible ask even for the best air force in the world. Johnson was wary of escalation that could bring China or even the Soviet Union into the conflict. Thus, he micromanaged the process to the point where he picked out targets every few weeks and had to be cleared through several layers of bureaucracy from the theatre command to the Pentagon and eventually to the White House, which Air Force officials criticized. At one point, the Joint Chiefs revised the target list every two weeks, sending it to the White House and Pentagon for review by the National Security Council and the “whiz kids” in McNamara’s office before approval.28 The Pentagon Papers noted that “target selection had been completely dominated by political and psychological considerations” rather than strategic military objectives.29 The micromanagement also led to several pauses in bombings, which sparked heated debates within the administration, to the point that they were rehashing the decision to launch Rolling Thunder in the first place.30

By mid-1965, it was evident that Rolling Thunder was not working, but it wasn’t because of a lack of trying. The number of attack sorties, including both strike and flak suppression missions, had increased to over 500 per week, with the total sorties flown rising to around 900 per week—four to five times the amount at the campaign's outset.31 The CIA director, John McCone, had written a memo to President Johnson in April 1965, less than a month after Rolling Thunder stating,

The strikes to date have not caused a change in the North Vietnamese policy of directing Viet Cong insurgency, infiltrating cadres, and supplying material. If anything, the strikes to date have hardened their attitude.32

However, instead of recommending a de-escalation, McCone proposed the opposite,

We must hit them harder, more frequently, and inflict greater damage. Instead of avoiding the MIG’s, we must go in and take 'them out. A bridge here and there will not do the job. We must strike their airfields, their petroleum resources, power stations, and their military compounds. This, in my opinion, must be done promptly, and with minimum restraint.33

McCone quickly came to believe that the civilian “Schelling” strategy he initially supported was failing and shifted his support to the “genteel Douhet plan.”34 This shift aligned with a surge in U.S. troop deployments, escalating combat operations, and rising casualty numbers. The escalation in the air and on the ground appeared to be exasperating the violence rather than curbing it, precisely the opposite of what policymakers wanted to happen. This raised a persistent question, highlighted by the Pentagon Papers: could the U.S. continue escalating the bombing, upholding a credible threat of further action all the while simultaneously pursuing negotiations?35

As the bombing campaign intensified, oscillating between civilian and military strategies, the intelligence community began evaluating its tangible effects, producing detailed assessments on the damage to North Vietnam's infrastructure and warfighting capabilities. A monthly report compiled by the CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) provided a running tally of the estimated dollar amount for repairing or reconstructing damaged or destroyed facilities and equipment. Here's an excerpt as an example,

Power Plants. 6 small plants struck, only 2 of them in the main power grid. Loss resulted in local power shortages and reduction in power available for irrigation but did not reduce the power supply for the Hanoi/Haiphong area.

POL storage. 4 installations destroyed, about 17 percent of NVN's total bulk storage capacity. Economic effect not significant, since neither industry nor agriculture is large user and makeshift storage and distribution procedures will do.

Manufacturing. 2 facilities hit, 1 explosive plant and 1 textile plant, the latter by mistake. Loss of explosives plant of little consequence since China furnished virtually all the explosives required. Damage to textile plant not extensive.

Bridges. 30 highway and 6 railroad bridges on JCS list destroyed or damaged, plus several hundred l lesser bridges hit on armed reconnaissance missions. NVN has generally not made a major reconstruction effort, usually putting fords, ferries, and pontoon bridges into service instead. Damage has neither stopped nor curtailed movement of military supplies.

Railroad yards. 3 hit, containing about 10 percent of NVN's total railroad cargo-handling capacity. Has not significantly hampered the operations of the major portions of the rail network.

Ports. 2 small maritime ports hit, at Vinh and Thanh Hoa in the south, with only 5 percent of the country's maritime cargo-handling capacity. Impact on economy minor. Locks. Of 91 known locks and dams in NVN, only 8 targeted as significant to inland waterways, flood control, or irrigation. Only 1 hit, heavily damaged.36

During its first year, Rolling Thunder supposedly caused $63 million ($568 million in today’s money) in measurable damage, including $36 million to “economic” targets such as bridges and transport equipment and $27 million to “military” targets like barracks and ammunition depots.37 But what did this all amount to and mean? That question continued to befuddle the military because, at least on paper, the Air Force and Navy was inflicting severe punishment on the North. Yet, the intelligence agencies were meeting these claims with skepticism. As a CIA memorandum acknowledged, “the cost-effectiveness of the air campaign declined” as the number of fixed targets decreased.38 But the more worrisome conclusion by the same memo was that “North Vietnam, in the short term at least, will apparently take no positive step toward a negotiated settlement,” which was the central goal of the air campaign.39 North Vietnam had met every escalation; they had expanded their air defenses on the ground by nearly 250%, along with new squadrons of MIG fighter jets with Soviet-trained crews to engage American jets directly in the air.40 Even with the most advanced fighter jets in the world, the USAF still had to conduct World War II-style air attacks because “smart” bombs were only developed later in the war, leaving them vulnerable to conventional anti-aircraft weapons and Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missiles.41

By the summer of 1966, the Pentagon Papers also concluded that after a year and a half of Rolling Thunder, there was no measurable direct impact on Hanoi's ability to carry out and maintain military operations in the South at its existing level.42 It was sobering given that in 1966, 148,000 sorties were flown and 128,000 tons of bombs were dropped, compared to 55,000 sorties and 33,000 tons of bombs in 1965; the number of fixed targets struck increased from 158 to 185, leaving only 57 unstruck out of a list of 242.43 It was clear the campaign had devolved into a process where conducting operations became its own objective. Sorties, bombing volume, and targets destroyed were the primary metrics for progress. However, all these numbers merely measured the campaign's efficiency rather than its effectiveness.

At the end of 1966, Secretary McNamara was fully convinced that Rolling Thunder was futile and recommended offramps such as halting the air war altogether and putting resources into physical barriers in South Vietnam to stop the flow of troops. Indeed, as 1966 came to a close, the USAF had upped the number of aircraft, sorties, and bombs, and yet the United States was back where it had started when the campaign began.

1967-1968 was marked by the debate over whether to escalate or try to find an off-ramp. The military wanted to escalate, while Secretary McNamara and other civilian officials wished to lower the bombing. In examining the civil-military relationship in the context of Rolling Thunder, the failure of senior military officials and the principal civilian leader in the Pentagon to align on strategic objectives left President Johnson in a bind.44 President Johnson attempted a middle path, facing pressure from both sides, gradually escalating the bombing in late spring 1967 but then leveling off during the summer. This approach was difficult to maintain as it neither fully satisfied any faction nor offered a clear path to a breakthrough. Unfortunately, the “breakthrough” came when the North launched the Tet Offensive in January 1968. By then, domestic opposition had reached a crescendo as the “light at the end of the tunnel,” famously proclaimed by General William Westmoreland, blew up in his face. The optimism was shattered as stark images of the war, including the assault on the U.S. Embassy, flooded American television screens, undermining public confidence and further fueling anti-war sentiment that eventually led President Johnson to opt not to run for reelection and halt the bombing with nothing to show for it.

Was Operation Rolling Thunder doomed to fail? Some believe so. Dr. Robert Pape, a leading scholar on air power and military coercion, wrote thirty years after the war, “I believe that North Vietnam during the Johnson years was essentially immune to coercion with air power.”45 Another historian observed that the bombing campaign had “barely bruised” North Vietnam.46 In other words, even if the U.S. had conducted a World War II-style “dehousing” or firebombing campaign to inflict maximum civilian casualties, the outcome likely would have been no different.47 If we take Daniel Byman’s and Matthew Waxman's definition of military coercion, “getting the adversary to act a certain way via anything short of brute force; the adversary must still have the capacity for organized violence but choose not to exercise it,” then Rolling Thunder was a complete failure.48

Between March 1965 and November 1968, USAF aircraft conducted 153,784 attack sorties against North Vietnam, with the Navy and Marine Corps contributing an additional 152,399 sorties.49 By the end of 1967, the Department of Defense reported that 864,000 tons of American bombs had been dropped on North Vietnam, roughly the size of California, during Rolling Thunder.50 This exceeded the 653,000 tons dropped during the Korean War and the 503,000 tons dropped in the Pacific theater during World War II.

In addition, during the whole bombing period, the value of economic resources obtained through foreign aid exceeded the losses incurred due to the bombing. The cumulative increase in foreign aid amounted to $490 million, while total losses reached $294 million.51 Ironically, John Galbraith's conclusions from his work on the Strategic Bombing Survey 20 years earlier proved prescient: strategic bombing appeared to inspire innovation and mobilization in the adversary rather than incapacitating it.52 In the case of North Vietnam, however, this adaptation manifested not through domestic production but through increased reliance on foreign support. Any impact on North Vietnam’s manpower was offset by population growth and foreign labor. An estimated 40,000 Chinese were employed in maintaining North Vietnam's road and rail network in addition to an ample number of Soviet and Chinese military advisors.53 North Vietnam’s morale was never shaken to the point where it sought to negotiate “in good faith” as the Johnson administration envisioned.54

As much as Rolling Thunder was a failure for the military, it was also a failure for the “Best and the Brightest,” the defense intellectual class that emerged after World War II and dominated Cold War Policy. As one historian noted, Rolling Thunder “revealed that the concept of force underlying all their formulations and scenarios was an abstraction and practically useless as a guide to action.”55 It would take years for many to acknowledge the futility of the effort.

Ultimately, Operation Rolling Thunder demonstrated the limitations of air power as a standalone strategy in a limited war. North Vietnam’s resilience, the adaptability of its logistics network, and its external support from China and the Soviet Union rendered the bombing campaign strategically incohesive. The campaign’s inability to compel North Vietnam to the negotiating table or halt its support for the insurgency in the South reflected broader shortcomings in U.S. strategy during the Vietnam War: a lack of clear objectives, underestimation of the adversary’s resolve, and failure to fully integrate military operations with diplomatic goals.

Moreover, Rolling Thunder showcased a persistent divide between civilian policymakers and military strategists over the proper use of airpower. Civilian leaders, constrained by Cold War geopolitics and wary of provoking a more significant conflict, opted for a restrained and highly controlled campaign. At the same time, military advocates pushed for a more aggressive application of airpower, believing it could force a swift resolution. This dissonance epitomized the challenges of using military coercion in a complex and politically sensitive conflict. The operation's legacy, alongside other aspects of the Vietnam War, underscores the critical importance of aligning military actions with realistic political objectives and understanding the adversary’s capacity to endure and adapt. Rolling Thunder’s failure served as a cautionary tale for future military interventions, emphasizing the need for clarity in strategy, coherence in execution, and humility in the face of an adversary’s resolve and ingenuity.

References

Berger, Carl. 1977. The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History.

Bird, Kai. 1998. The Color of Truth McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy: Brothers in Arms. New York: Touchstone.

Brodie, Bernard. 1950. "Strategic Bombing: What can it do?" The Reporter 28-31.

Drew, Dennis M. 1986. ROLLING THUNDER 1965: Anatomy of a Failure. Cadre Paper, Maxwell Air Force Base: Air University Press.

Ellsworth, John. 2003. OPERATION ROLLING THUNDER: STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS OF AIRPOWER DOCTRINE. Strategy Research Project, Carlisle: U.S. Army War College.

Force, Vietnam Task. 1969. Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force. Washington: Department of Defense.

Halberstam, David. 1973. The Best and the Brightest. New York: Ballantine Books.

II, Merle L. Pribbenow. 2001. "Rolling Thunder and Linebacker Campaigns: The North Vietnamese View." The Journal of American-East Asian Relations Vol. 10, No. 3/4 197-210.

Jackson, Phil Haun and Colin. 2016. "Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II." International Security, Vol. 40, No. 3 139-178.

Kaplan, Fred. 1991. The Wizards of Armageddon. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Karnow, Stanley. 1983. Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin Books.

Kissinger, Henry. 1995. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

MacKinlay Kantor, Curtis Lemay. 1965. Mission with LeMay. Garden City: Doubleday.

Pape, Robert A. 1996. Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Pape, Robert A. 1990. "Coercive Air Power in the Vietnam War." International Security Vol. 15, No. 2 103-146.

Patterson, David C. Humphrey and David S. 1998. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968, Volume III, Vietnam, June-December 1965. Washington: Government Printing Office.

—. 1998. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume IV, Vietnam, 1966. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Rhynedance, George H. 2000. McNamara vs. the JCS Vietnam's Operation ROLLING THUNDER: A Failure in Civil-Military Relations. Strategy Research Project, Carlisle: U.S. Army War College.

Smith, Melden E. 1977. "The Strategic Bombing Debate: The Second World War and Vietnam." Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 12, No. 1 175-191.

Thompson, Wayne 2002. To Hanoi and Back: The U.S. Air Force and North Vietnam, 1966–1973. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press

Waxman, Daniel L. Byman and Matthew C. 2000. "Kosovo and the Great Air Power Debate." International Security Vol. 24, No. 4 5-38.

Quoted from, Dennis M. Drew ROLLING THUNDER 1965: Anatomy of a Failure (Cadre Paper, Maxwell Air Force Base: Air University Press, 1986), 31.

Ibid., 3.

U.S. Air Force, Joint Air-Ground Operation, Tactical Air Command Manual 55-3 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Air Force, September 1, 1957), 15. From Phil Haun and Colin Jackson. "Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II." International Security, Vol. 40, No. 3 (2016): 142.

Robert A. Pape, "Coercive Air Power in the Vietnam War." International Security Vol. 15, No. 2 (1990): 106.

Ibid., 106.

Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 480.

After all, Johnson had been in the Senate at the height of McCarthyism.

David Halberstam, The Best and the Brightest (New York: Ballantine Books. 1973), 538.

After this, U.S. combat troops would also arrive, marking another critical turning point.

That decision stunned the National Security Council.

Kai Bird, The Color of Truth McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy: Brothers in Arms (New York: Touchstone, 1998), 309.

Robert A. Pape Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 178.

McNaughton, in particular, was a dedicated devotee of Schelling.

Vietnam Task Force, “[Part IV. C. 3.] Evolution of the War. ROLLING THUNDER Program Begins: January - June 1965, Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force. Washington: Department of Defense. (1969), 64. Cited as the “Pentagon Papers” with Volume names.

Fred Kaplan, The Wizards of Armageddon (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), 336.

Pape, Bombing to Win, 180.

See Pape for more details, Bombing to Win, 180-181.

Pape, Bombing to Win, 180.

Bernard Brodie, "Strategic Bombing: What can it do?" The Reporter (1950): 31.

Quoted from Stanley Karnow. Vietnam: A History (New York: Penguin Books. 1983), 430.

Melden E Smith, "The Strategic Bombing Debate: The Second World War and Vietnam." Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 12, No. 1 (1977): 182.

Mackinlay Kantor and Curtis Lemay. Mission with LeMay (Garden City: Doubleday. 1965), 564.

Merle L. Pribbenow II, "Rolling Thunder and Linebacker Campaigns: The North Vietnamese View." The Journal of American-East Asian Relations Vol. 10, No. 3/4 (2001): 197-210.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 2.

Halberstam, 499-500.

Clifford was also chairman of the Presidential Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board.

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968, Volume III, Vietnam, June-December 1965. (Washington: Government Printing Office. 1998), Document 245.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. b.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume II, (1969), 100.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 3.] Evolution of the War. ROLLING THUNDER Program Begins: January - June 1965, 5.

See Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 20-43

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 2.

Pentagon Papers, [Part IV. C. 3.] Evolution of the War. ROLLING THUNDER Program Begins: January - June 1965, 91.

Pentagon Papers, [Part IV. C. 3.] Evolution of the War. ROLLING THUNDER Program Begins: January - June 1965, 92.

According to the Pentagon Papers, it’s unclear if the President ever saw or discussed this memo with McCone.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 5.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 53.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 52.

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume IV, Vietnam, 1966. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1998), Document 292.

Ibid., Document 292.

Pribbenow, 200.

Smith, 184-185.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 150.

Pentagon Papers, “[Part IV. C. 7. a.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume I.” 177.

George H. Rhynedance, McNamara vs. the JCS Vietnam's Operation ROLLING THUNDER: A Failure in Civil-Military Relations. Strategy Research Project, (Carlisle: U.S. Army War College. 2000), 10.

Pape, Bombing to Win, 176.

Karnow, 431.

For example, the dikes along the Red River, which if destroyed, would have killed thousands of people, were never targeted.

Kaplan, 336.

Wayne Thompson, To Hanoi and Back: The U.S. Air Force and North Vietnam, 1966–1973 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press 2002), 303.

Carl Berger, The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973 (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History 1977), 366.

Pentagon Papers, [Part IV. C. 7. b.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume II, 128.

Pentagon Papers, [Part IV. C. 7. b.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume II, 130.

Pentagon Papers, [Part IV. C. 7. b.] Evolution of the War. Air War in the North: 1965 - 1968. Volume II, 143.

Daniel L. Byman and Matthew C. Waxman "Kosovo and the Great Air Power Debate." International Security Vol. 24, No. 4 (2000); 9.

On the diplomatic side as a State Department officer I remember hearing that the lesson of the bombing campaign was that ‘if you want to send a message, use a telegram”. There was also the clear demonstration year in and year out that Hanoi understood that, like the French the Americans would eventually go home but the Vietnamese would still be there. In the pre-precision guided weapons era of Desert Storm the bombing campaign seriously undermined the strategic bombing mavens while the downed air crew in captivity offered Hanoi more bargaining chips.

Thanks for the well-researched and interesting article, I was especially interested to learn about Ball and Clifford's objections. The use of airpower in smaller wars is important to study.