Ukrainian Abwehrschlacht: Defense in Depth in Modern Warfare

Dispatches from the Frontline and Lessons Learned

The higher command should not make it a rigid and unconditional rule that the ground cannot be abandoned. It should conduct the defense so that its own troops are on favorable ground, while the attacking force is only left unfavorable ground. Therefore, the armies and army corps are to ensure that orders for the evacuation of sectors are given when the situation no longer requires they be held.1 - German Defensive Manual, 1917

War has always been a brutal test of adaptation. The armies that survive are those that learn, adjust, and innovate faster than their enemies. Nowhere is this more evident than on the battlefields of Ukraine, where a new generation of officers is reshaping how the war is fought. Among them is “Andriy,” a battalion commander who, like many of his peers, has rejected outdated doctrines in favor of a more flexible, layered defense. Drawing from both historical lessons and the realities of modern warfare, he has implemented a defense-in-depth strategy designed to wear down Russian forces long before they can achieve a decisive breakthrough. His approach reflects a broader shift within the Ukrainian Armed Forces—one that is grinding down the Russian war machine at an unprecedented rate.

The German Army in World War I was the first military to introduce the concept of defense in depth. The apocalyptic battles at Verdun and the Somme in 1916 had pushed the German Army in the Western Front to the breaking point; 147 Divisions had seen action in the Somme, suffering some 430,000 casualties.2 So many units seeing action had produced a huge number of Erfahrungsberichte (lessons-learned reports). Divisions found they could no longer spend a maximum of two weeks on the front line at the Somme, and there was a noticeable difference in combat proficiency.3 They also found that the frontline trench was becoming increasingly useless as artillery became more accurate and sustained. British and French aircraft also controlled the skies over the Somme for most of the battle. This air dominance allowed them to closely observe German movements and logistics behind the front line.4 The 22nd Reserve Division observed:

Enemy aircraft possessed unlimited command of the air. With extraordinary daring, they overflew our infantry and artillery positions at very low heights (200 to 300 meters), in all weather, even rain, taking no notice of infantry fire, took their photographs, and directed the fire of their artillery.5

The under constant aerial observation and the need for constant counterattacks left units vulnerable to artillery fire and took them away from where they were actually needed, relieving units on the frontline. At the same time, the High Command of the German Army also realized that there needed to be systemic tactical changes.6 The general staff had already begun work on a defensive manual in September 1916 in the last stages of the battle of the Somme.7 By January 1917, the manual was being circulated among senior commanders on the Western Front. There was skepticism among some commanders as the manual called on division commanders to take more control of the situation, and thus, corps and army commanders would lose influence.

Two of the primary opponents to the concept of elastic defense were Fritz von Below and Colonel Fritz von Loßberg.8 As the commander and chief of staff of the German First Army—one of the most heavily engaged forces during the Battle of the Somme—they had firsthand experience with large-scale defensive battles. Their insights carried significant weight, and as a result, the German High Command circulated their after-action report in January 1917. While much of their analysis aligned with the principles outlined in the Defensive Battle doctrine, a key point of contention emerged regarding temporary withdrawals from the front line. In direct contradiction to the evolving concept of elastic defense, the First Army reaffirmed its earlier Somme directive; defenders were to hold their positions at all costs, even if it meant fighting to the death. This stance was further reinforced in the new infantry training regulations issued in February 1917, which explicitly mandated that infantry squads were to hold out to the last man.9

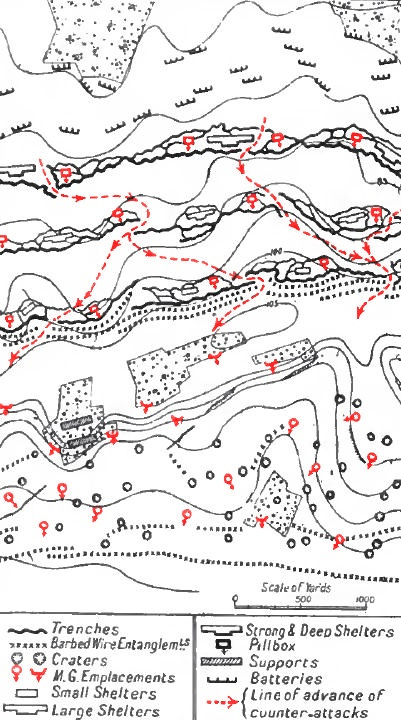

Nonetheless, Erich Ludendorff had taken over as First Quartermaster-General after his highly successful campaigns in the East and political maneuvering. Under his command, the army plowed ahead with Abwehrschlacht, “defensive battle.” This strategy replaced static trench lines with a series of defensive zones spread across several kilometers. The first zone, or "outpost zone," was lightly held and designed to slow and disrupt enemy advances. Behind it lay the "battle zone," the primary defensive position where most of the German firepower, including machine guns and artillery, was concentrated. Further back was the "rearward zone," a fallback position to contain any breakthroughs.

Key features of this system included fortified strongpoints, well-camouflaged machine-gun nests, and pre-registered artillery targets, all designed to maximize the effectiveness of defensive firepower. The strongpoints were heavily fortified positions that could hold out against prolonged assaults, acting as anchors for the defense. These positions were interconnected by concealed communication trenches and supported by carefully positioned machine-gun nests, which were often concrete bunkers camouflaged to blend seamlessly into the terrain. This camouflage not only reduced the risk of detection but also allowed the defenders to deliver devastating enfilading fire against advancing enemy troops.

Pre-registered artillery targets were another critical component because communication with soldiers in the frontline trenches was bound to be cut as soon as they came under sustained bombardment. Pre-registered fire zones allowed German artillery units to deliver accurate and immediate fire on advancing enemy formations. These artillery barrages were coordinated to break up attacks, disrupt supply lines, and inflict heavy casualties on exposed troops. By focusing fire on predetermined areas, the Germans minimized the time needed to adjust their guns, enhancing their ability to respond quickly to shifting battle conditions.

The Germans also implemented an elastic defense strategy as part of this system. Instead of rigidly holding the frontline at all costs, frontline troops were instructed to give up ground when under heavy pressure. This deliberate withdrawal was not a sign of defeat but a tactical decision to draw the enemy into vulnerable positions. As attackers advanced into these areas, they were exposed to concentrated artillery and machine-gun fire from the battle zone further back. Once the enemy's momentum had been slowed or halted, German reserve forces were deployed to launch counterattacks, often restoring the original positions or even driving the attackers back.

This layered defensive strategy allowed the Germans to conserve manpower while maintaining operational effectiveness. Between September 1916 and July 1917, it enabled the expansion of the army to 175 divisions, the return of 125,000 skilled workers to the war economy, and the exemption of 800,000 workers from conscription.10 By focusing on inflicting maximum casualties on the enemy and minimizing the heavy losses typically associated with static trench warfare, this system proved highly effective. It reached its pinnacle along the Hindenburg Line, where the Germans integrated these tactics into a complex network of bunkers, tunnels, and barbed-wire defenses. This formidable system not only bolstered the line’s defensive strength but also served as a testing ground for the principles of defense in depth, leaving a lasting impact on military strategy in the years that followed.

The Ukrainian Military faces many of the same challenges that the German Army encountered in late 1916—most notably, a dwindling manpower pool and relentless offensive pressure from a determined adversary. Just as Germany, after months of brutal fighting at Verdun and the Somme, found itself struggling to replenish its ranks while maintaining a coherent defensive line, Ukraine is grappling with the exhaustion of its frontline troops and the logistical strain of sustaining a prolonged war of attrition. Casualties, recruitment difficulties, and the physical and psychological toll of continuous combat have placed increasing pressure on Ukrainian forces, much as they did on German divisions that had been rotated in and out of the Somme and Verdun battlefields with limited time for recuperation.

Moreover, Ukraine—like Germany in 1916—faces an enemy with superior numerical reserves, forcing it to rely on defensive innovation, force conservation, and asymmetric advantages rather than sheer manpower. The introduction of more flexible defense-in-depth strategies, reliance on precision firepower, and integration of modern technology such as drones and Western-supplied long-range artillery echoes Germany’s transition from rigid trench lines to an elastic defensive system designed to absorb and wear down enemy assaults.

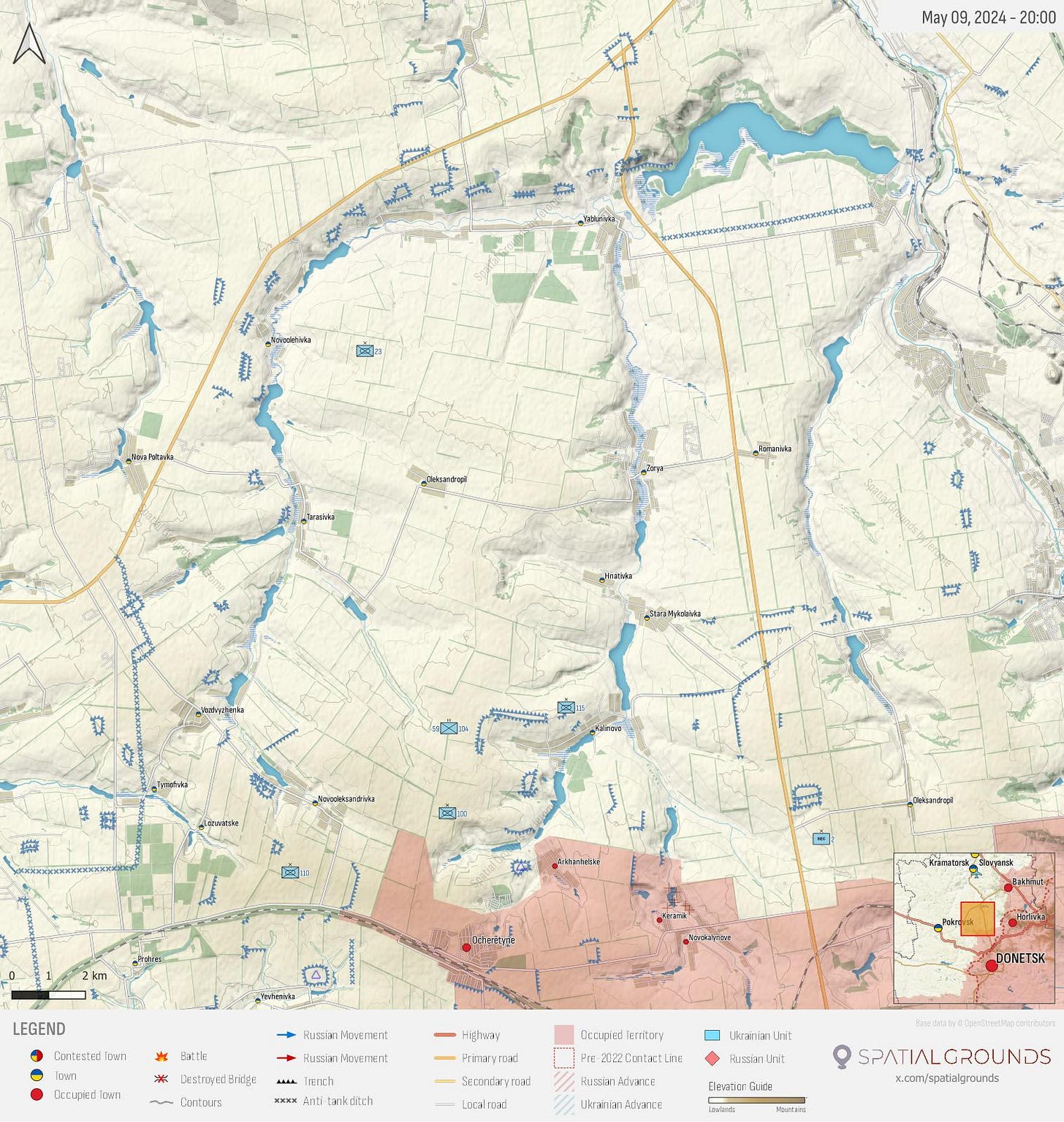

Ukrainian defensive doctrine still varies significantly from unit to unit, reflecting the decentralized and adaptive nature of the UAF.11 Unlike a rigid, top-down structure, units often tailor their defensive strategies based on terrain, available resources, and operational needs, leading to a mix of traditional trench-based defenses, mobile elastic defense tactics, and technologically integrated approaches that emphasize drones and precision artillery.

However, some commanders have insisted on holding all ground, no matter the cost. For example, in October of 2024, the 210th Battalion of the 59th Motorized Brigade was in heavy combat near Pokrovsk and requested to withdraw, believing they were in poorly defensible positions and suffering casualties without purpose.12 In response, commanders from the 110th Mechanized Brigade allegedly issued threats against the 210th Battalion, warning of severe disciplinary actions—or even execution—if they abandoned their positions. With no direct artillery, mortar, or armored support from the 110th, the battalion decided to withdraw and was later accused of cowardice, with some soldiers allegedly being detained. This variability is in part due to the historical legacy of Ukraine’s pre-2022 military structure, which relied on Soviet-style brigade-level formations and Tactical Groups rather than larger, more autonomous corps.

It was only recently that the UAF began implementing a corps system across the board, seeking to create a more structured, higher-level command framework capable of coordinating multi-brigade operations and improving logistics, planning, and battlefield sustainability.13 This transition is still ongoing, and as a result, some units operate with a fair amount of autonomy, while others have begun integrating into larger corps structures, particularly in areas where offensive and defensive operations require extensive coordination over vast frontlines. The gradual shift toward a Western-style corps structure is intended to enhance Ukraine’s ability to conduct large-scale, multi-domain operations, but for now, defensive doctrines remain diverse, reflecting both necessity and battlefield realities.

“Andriy” graduated from the Academy of Ground Forces in 2016.14 He spent time in the Donetsk Oblast, where he witnessed the Cold War-style trench warfare that had defined the conflict in previous years since the war began in 2014.15 When the full-scale invasion began, he was serving in a staff position within the intelligence section of Ground Forces Command in Kyiv.16 Over the past three years, Andriy has gained diverse experience. He remained in his staff role through the summer before volunteering for the infantry, assuming command of a company in one of the newly mobilized brigades participating in the Battle of Bakhmut.17 In the late winter of 2024, he was promoted to deputy commander of a mechanized battalion. By summer, he had assumed command of his own battalion.

Andriy had long considered the merits of a defense in depth strategy, growing increasingly frustrated with senior command’s insistence on holding every position at all costs.18 He saw this approach as wasteful and unsustainable, needlessly sacrificing troops and equipment. Nowhere was this more evident than in Bakhmut and Avdiivka, where the battles had devolved into relentless vortexes, consuming manpower and resources at an alarming rate. While he understood the political rationale behind maintaining control of territory, he believed the army had overextended itself in the effort. In his view, the rigid defense of every position and the "front-loading" of forces along the line of contact left infantry—especially inexperienced troops—highly vulnerable to Russian artillery, loitering munitions, and drone strikes.19 These risks were further compounded by the shortage of combat engineers and construction equipment, limiting the ability to fortify positions or build fallback defenses.

When Andriy assumed command, his battalion was typical of the summer of 2024, short on personnel, equipment, and experience. However, he did have quality armor donated by NATO countries with battle-hardened crews, experienced drone operators, and a manageable supply of artillery. His battalion, composed of 440 men built around three mechanized companies, along with supporting companies and platoons—including anti-tank, mortar, and reconnaissance units—was responsible for defending approximately 5 kilometers (just over 3 miles) of the frontline.20

Russian assault tactics over the last 12-18 months or less rely on a methodical, attritional approach, using poorly trained volunteers to probe defenses before committing to more significant offensives. Their strategy unfolds in distinct phases as described by the Royal United Services Institute in a recent report:

Russian units, upon entering the line, tend to conduct wide-ranging advances to contact in section strength, endeavoring to identify Ukrainian positions. First, they send sections/squads of poorly trained troops, perhaps eight personnel at a time (although some larger attacks consist of up to 30 personnel supported by one or two infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs)). These are ordered to advance towards where they assess Ukrainian positions to be, conducting reconnaissance by drawing fire. If the group encounters resistance, Russian commanders assess where they believe the best lines of approach are, and in particular, where the boundaries between defensive units lie. If Ukrainian positions are positively identified, sections are persistently sent forward to attack positions, which are further mapped and then targeted with artillery, FPVs and UMPK glide bombs. When rotation or disruption of the defense is achieved, Russian units aim to conduct more deliberate assault actions.21

Whereas British strategy relied on reconnaissance with airplanes, bombardment, and then attack, the Russians reverse the sequence, opting for attacking in small assault teams, reconnaissance with drones, and then bombardment with artillery and loitering munitions—a method that results in heavy casualties among its poorly trained volunteers but allows them to identify and map Ukrainian positions through direct engagement. A battalion commander in the National Police described how in the city of Toretsk; the Russian army would send two soldiers forward to a suspected Ukrainian position with a drone following overhead. As soon as they take contact, the position is identified and bombarded with mortars. A truly crude strategy, but effective.

To counter these tactics, Andriy abandoned the concept of a traditional "front line" in favor of a mobile, flexible defense that engaged the enemy broadly across the battlefield.22 This served a dual purpose: to wear down Russian advances long before they could achieve a decisive breakthrough and to disperse his troops over a wide area so they could not be targeted with firepower. He wanted to draw the Russians as far away from their lines as possible whilst also using indirect fire to break up larger assaults before they could even get underway. The area further back was fortified with mines, barbed wire, and whatever obstacles the battalion could muster along obvious axes of advance, serving as the barrier to slow, disrupt, and funnel enemy assaults into kill zones where his infantry could be concentrated. The goal was not to hold ground indefinitely but to bleed the attackers and force them into predictable patterns of movement.

One of the most important weapons at his disposal were mini excavators bought via donations. Small enough to work in thick tree lines and capable of moving 8 to 12 cubic yards of soil per hour—equivalent to approximately 64 to 96 cubic yards in an eight-hour workday—this far surpasses the 1/3 to 1/2 cubic yard per hour that a human can manage.23 Instead of having one line with extensive fortifications, “Andriy” wanted multiple lines of fortifications and dugouts that would act as the both a fallback line and “main” line of resistance well behind the area of contact while also providing comfort and protection for his men. This area stretched several kilometers in length.

The initial layer of resistance, referred to as the “deep screen,” was manned by teams of machine gunners, snipers, and rifle squads armed with handheld anti-tank weapons. Numbering anywhere from 3 to 6 men, their job was to inflict maximum casualties on the enemy while avoiding protracted engagements. Occupying favorable terrain several kilometers directly in front of the “frontline,” these teams operated on a simple directive: infiltrate, engage, withdraw, and re-engage on their own terms. ISR from Russian drones limited these teams to tree lines, buildings, or other terrain with favorable concealment from above. Once under heavy pressure, they would be swiftly extracted by vehicles—often under the cover of suppressive artillery and mortar fire—and transported back to the main defensive line. Pre-arranged artillery and mortar barrages would cover their withdrawal, ensuring that the enemy could not follow them in an organized manner. Under the cover of darkness, new teams would move forward, reoccupying any positions not taken by Russian assault units and repeating the process the next day. The intention was to make every advance costly, forcing the enemy to expend considerable resources and manpower for minimal gains.

Drones are the workhorses of this strategy.24 While videos circulated on social media often showcase drone strikes with near-perfect accuracy, the reality is far different. In Andriy’s experience, drone strikes were only about 35% effective, and their impact depends heavily on weather, electronic warfare conditions, and the availability of experienced operators. This coincides with research by Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds at the Royal United Services Institute, who found that First Person View drones (FPVs) only hit their target 20-40% of the time.25 If given a choice between artillery, mortars, or drones, he would always choose artillery—its destructive power, range, and reliability made it the backbone of the battalion’s defensive strategy.26 However, this tactic cuts both ways. Since Russian forces attack in smaller numbers and vehicles rarely move in large numbers, artillery effectiveness is inherently limited, as large-scale barrages are less impactful against dispersed targets. This challenge is further compounded by the fact that his brigade operates older Soviet-era artillery systems, lacking digital fire control computers and other modern targeting technologies that enhance accuracy and efficiency in contemporary artillery platforms.

Andriy’s battalion maintained a strict priority list for fire missions, with pre-registered kill zones mapped out across the area. If Russian forces massed for an assault, they would be met with whatever indirect fire is available, forcing them to either retreat or advance in a disorganized state. Mortars provided rapid, responsive firepower while drones assisted with target identification, allowing the gunners to refine their fire. The goal was not just to kill enemy soldiers but to break up their cohesion before they could even reach Ukrainian positions.

When Andriy first implemented his strategy, the results were far from ideal.27 The transition from static defense to elastic, in-depth defense required a shift in mindset, and not all of his troops adapted quickly. Some of the forward teams, upon hearing gunfire nearby, misjudged the situation and withdrew prematurely, abandoning their positions without coming under direct attack. Others, determined to hold their ground at all costs, hesitated to retreat even when their flanks were compromised and under bombardment, leading to unnecessary losses and allowing a substantial group of Russian forces to reach the main line of resistance far quicker than he had anticipated.

The failure of the initial execution left Andriy with a difficult choice. He could either accept the setback, withdraw entirely to the main defensive line, and rework the plan—or he could launch a counterattack to restore the integrity of the defense and refine the strategy in real time. He chose the latter, committing his armored vehicles and reserve companies to an intense, close-quarters engagement.

For hours, his troops waged a brutal battle to clear out the Russian forces, employing a combination of mechanized assaults, indirect fire, and close-quarters infantry engagements. “The biggest challenge in these situations,” Andriy stated, “Is not being an armchair general.”28 The proliferation of mass surveillance and reconnaissance via drones allowed him to watch the battle unfold in real time, and the temptation to micromanage was strong. But he knew success depended on trusting his troops on the ground to assess the situation and adapt as needed.29

The Russians, having overextended themselves, were caught off guard by the ferocity of the counterattack. Ukrainian artillery, pre-registered on likely Russian staging areas, hammered retreating troops, while Andriy’s armor units spearheaded a push that forced the enemy back. By the time the fighting subsided, the line had been restored, the wounded evacuated, and the defense stabilized. In many ways, he had done the exact opposite of what he envisioned. His unit suffered more casualties than he had hoped, but the counterattack proved a necessary learning experience. It reinforced the importance of discipline in executing the withdrawal-and-reengagement cycle and demonstrated that aggressive counterattacks had their place even in an elastic defense.

Following the initial setback, Andriy conducted a series of after-action reviews to pinpoint weaknesses and refine the battalion’s defensive approach.30 Every engagement was analyzed in meticulous detail, from the initial contact with Russian forces to the final withdrawal or counterattack. Junior officers and enlisted men alike were encouraged to provide input, ensuring that lessons were drawn not only from command-level observations but from those directly engaged in combat. One of the most critical takeaways was the need to instill discipline in executing planned withdrawals—pulling back at the right time was just as crucial as standing and fighting. Andriy emphasized to his men that the goal was not to hold ground in a conventional sense but to dictate the terms of engagement, forcing Russian troops into predictable patterns that could be exploited.

To address the confusion that had led to unnecessary losses, forward teams underwent additional training to distinguish between incidental gunfire—such as sporadic shots or nearby skirmishes—and actual sustained pressure from an advancing enemy force.31 They practiced identifying key indicators of an imminent Russian assault, such as concentrated drone activity, artillery barrages, or coordinated infantry movements. More precise withdrawal signals were developed and standardized to avoid misinterpretation in the heat of battle. Soldiers were drilled on multiple extraction scenarios, ensuring they could seamlessly disengage under the cover of suppressive artillery and drone strikes without creating panic or disorder. Vehicles were pre-positioned in concealed locations, ready to extract teams at a moment’s notice, further reducing the likelihood of unnecessary casualties.

At the same time, Andriy placed greater emphasis on deception tactics, recognizing that psychological warfare and battlefield misdirection were just as important as direct combat engagements.32 Dummy positions were constructed using logs, scrap metal, and camouflage netting to mimic defensive fortifications, luring Russian artillery and glider bombs away from actual strong points. Some positions even had portable generators and radio transmitters to give the illusion of activity, further misleading Russian reconnaissance efforts. To add another layer of misdirection, false radio transmissions were deliberately broadcast, feeding the enemy misinformation about Ukrainian troop movements and defensive weak points. This strategy often led Russian forces to launch costly assaults on areas that were either unoccupied or only lightly defended.

In addition to these measures, Andriy integrated mobile drone teams with his forward elements, providing real-time targeting data to artillery, mortar, and drone units. This innovation significantly increased the accuracy and lethality of indirect fire. Russian troops that advanced into contested areas found themselves walking into pre-registered kill zones, where firepower in the rear could strike with precision. The synergy between drone reconnaissance and traditional artillery allowed Andriy’s battalion to inflict severe losses without exposing his troops to unnecessary risk.

With each engagement, Andriy’s battalion grew more proficient. Russian forces, expecting to steamroll through static Ukrainian positions, found themselves repeatedly drawn into elaborate ambushes. Artillery and drone-guided strikes devastated Russian advances, stalling their offensives before they could gain momentum.33 Andriy’s command philosophy revolved around one key principle: attrition on favorable terms. By limiting the number of direct firefights, his battalion could avoid excessive casualties while maximizing Russian losses. He estimated that nearly 65% of the enemy casualties they inflicted came from artillery, mortars, and drones—almost half of those from drones alone.34

This shift in tactics had a profound impact. The battalion, once plagued by personnel and experience shortages, had transformed into a hardened defensive force that could dictate the pace of battle. New troops who joined were immediately integrated into an adaptive system that relied on agility, deception, and overwhelming firepower rather than brute-force engagements. The Russians, despite their numerical advantage, found themselves unable to make meaningful progress, as every attack cost them more than they could afford to lose.35 Andriy’s success was not an isolated case—his methods reflect a broader shift within the Ukrainian Armed Forces, where younger officers are spearheading tactical innovations that are reshaping the battlefield.

This strategy is still not without challenges. Such a strategy requires constant rotation at the frontlines. The movement of troops to avoid bombardment also makes it challenging to build prepared positions, especially for fire teams deployed forward. Constant coordination with neighboring units is required as Russian forces seek to exploit the seams where one battalion’s sector meets another. While Andriy’s brigade generally operates as a cohesive unit, Ukrainian forces often consist of a mix of battalion tactical groups under one brigade command. This underscores the urgent need for the widespread adoption of the corps system across the front by the summer of 2025.36 This system will help better manage a wider potion of the battlefield and flow of reserves. With Russian forces likely to renew their offensive in one or more of the salients they carved out in 2024, a more structured and coordinated approach will be critical.

The most dangerous and vulnerable time for attack is when units are being rotated. Some Ukrainian brigades report that around 50% of their casualties occur in rear areas due to Russian FPV drones, artillery, and glide bomb strikes.37 As a result, most movement is done under cover of darkness or early morning. While casualties overall have decreased with this new strategy, the number of casualties among soldiers under the age of 30 has actually increased. “The old guys don’t do stupid shit, even when they are required to do so” he remarked.38 To help address this issue, the defense ministry has launched a new program to attract volunteer recruits aged 18 to 24, offering a range of incentives, including a Hr 1 million ($24,000) annual salary, 0% interest mortgage rates, and free higher education.39 Drone production also continues to increase exponentially. Ukraine is set to produce between 2.5 and 3 million military-use drones in 2025—and that number could go even higher, according to Ukrainian defense officials.40

Nonetheless, what had once been a defensive posture of necessity was now a deliberate strategy—one that was slowly grinding down the Russian war effort, one engagement at a time. In 2024, Russian forces endured their highest losses since the start of the full-scale war, with total military casualties reaching 434,000, including approximately 150,000 killed in combat.41 Russian forces also lost 1,400 main battle tanks and over 3,700 infantry fighting vehicles and armored personnel carriers.42 Meanwhile, its total production and refurbishment of such vehicles amounted to just 4,300, falling short of fully compensating for its battlefield losses.43 Videos circulating on social media show a Russian army that is increasingly relying on horses and donkeys for logistics. As Ukraine’s evolving defensive strategy continued to exact a devastating toll, the cracks in Russia’s war machine became ever more apparent—what was once a modern mechanized force was now resorting to tactics reminiscent of a bygone era, a stark testament to the unsustainable nature of its losses.

Ukraine’s war effort is not just a struggle for territory but a contest of adaptation and resilience. Andriy and other young officers have embraced the hard lessons of combat, forging a strategy that maximizes firepower while preserving manpower. Their ability to innovate, combined with Ukraine’s growing reliance on artillery, drones, and deception tactics, has dramatically increased Russian casualties. Yet this strategy comes with its own set of challenges, requiring continuous rotation, fresh recruits, and a level of tactical discipline that must be constantly reinforced. Still, the impact is undeniable. As Ukraine refines its defensive operations, Russia has suffered its highest casualty rates of the war in recent months. If the past is any indicator, those who learn the fastest shape the future—and on Ukraine’s evolving battlefield, the advantage increasingly belongs to those willing to rethink the way war is fought.

References

Cowan, Tony. 2019. "The Introduction of New German Defensive Tactics in 1916-1917", British Journal for Military History 5.2, 81-99.

Feldman, G. D. 1966. Army, Industry and Labor in Germany 1914–1918 Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Foley, Robert T. 2011. "Learning War’s Lessons: The German Army and the Battle of the Somme 1916." Journal of Military History 75 #2 471-504.

Foley, Robert T. 2005. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870-1916. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, G.J. 2006. A World Undone: The Story of the Great War 1914-1918. New York: Bantam Books.

Watling, Jack and Nick Reynolds, February 14, 2025. “Tactical Developments During the Third Year of the Russo–Ukrainian War,” Royal United Services Institute.

Quoted from Robert T. Foley, "Learning War’s Lessons: The German Army and the Battle of the Somme 1916." Journal of Military History 75 #2 (2011): 502.

Foley, Learning War’s Lessons, 472.

Foley, Learning War’s Lessons, 486.

Foley, 493.

Quoted from Foley, 493.

Tony Cowan, "The Introduction of New German Defensive Tactics in 1916-1917", British Journal for Military History 5.2, (2019): 81-99.

Ibid., 85.

Ibid., 88.

Ibid., 88.

G. D. Feldman, Army, Industry and Labor in Germany 1914–1918 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966), 301.

Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Tactical Developments During the Third Year of the Russo–Ukrainian War,” Royal United Services Institute (February 14, 2025), 9.

“Abandoned on the Frontline: Inside the 210th Battalion’s Struggle,” MilitaryLand Net, October 26, 2024.

Yuri Zoria, “Commander-in-chief announces major reorganization of Ukrainian military structure.” Euromaidan Press. March 2, 2025.

This section is based on text exchanges via Signal from September 2024 to March 2025. For operational security purposes and in line with the Ukrainian Army’s policy of not disclosing soldier names, he is given a pseudonym, and the unit/location are left unnamed.

Text exchange via signal, November 30, 2024.

Ibid,.

Text exchange via signal, December 4, 2024.

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Text exchange via signal, December 4, 2024.

Text exchange via signal, December 4, 2024. He also had a Special Forces platoon on loan for a few weeks.

Watling and Reynolds, 8.

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Andriy has his excavator team and combat engineers working around the clock, fuel and sleep permitting.

For more details on the role of drones, see Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Mass Precision Strike: Designing UAV Complexes for Land Forces” Royal United Services Institute. April 11, 2024.

Watling and Reynolds, 10.

Text exchange via signal, December 10, 2024. The battle occurred in early October 2024. One of the main reasons for such a high proportion of kills being caused by FPVs is the relative lack of artillery in Ukrainian units (Watling and Reynolds, 11).

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Text exchange via signal, January 7, 2025.

Text exchange via signal, February 22, 2025.

Watling and Reynolds characterize this strategy as “Attrition in Depth,” which I think is a good term (10-12).

Text exchange via signal, March 1, 2025.

There is still a lot of debate among analysts about how well Russia is recruiting and their overall manpower situation in 2025. See The Bears Will – How Has The Russian Army Stayed In The Fight?, Combat losses and manpower challenges underscore the importance of ‘mass’ in Ukraine, and Russia’s Year of Truth: The Soldier Shortage for analysis.

Corps commanders have already been appointed. “The General Staff Appoints Army Corps Commanders,” MilitaryLand Net, February 23, 2025.

Watling and Reynolds, 17.

Text exchange via signal, March 1, 2025.

Dmytro Basmat, “Over 10,000 applications to join military submitted by young recruits following introduction of 'special contracts,' Defense Ministry says,” The Kyiv Independent, February 18, 2025.

Stefan Korshak, “Ukraine Drone Production Tops 2.5 Million a Year, Aircraft Numbers on Track to Grow,” Kyiv Post, February 10, 2025.

Dmytro Basmat, “150,000 Russian soldiers killed fighting Ukraine in 2024, Syrskyi says,” The Kyiv Independent, January 20, 2025.

Yurri Clavilier and Michael Gjrstad, “Combat losses and manpower challenges underscore the importance of ‘mass’ in Ukraine” International Institute for Strategic Studies, February 10, 2025.

Ibid,.

This is absolutely the best essay I come across yet on military ground tactics in Ukraine. Maybe it’s a bit long for our attention deficit era but that doesn’t make it any less of a master class. Truly worthy of wide dissemination.

Sec. Rock, this is a masterful explication of the ground war! It is so annoying when the press conflates the loss of a few hundred meters of devastated farmland with Ukrainian “collapse”, instead of defense in depth. The Germans in the latter years of WWII were good at this too when they weren’t interfered with by higher command. Between you and “eyes only” by Wes O’Donnell, I find the best realistic analysis of the conflict.