In the summer of 1914, Europe stood on the brink of a war that would redefine the course of history. At the heart of this conflict lay a complex and controversial military strategy—the Schlieffen Plan. Conceived as a means to quickly defeat France before turning eastward to face Russia, this bold blueprint relied on rapid maneuvering, a swift offensive through Belgium, and the hopes of avoiding a prolonged two-front war. Yet, as history would prove, the Schlieffen Plan was riddled with strategic pitfalls, diplomatic miscalculations, and an unrealistic belief in swift victories. What if the German General Staff had shifted its focus to the East, opting for a defensive stance in the West and a decisive strike against Russia? Would Germany have had a better chance to win the war? Would not violating Belgium’s neutrality keep Britain out of the war, thereby limiting the number of enemies Germany would have? Would a more cautious, defensive approach have spared Germany from the protracted nightmare of trench warfare? This analysis reimagines the alternatives to the Schlieffen Plan and explores how the General Staff's refusal to adapt ultimately doomed their quest for victory.

Germany’s rise had been marked by the German Statesmen Otto von Bismarck’s careful maneuvering of European power politics, which ensured that coalitions would not intervene or serve a check.1 After Bismarck’s departure, the Franco-Russian Alliance officially signed in 1894, upsetting that careful balance and creating the nightmare strategic scenario for Germany: a war on two fronts. Bismarck had anticipated the repercussions of Germany’s great military victories and, in 1876, attempted to prevent a European coalition unsuccessfully. He sought a guarantee from Russia to maintain Alsace-Lorraine as part of Germany in exchange for Germany’s unconditional support of Russian policy in the East. But by 1894, Bismarck was out of the picture, and lesser men who could not prevent the European powers from inevitably marshaling against them had taken his place. From then on, the German Military would spend the next two decades trying to solve this problem.

Alfred von Schlieffen was appointed the Chief of the Imperial German General Staff in 1891. A “shy and reserved man,” as one historian described him, Schlieffen wasn’t a political general, but he did believe in “military necessity.”2 In other words, the General Staff should have extensive input on all aspects of policy related to the security of the German state. The General Staff had a host of contingencies for confrontations on the European continent, but the one that continued to befuddle them was a war in which they would be forced to confront Russia in the East and France in the West simultaneously. As large as their army was, it was impractical to expect they could simply split their forces in half and win.

Schlieffen eventually devised a plan that would become infamously known as the Schlieffen Plan.3 In so many ways, it was the German way of war; an “offensive campaign, designed to seize the initiative, to exploit fleeting opportunities, and to achieve a decisive victory by the rapid annihilation of the opponents' military forces.”4 In practice, the Schlieffen plan aimed to avoid a prolonged two-front war by defeating France before turning to fight Russia. The plan involved a rapid invasion of France through neutral Belgium and the Netherlands, bypassing French defenses and destroying the French Army in a grand encirclement.5 Afterward, German forces would shift east to confront Russia, which was expected to mobilize more slowly. Henry Kissinger would remark that the plan was, “as brilliant as it was reckless.”6 Another analyst called it “an armchair strategist’s dream.”7 The foundation of the Schlieffen Plan hinged on the German military’s fundamental belief that “any war against Russia would certainly be long and indecisive.”8 There is still a robust historical debate to the extent that Schlieffen and other German officers trusted the veracity of their plan or if they could even win a great European war. The destruction and taking of documents during World War II have left historians still trying to piece together the plan.9

The Eastern Plan

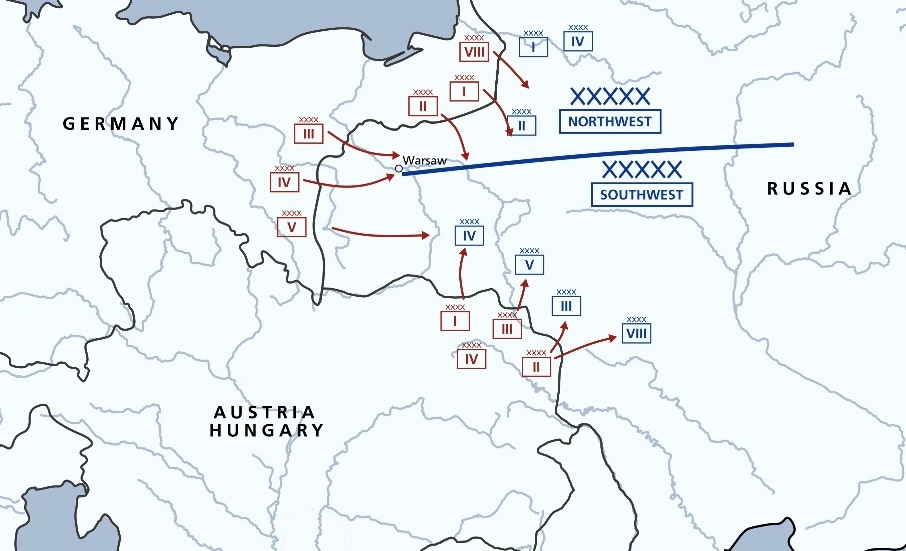

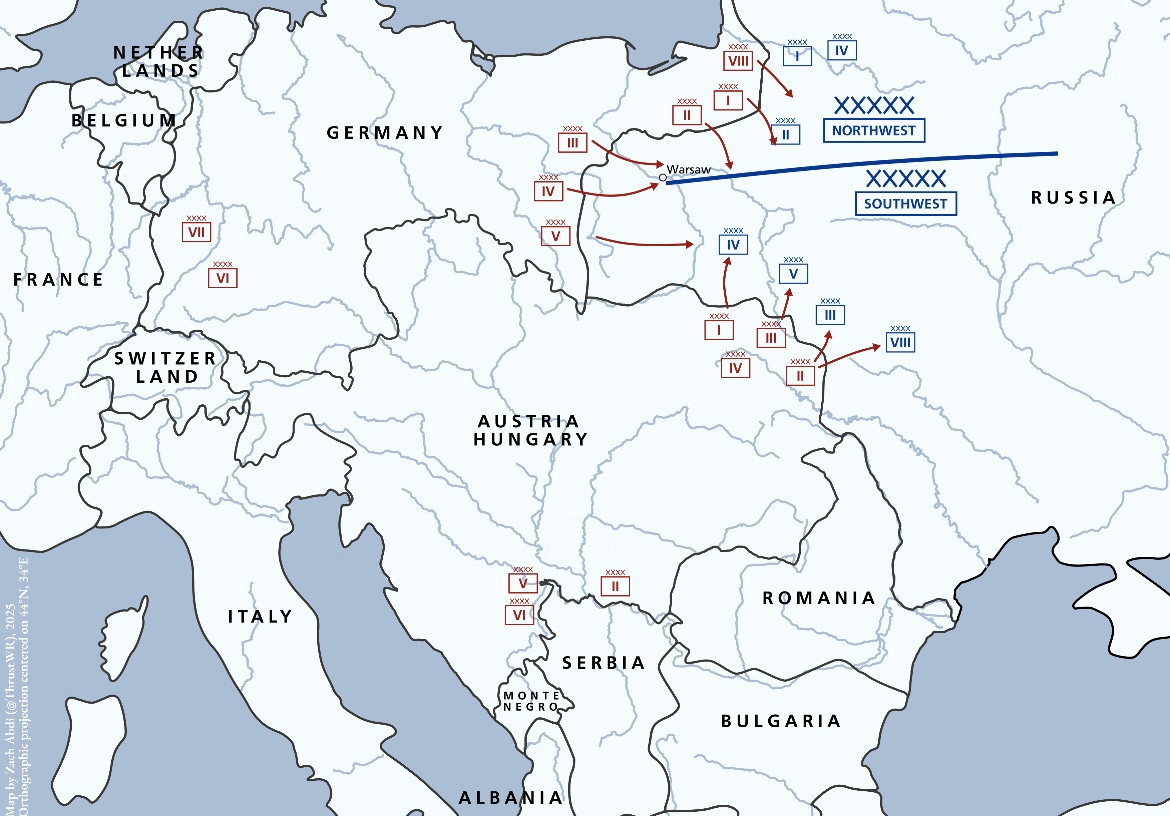

A Schlieffen Plan directed against Russia would have required the Germans to mobilize their forces rapidly along their eastern border, leveraging their existing rail networks to ensure swift movement of troops and supplies. Instead of committing resources to a Western offensive, the German High Command would have concentrated its efforts on delivering a hard blow to Russia's underprepared armies. This strategy would have twofold objectives: to put themselves in a strong position to reach a settlement in the East against Russia and keep Britain from intervening on behalf of the Allies by not violating Belgium's neutrality.

The initial German deployment would involve a tightly coordinated advance aimed at encircling and destroying the nearest Russian formations. Brest-Litovsk would serve as a critical operational target due to its strategic location as a major railway hub and supply depot. German forces would likely focus on exploiting the gaps between Russian armies, using superior maneuverability and centralized command to isolate and overwhelm enemy units.

The 8th Army, already stationed in East Prussia, could serve as a screening force, holding off Russian advances and protecting the flanks of the leading German offensive. Meanwhile, some of the 1st Army and a calvary corps might spearhead a deep penetration to cut off Russian reinforcements and prevent the 1st and 2nd Russian Armies from consolidating their positions. By targeting logistical centers and rail hubs, the Germans would aim to cripple Russian supply lines, further straining an already overstretched military.

The Germans would likely capitalize on Russia's well-documented logistical and organizational weaknesses, particularly its limited ability to supply large formations over vast distances. While Russia's rail improvements presented a potential advantage, German planners might have seen this as an opportunity to capture and repurpose existing rail infrastructure for their own operational needs, creating supply routes into the Russian heartland.

Key secondary objectives would include securing Poland's territory to create a defensible eastern buffer and neutralizing Russian forces in the vicinity of Warsaw and the Masurian Lakes. Once initial successes were achieved, German forces could pivot toward deeper penetrations into Russian territory, aiming to force the Tsarist regime into a negotiated settlement or even to destabilize the political order entirely, as had been demonstrated in the Russo-Japanese War. This would not happen in months, of course, but doing so as quickly as possible could bring an end to the war by late 1915 or early 1916.

Such an eastern Schlieffen Plan, however, would require an unprecedented level of coordination, reliance on rail logistics, and an acceptance of potentially higher casualties as the campaign stretched into the Russian interior. The vast distances and the difficulties posed by terrain, weather, and Russian resistance would make success far from guaranteed, underscoring the immense gamble inherent in such a strategy.

The role of the Austro-Hungarian Army would be critical, as its forces would need to act in close coordination with the German armies to ensure the campaign's success. The Austro-Hungarian Army, already committed to defending the empire's extensive eastern front, would be tasked with holding the Russian forces in Galicia and preventing them from diverting attention toward the main German offensive.

The Austro-Hungarians would likely focus on engaging Russia's 3rd and 8th Armies, which were historically stationed in Galicia, thereby tying them down and relieving pressure on the German 8th Army in East Prussia. By conducting offensives along the Dniester and Bug Rivers, the Austro-Hungarians could aim to stretch the Russian lines and exploit weaknesses, facilitating opportunities for German breakthroughs.

Additionally, Austria-Hungary could safeguard the southern flank of the German advance. If the Austro-Hungarian forces could successfully defend the Carpathian passes and maintain control over critical rail lines leading to the Balkans, they would secure German supply routes and ensure uninterrupted logistical support for the eastern campaign.

To align with Germany's broader strategic objectives, the Austro-Hungarian Army might also be called upon to launch diversionary attacks or feints to mislead Russian commanders about the proper focus of the offensive. This could involve concentrated pushes toward Lviv or other key cities in Galicia, drawing Russian reinforcements southward and away from the leading German thrust toward Brest-Litovsk.

The Austro-Hungarians could also contribute to the campaign's logistics by linking their rail networks with Germany's, allowing the movement of troops and supplies across the central front. This cooperation would be particularly vital given the Austro-Hungarian Empire's position as a bridge between Germany and the southeastern theater of operations.

However, the Austro-Hungarian Army's historical weaknesses, including its limited mobility, inconsistent training, and internal divisions due to the empire's multiethnic composition, would present significant challenges. To maximize their contribution, the Germans might need to allocate advisors or even attach German units to bolster the Austro-Hungarian efforts and ensure cohesion.10

In essence, the Austro-Hungarian role would be to serve as a stabilizing force on the southern and southeastern fronts, tying down Russian units and providing the Germans with the operational flexibility to concentrate their forces on achieving decisive victories in the north and central eastern theaters. The plan's success would hinge on the ability of the Austro-Hungarians to hold their ground and maintain their commitments, as any collapse of their front would threaten to unravel the entire strategy.

A Schlieffen Plan aimed at Russia would have represented Germany's high-risk, high-reward strategy, requiring exceptional coordination, swift execution, and extensive reliance on logistics and rail infrastructure. The plan's success would hinge on the ability of the German and Austro-Hungarian forces to overcome significant geographical and operational challenges, from vast distances and difficult terrain to entrenched Russian resistance. While the Austro-Hungarians played a vital role in tying down Russian forces in the south and securing critical supply routes, the core of the strategy would lie in Germany’s ability to outmaneuver and decisively cripple Russian formations, potentially forcing a political settlement or destabilizing the Russian state. However, the complexities and inherent risks of such an offensive—coupled with the formidable logistical hurdles and the possibility of Russian reinforcements—would have made this alternative Schlieffen Plan a perilous gamble, one that might have changed the course of the war had it succeeded.

The Case For the Plan

While there were no good options, there was one for the German General Staff. Staying on the defensive in the West while seeking a decisive victory in the East. The Schlieffen plan was fraught with pitfalls; the unnecessary provocation of new enemies, logistical nightmares, the potential for a swift French redeployment to counter the German flank maneuver due to interior lines, the numerical inadequacy of the German army, the tendency of the attacker’s strength to diminish with each advance while the defenders grew, and the lack of time to defeat France before Russia launched its attack.11 The German General staff knew that victory would not be reached quickly, that a direct attack from France could be defended relatively quickly, and that even with Russia's vastness and massive army, it was still a fragile force.12 The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 suggested that the Russian Bear might not be as formidable as it once appeared. Schlieffen would write in the aftermath,

The East Asian war has shown that the Russian army is less competent than had been previously assumed by informed opinion and that the war has worsened the Russian army rather than made it more efficient. It has lost all complaisance, all confidence, and all obedience. It is very questionable whether or not an improvement will take place.13

The political embarrassment of being defeated by a small nation at the end of their empire suggested that victories closer to St. Petersburg or Moscow might lead to the downfall of the Romanov Dynasty, but the German General Staff had embraced the concept of “total victory” even though its chief architect, Moltke the Elder, had dissociated himself from it many years prior.

Wargames conducted by the general staff also hinted that “total victory” was becoming out of reach. While conducting a wargame where he was in charge of the French army, Schlieffen managed to defeat his own plan with a railway maneuver that the French general Joseph Joffre would use at the battle of the Marne in the fall of 1914. In another war game centered in the East, Schlieffen used railway mobility to defeat a Russian advance around the Masurian Lakes, which mirrored the maneuver that led to the encirclement of the Russian 2nd Army at Tannenberg in August 1914. Interestingly, the General Staff conducted a simulation of a reverse Schlieffen Plan, shifting the primary focus to the east.14 However, they concluded that the French Army would quickly overwhelm the minimal forces left to defend the Rhineland long before Germany could achieve a decisive victory against Russia.

The destruction of numerous documents makes it challenging to determine whether a "reverse Schlieffen Plan" was ever seriously considered as an alternative. However, the prevailing belief within the German General Staff that France would inevitably break through into Germany reflects their own offensively oriented biases. Several wargames were run by the General Staff based on a defensive strategy in the West as an academic exercise.15 Much to their frustration, the wargames revealed that the French Army would struggle to achieve a decisive breakthrough through Alsace-Lorraine against even a modest defensive force. In later years, however, when war games using this scenario were repeated, the German defenders were assigned fewer troops, while Belgian and Dutch forces were inexplicably added to the attacking side for the sake of convenience. Additionally, the attackers were granted unrealistic advantages in mobility, disregarding the lack of infrastructure and the challenges posed by the wooded terrain. This would explain how the idea of attacking the Russian Army fell out of favor.

The notion that European armies marched off in 1914 expecting the war to be “over by Christmas” is something of a cliché, as many professional soldiers at the time were well aware of the potential for a prolonged conflict. General Ernst Köpke, the quartermaster of the general staff in 1905, assessed

Even with the most offensive spirit... nothing more can be achieved than a tedious and bloody crawling forward step by step here and there by way of an ordinary attack in siege style in order to slowly win some advantages…There are sufficient indications that future warfare will look different from the campaign in 1870–1. We cannot expect rapid and decisive victories.16

Schlieffen wrote privately in 1905, “If the enemy stands his ground...all along the line, the corps will try, as in siege-warfare, to come to grips with the enemy from position to position, day and night, advancing, digging in, advancing.”17 Even the executioner of the Schlieffen plan, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger admitted in a moment of honesty with the Kaiser that any war would almost certainly be a “long arduous struggle with a country which will not admit defeat until the strength of the people is broken.”18

Köpke, Schlieffen, and Moltke the Younger's comments reflect a keen understanding of the evolving nature of warfare in the early 20th century. Their acknowledgment of the limits of rapid, decisive victories highlights a recognition that modern conflicts, particularly those involving industrialized armies and advanced weaponry, would be characterized by attrition rather than the swift, overwhelming offensives of the past. The shift towards a "siege-warfare" mentality, as Schlieffen described it, foreshadowed the reality of trench warfare that would dominate World War I. However, this foresight was dismissed by institutional biases within the German General Staff, which clung to offensive doctrines rooted in the successes of 19th-century warfare. This wasn’t just limited to the German General Staff, almost every European Army had been infected by what political scientists Jack Snyder and Stephen Van Evra called “The Cult of the Offensive.”19 The persistent belief in rapid victories, despite evidence to the contrary, reveals a critical failure to adapt to the evolving realities of war—a failure that would have devastating consequences when the Schlieffen Plan unraveled under the weight of prolonged conflict.

Russia had also taken a crash program to build railroad infrastructure towards the German border, allowing for a speedier mobilization, deployment, and attack into East Prussia.20 While an Eastern Schlieffen plan could take advantage of this, the German General’s staff conclusion from this was to double down on attacking France because it would mean the window of opportunity to win would be shortened. Moltke wrote to the German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg of the effects:

This means that whereas now the Russian army deploys and has ready for operations half of its army on the western border by the 13th mobilization day and two-thirds by the 18th mobilization day, after the completion of the railway construction plan, [Russia will be able to deploy] two-thirds [of its army] already by the 13th mobilization day and the entire strength by the 18th mobilization day.21

The German general staff projected it would take six weeks to achieve a “total victory” against France, but a full-strength Russian army could attack East Prussia in less than three weeks. Frankly, there was no way that the German Army could achieve victory in this time frame, and yet they plunged ahead anyway.22

A crucial aspect of maintaining a defensive posture in the West would have been preventing British intervention. Although Schlieffen and the General Staff designed their plan with British involvement in mind, substantial evidence suggested that Britain was not eager to intervene on France's behalf, especially during the July Crisis. Prince Heinrich of Prussia reported on July 28, 1914 that King George V had explicitly stated the British government would “try all we can to keep out of this and shall remain neutral.”23 Three days later on August 1, German Ambassador Lichnowsky conveyed to Berlin that British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey had proposed that Britain would remain neutral and guarantee French neutrality if Germany focused its efforts in the East and refrained from attacking France.24 That same day, the British Cabinet decided against deploying the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to the Continent. As a result, Grey informed his French counterpart, Paul Cambon, that “France must take her own decision at this moment without reckoning on assistance that we are not now in a position to promise.”25 It was only when the British decided that violating Belgian neutrality was cause for going to war that intervention became 100% certain.26

Even if Britain had decided to intervene later, it would have at least given Germany time to fight in the East. As Political Scientist Scott Sagan observed,

The near victory of the German offensive in 1918 against the French, a fully mobilized and deployed British army, and the arriving Americans suggests that a massive German offensive against the French alone (or the French and the small British Expeditionary Force) would have stood a strong chance of success.27

However, this assumption would be predicated on the Germans launching their massive offensives of 1918 within France, whereas, in this case, they would have had to attack from the German border. If Germany had stood pat for more than a few months and the French had gone on the defensive, the fortifications that would have sprung up would have made the Maginot line look like child’s play. Less than a year into his tenure as Chief of the General Staff, Moltke grasped why Schlieffen had determined that a flanking maneuver through Belgium was essentially the only viable option against France. The artillery available to the German army was insufficient to break through fortified positions directly, and developing and producing the “super-heavy howitzers” required for such an effort would take years if not decades.28

This raises the question of whether an attack through Belgium and Luxembourg during 1915–1918 might have been more successful. Whenever the German Army had the chance to concentrate its forces, its offensives were typically effective.29 The challenge, however, was that Germany often had to shift its forces between different theaters, rarely achieving full concentration for a sustained effort. Alternatively, instead of attacking through Belgium, Germany could have attempted to persuade Belgium to join the Central Powers.30 History offers several examples of nations aligning with one side after hostilities began, such as the Ottomans in 1915, the Romanians in 1916, and the Americans in 1917. However, German diplomacy during the war was notably poor. If anything, their efforts might have backfired, alienating Belgium further and driving it more firmly into the Allied camp. France had initiated a crash program to rebuild defenses along the Belgian border. Had the Germans delayed their attack, they would have faced significant challenges in maintaining their momentum, even if they managed to cross Belgium swiftly, they likely would have bogged down before they could reach Paris.

The German General Staff faced a complex set of challenges in balancing the strategic imperatives of the Eastern and Western fronts. While attacking through Belgium in 1915–1918 might have offered some opportunities for success, it also carried significant risks, including prolonged attrition, logistical constraints, and provoking new enemies, the exact same problems they faced in 1914. Diplomatic alternatives, such as aligning Belgium with the Central Powers, were undermined by Germany’s inept statecraft, which often alienated potential allies. Moreover, the potential for rapid fortification of the Belgian and French borders further reduced the feasibility of achieving a decisive breakthrough. Ultimately, the General Staff’s fixation on offensive doctrines and "total victory" blinded them to the potential advantages of a more defensive posture in the West and a focused campaign in the East. This failure to adapt to the evolving realities of industrialized warfare not only squandered opportunities for a more favorable strategic outcome but also condemned Germany to a prolonged and ultimately catastrophic war.

The Case Against the Plan

There are plenty of reasons why Germany decided to take the massive risks they did. Given that Russia’s vast size and slower mobilization would give Germany valuable time to focus on France, the plan's core premise rested on the assumption that a rapid and overwhelming attack through Belgium would catch the French off guard and lead to a swift victory. Once France was defeated, Germany would then be able to redeploy its forces eastward to confront Russia, whose army would be ill-prepared for immediate combat; at least, that was the theory. History backed this logic in many ways—both Charles XII and Napoleon had seen their armies destroyed deep within Russia centuries earlier, setbacks from which they never truly recovered. The Russian Army had also undergone significant reform, and by 1910, German intelligence acknowledged this development.31 The Russians could also simply withdraw into the interior of Russia before “we would achieve the destruction of the Russian Army,” leaving Germany engaged in a “series of costly and indecisive frontal battles,” as Schlieffen described it.32 France would theoretically have much less room to maneuver, so they couldn’t avoid the “decisive” battle with which the German General Staff was obsessed with obtaining. But if we take Terence Zuber’s (very controversial) conclusion,

At no time did either Schlieffen or Moltke plan to swing the German right wing to the west of Paris. They always kept the left wing very strong, as it might well conduct the decisive battle. The war in the west would begin with a French attack. The rest of the campaign would end with the elimination of the French fortress line. It would involve several conventional battles, not one battle of encirclement. If the Germans did win a decisive victory, it would be the result of a counter-offensive, not through an invasion of France. There was no intent to destroy the French army in one immense battle.33

In Zuber’s interpretation of events, if Russia launched an offensive in the east, Germany's strategy would involve counterattacking there while maintaining a defensive posture in the west.34 Conversely, if the Russian frontier was secure, Germany would shift its focus to the west, counterattacking by maneuvering the right wing of its army behind the French fortress line while using the left wing to pin French forces in place. Both Schlieffen and Moltke anticipated that Germany would prevail by breaching the French fortress line from both the front and rear. Only after completing this initial campaign, expected to last about a month, would the German army proceed with a second campaign into the interior of France.

One of the main arguments in favor of the Schlieffen Plan was its emphasis on speed and initiative. The plan aimed to exploit Germany's superior mobilization capabilities and take advantage of the limited time available before Russia could fully mobilize. By concentrating German forces in the West and utilizing their superior logistics and railway systems, the Schlieffen Plan sought to achieve a decisive breakthrough. This quick victory in the West would not only ensure that Germany would not be bogged down by a prolonged war on two fronts but also secure the strategic flexibility to counter the Russian threat once the Western campaign had been won.

There was also no guarantee that avoiding an attack on Belgium would prevent Great Britain from intervening on behalf of the Allies. By 1905, German intelligence had already assessed that Britain could deploy up to 150,000 troops to France within weeks and hinted that they planned to do so in the event of hostilities between France and Germany.35 During the Agadir crisis in 1911, Berlin received information from London that Britain would not remain neutral in a continental conflict and would support France.36 Thus, British intervention appeared to be a question not of “if,” but of “when.” This coupled with the fact that even with all of the reforms in the Russian Army, Moltke still wrote that France was Germany's most dangerous enemy in 1911.37 Given these assessments, it was a logical decision for Schlieffen and the General Staff to design their plan under the assumption of eventual British involvement, even if significant evidence suggested otherwise.

The plan would also have hinged on strong cooperation with Austria-Hungary, which in 1914, was practically nonexistent. Very early on in his tenure, Schlieffen had actually envisioned a joint offensive with the Austrian-Hungarian Army from Silesia and Galicia into Southern Poland, but it was that lack of cooperation that always confided this plan to mere musings.38 In fact, Schlieffen regarded the alliance with Austria as a “disastrous mistake,” citing the poor quality of its army, from ineffective leadership to inadequately trained soldiers.39 Additionally, Austria’s mobilization measures, which the German General Staff considered amateurish, would have forced the German Army to align its timeline with Austria’s, rather than operating on its own schedule.

Proponents of the plan believed that it was Germany’s best opportunity to avoid a drawn-out war of attrition, which would be impossible to win given Germany’s limited resources compared to the combined strength of the Allies. Schlieffen’s strategy was designed with the understanding that the longer the war lasted, the more difficult it would be for Germany to maintain its position. Therefore, by securing a rapid and overwhelming victory against France, Germany would significantly weaken its opponents’ resolve and force them into peace negotiations. This would, in turn, prevent the kind of protracted conflict that could lead to disaster for the German Empire.

But if there was any endorsement of the Schlieffen plan’s feasibility, it was the fact that it came darn close to succeeding. The fact that the French remembered the battle as the “Miracle on the Marne” is a reflection of how much of a near-run thing the battle was. General von Kluck, who commanded the right wing, and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, commander of the German Navy, both went to their graves believing if the German attack had been initiated just a few days earlier, it would have significantly increased the likelihood of victory. Contemporary historians agree with the assessment, concluding that it would have resulted in “an overwhelming initial success” if executed in its original form.40 However, scholars such as Martin Van Creveld contend that even if Germany had secured a victory at the Marne and captured Paris, the French and British could have extended the conflict by simply refusing to negotiate, leading to a pyrrhic German success and ultimately resulting in the emergence of trench warfare anyway.41

Finally, the Schlieffen Plan had a certain logic within the context of its time. Technological advancements, such as railways, enabled the rapid movement of troops and artillery, making a swift and well-coordinated offensive seem plausible. As much as these technologies were an enabler for defensive warfare, they were also an enabler for offensive warfare. The plan was premised on the belief that such a decisive strike could shatter the enemy's will to fight before they could fully mobilize. The early successes of German military doctrine during the wars of unification bolstered confidence in the feasibility of such a strategy. While hindsight exposes its flaws, the Schlieffen Plan was, at the time, viewed as Germany's best chance to secure a quick and decisive victory, avoiding the peril of a prolonged two-front war. After all, rolling the iron dice was the way the Germans played the game since the days of Frederick the Great.

Whenever one deals with alternative history, one inevitably raises more questions than answers. It's difficult to determine in the long term how much an “eastern” Schlieffen plan would have altered the outcome of the war. Instead of a slim chance of fighting a war on two fronts, the Eastern plan guaranteed it but offered more political flexibility. The German historian Hans Delbruck would lament the decision to attack Belgium, stating that attacking Russia instead would have at least dampened the enthusiasm for British intervention.42 However, political flexibility was never in the minds of the German general staff, who believed they should have the most say in the strategy of war. If staying on the defense in the West kept Britain out of war, Germany would have won. Even if Britain had intervened later, there is still a strong possibility that they would have won outright or at least brought the war to an end on favorable conditions. It was only when the United States sided with the Allies three years into the conflict that a German defeat was sealed.

An eastern Schlieffen Plan focused on a rapid and decisive offensive against Russia, would have required a delicate balance of swift execution, superior logistics, and coordination between German and Austro-Hungarian forces. By concentrating on crippling Russia’s military and logistical capabilities, mainly targeting key strategic locations like Brest-Litovsk and Warsaw, Germany could have potentially forced a political settlement or destabilized the Tsarist regime, thereby shortening the war. However, the vast distances, harsh terrain, and Russia’s formidable resistance posed significant challenges to the success of such a strategy. While the Austro-Hungarian Army played a critical supporting role, their weaknesses would have added further complexity. This high-risk, high-reward approach could have dramatically altered the course of the war, but its success was far from assured, making it the same precarious gamble Germany undertook when it decided to violate Belgium’s neutrality.

Ultimately, the German General Staff’s rigid adherence to the Schlieffen Plan sealed its fate—and that of the entire war. By clinging to outdated concepts of offensive warfare and underestimating the defensive potential of their enemies, the Germans were doomed to repeat the very mistakes they sought to avoid. A shift in strategy, favoring a defensive posture in the West while focusing efforts on the East, could have offered a more sustainable path to victory, preserving precious resources and buying time against the overwhelming tide of industrialized warfare. But with the obsession for “total victory” and the blind spots created by wargames, miscalculations, and diplomatic blunders, Germany’s chance to break the deadlock was squandered. In the end, what could have been a more decisive and calculated campaign instead unfolded into a brutal, attritional struggle, forever altering the course of the 20th century.

References

Evera, Stephen Van. 1984. "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War." International Security, Vol. 9, No. 1 58-107.

Foley, Robert T. 2006. “The Real Schlieffen Plan.” War in History 13, no. 1: 91–115.

Forster, Stig. 1990. “Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914,” in Manfred F. Boemeke, Roger Chickering, and Forster, eds., Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 Washington, D.C.: German Historical Institute.

Kissinger, Henry. 1995. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lieber, Keir A. 2007. “The New History of World War I and What It Means for International Relations Theory.” International Security 32, no. 2: 155–191.

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. 1986. "Détente and Deterrence: Anglo-German Relations, 1911-1914." International Security, Vol. 11, No. 2 121-150.

MacMillan, Margaret. 2014. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. New York: Random House.

Papayoanou, Paul A. 1996. “Interdependence, Institutions, and the Balance of Power: Britain, Germany, and World War I.” International Security 20, no. 4 42–76.

Ritter, Gerhard. 1958. The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth. London, W.i.: Oswald Wolff.

Sagan, Scott D. 1986. “1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability.” International Security 11, no. 2: 151–75.

Snyder, Jack. 1984. "Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984." International Security 9 (1) 108-146.

Zuber, Terry. 2011. The Real German War Plan 1904–14. Stroud: The History Press.

Zuber, Terry. 2002. “The Schlieffen Plan: Fantasy or Catastrophe?” History Today, Vol. 52: 40-46.

See Stacie E. Goddard, "When Right Makes Might: How Prussia Overturned the European Balance of Power." International Security 33 (3) (2009): 110-142.

Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (New York: Random House, 2014), 339.

Schlieffen essentially decided on the basic principles of this plan, an attack against France in August 1892. Gerhard Ritter, The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth (London: Oswald Wolff, 1958), 40.

Jack Snyder, "Civil-Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984" International Security 9 (1) (1984): 116.

For the standard treatment and original documents, see Gerhard Ritter, The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth (London, W.i.: Oswald Wolff, 1958). For more recent research, see David T. Zabecki, The Schlieffen Plan: International Perspectives (University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster. 1995.), 205.

Terry Zuber, The Real German War Plan 1904–14. (Stroud: The History Press, 2011), 54-57.

For more on the Schlieffen Plan, see Zabecki, David T. The Schlieffen Plan: International Perspectives on the German Strategy for World War I, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

Robert T. Foley, “The Real Schlieffen Plan.” War in History 13, no. 1 (2006): 108.

German Units were attached to the Austrian Hungary in every major campaign after 1914.

Snyder, 116-117.

However, in a 1912 wargame based on this scenario, it was determined that by around the 45-day mark, the French would capture the fortress city of Metz and be positioned to break through into the German heartland, while no decisive outcome had been achieved on the Eastern Front. It is difficult to determine the extent to which the wargame was influenced by the offensive biases prevalent in many simulations of the time.

Quoted in Foley, 99.

Snyder, 117.

Snyder, 117

Quoted from Förster, “Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914,” 355-356.

Quoted in, Gerhard Ritter, The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth (London, W.i.: Oswald Wolff, 1958), 144.

Quoted from Ritter, 138.

The “Cult of the Offensive” is a term that rose to prominence in the 1980s and refers to a military doctrine and mindset prevalent among European military leaders before and during World War I, which emphasized the strategic advantage of offensive operations over defensive ones. This belief was rooted in a misreading of Clausewitz that led to the assumption that rapid and aggressive attacks would lead to quick and decisive victories, thereby preventing prolonged and costly wars. The doctrine influenced military planning and led to the development of strategies that prioritized offensive maneuvers, often at the expense of any defensive considerations. It was a strange development that as the offensive became more entrenched, technological developments increasingly made the defense the favorite.

Foley, 107.

Quoted from Foley, 108.

Sure enough, German troops were transferred from the West to the East when the Russian attack began in late August 1914.

Scott D. Sagan “1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability.” International Security 11, no. 2: (1986): 168.

Sagan, 167.

Quoted in Paul A. Papayoanou, “Interdependence, Institutions, and the Balance of Power: Britain, Germany, and World War I.” International Security 20, no. 4 (1996): 65.

Papayoanou, 65.

Sagan, 162.

The largest German gun available in 1906 was capable of penetrating 1 meter of armor, while the rebuilding of the French fortresses had given each fort a covering of 3 meters. Foley, 109.

For example, the massive German offensives in 1914 and 1918 were very successful. Whenever the German Army took to the offense in the East in large numbers, there were usually breakthroughs.

German diplomacy towards Belgium in the leadup to the war consisted of lobbing threats and other hostile actions. Ritter, 116.

Foley, 107.

Foley, 108.

Terence Zuber, “The Schlieffen Plan: Fantasy or Catastrophe?” History Today, Vol. 52 (2002): 46.

Zuber published his core claims in Terence Zuber, "The Schlieffen Plan Revisited" History Today Vol. 6, No. 3 (July 1999), 262-305. Zuber argues that there was no true "Schlieffen Plan," suggesting instead that Schlieffen’s 1905 memorandum was not a strategic blueprint for future German military deployments. Instead, Zuber claims it was an elaborate attempt by Schlieffen to secure more troops from a hesitant Ministry of War. This has spawned a host of rebuttals and counters over the years.

Ritter, 29.

Ritter, 84.

Keir A. Lieber, “The New History of World War I and What It Means for International Relations Theory.” International Security 32, no. 2: (2007): 185. Bethmann Hollweg dismissed the situation, stating that it was "not actually that serious" and only reaffirmed what had long been known: that England still pursued a policy of balance of power and would thus support France. Similarly, the Kaiser insisted, "We have always reckoned on the English as our probable enemies."

Ritter, 30.

Ritter, 29.

Gordon A. Craig, The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640-1945 (London: Oxford University Press, 1955), 280 and Walter Goerlitz, History of the German General Staff (New York: Praeger 1953), 135.

Martin Van Creveld, Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 116.

Zuber, “The Schlieffen Plan: Fantasy or Catastrophe?” 40.

This is stonkingly great work mate, well done! I absolutely adore First World War history - the ultimate steampunk experience (my favourite anecdote is that of British submariners surfacing to then BOARD an enemy vessel...with CUTLASSES), and still very relevant to our present day.

1914 is almost mythical in its scope, which I think you have captured well - so many conflicting viewpoints of one of the most interesting points in European history. I'm not sure where I am with the Schlieffen Plan; potentially doomed from the start but the least-bad out of several crap options for Germany. A two-front war was never going to go well, and the fact that the Germans came very close to clinching it on several occasions - even up to the end of the war - is frankly testament to the sheer survivability of the industrial nation state and the capacity of the German military machine. While I agree that American involvement in the end (sheer reserves of fresh, if inexperienced, manpower) probably was the straw that broke the camel's back in 1918 (especially following the Spring Offensive), I would also note the crippling blockade enforced by the Royal Navy. Germany was literally at the point of starvation by the end of the war, often forgotten in the popular imagination.

Also recall the disastrous French offensive (Plan 19) against the German frontier in 1914. Massive casualties for the French army with almost no gain in territory. Not only could the Germans hold the French off in the West but in the actual event they did.