The Triumph of the Operator

GWOT, Signalgate, and the Cult of the Operator making National Security Policy

When I first saw this post, I didn’t think much of it. Then I did a double-take when I realized it was actually JD Vance cosplaying as an operator. I’m not here to judge a guy for his hobbies or a politician for grabbing a photo op in military garb—if you’ve been around long enough, you might recall George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” moment in a flight suit or Michael Dukakis riding in a tank. But these photos reflect a deeper trend within Trump’s national security apparatus—one increasingly dominated by what some have called the “cult of the operator.” There’s a growing fixation on Special Operations Forces (SOF) and the romanticized image of the elite warrior. This mindset is significantly shaping the decision-making processes within the Trump administration’s national security team, leading to a distorted understanding of modern warfare and how best to protect American interests abroad.

The "cult of the operator" is a term used to describe the glorification and romanticization of SOF within military and political circles, particularly in the United States. It reflects an obsession with the image of the elite warrior—highly trained, rugged, and seemingly invincible—who is perceived as the ultimate solution to complex security challenges. This mindset often elevates operators to a near-mythical status, overshadowing the broader strategic, diplomatic, and conventional military considerations necessary for national security. The cult of the operator can skew decision-making by overemphasizing kinetic and direct-action solutions while downplaying the importance of intelligence, diplomacy, and long-term strategy. It has also contributed to the perception that elite military experience alone qualifies individuals for high-level national security roles, regardless of their broader policy expertise or understanding of geopolitical complexities.

But this mindset extends beyond the military sphere, influencing broader cultural narratives around masculinity and business. In popular culture and media, the elite operator archetype embodies a hyper-masculine ideal—tough, resilient, and unyielding—setting an unrealistic standard for what it means to be a "real man." This archetype promotes the idea that strength and dominance are the primary virtues of masculinity, often overlooking traits like empathy, cooperation, and vulnerability. In the business world, this mindset translates to the glorification of the "tough, no-nonsense leader" who charges ahead without hesitation, making bold and sometimes reckless decisions. Just as in national security, this fixation on the operator ethos in masculinity and business can create a distorted view of what truly makes a strong, effective leader.

There are many dimensions to this phenomenon, but one critical aspect that often goes unappreciated—and is the focus of this article—is how Trump’s national security team has become dominated by individuals with backgrounds in SOF or those who were deeply immersed in that world. For nearly the entirety of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), SOF operated under a different set of rules with minimal accountability, creating a culture where unconventional actions became the norm. This environment leads to incidents like a former Green Beret colonel turned National Security Adviser creating a group chat on a non-government approved messaging app to discuss foreign policy. Meanwhile, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) appears visibly unprepared and overwhelmed during congressional hearings, encountering accountability for her ideas for the first time.

Trump’s national security team has become a stronghold for individuals with SOF experience or those heavily influenced by the special operations mindset. Representative Mike Waltz, a former Green Beret colonel, serves as the National Security Advisor. Tulsi Gabbard, the Director of National Intelligence, brings her ties to Special Forces through the National Guard, along with her deputy, Joe Kent, a former Army Ranger and SOF veteran. Kash Patel, the Director of the FBI, previously served as the legal liaison for the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) while working at the Department of Justice. Dan Caine, currently nominated for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, served as the associate director for military affairs at the CIA—a position that closely collaborates with special forces. Even Pete Hegseth, who never served in the special forces, has become a regular presence on podcasts within the special forces industrial complex, strongly aligning himself with this ethos.1 Even Sebastian Gorka, who serves as Deputy Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Counterterrorism, has lectured special operations units on counterterrorism despite having no experience as an operator himself, yet has become a prominent advocate of this mindset.

This trend extends beyond direct advisory roles. Michael Obadal, a task force leader for Joint Special Operations Command, was nominated as the Army's No. 2 civilian official. Michael Jensen, who served with the Air Force Special Operations Command, is nominated for assistant secretary of defense for special operations and low-intensity conflict.2 Meanwhile, Hung Cao, another SOF officer, is tapped to serve as the Department of the Navy’s No. 2 civilian leader. This pervasive presence of special operations veterans and advocates within the administration reinforces the idea that elite forces are the primary solution to complex security challenges, overshadowing broader strategic and diplomatic considerations.

Given this context, it should be no surprise that the GWOT has largely continued unabated under this administration. An ISIS leader was recently killed in Iraq, airstrikes are ongoing in Yemen and Somalia, and troops remain stationed in Syria despite the official end of the decade-long civil war and the DOD drawing up plans for withdrawal. B-2 bombers were repositioned to Diego Garcia, which usually indicates they’ll be used in the Middle East. The only real difference between the Biden and Trump administrations’ policies toward the Houthis is that the Trump administration has loosened rules of engagement and expanded the target package.

It’s a curious continuity, especially given how radically different the makeup of each national security team is. Despite these differences, both administrations find themselves trapped in the same strategic dilemma, defaulting to the same flawed policies of military force. More than anything, it demonstrates that Trump’s national security team is dominated by individuals with SOF backgrounds or SOF-adjacent experience, perpetuating the continuation of the GWOT because it’s the only framework they truly understand or have experienced.

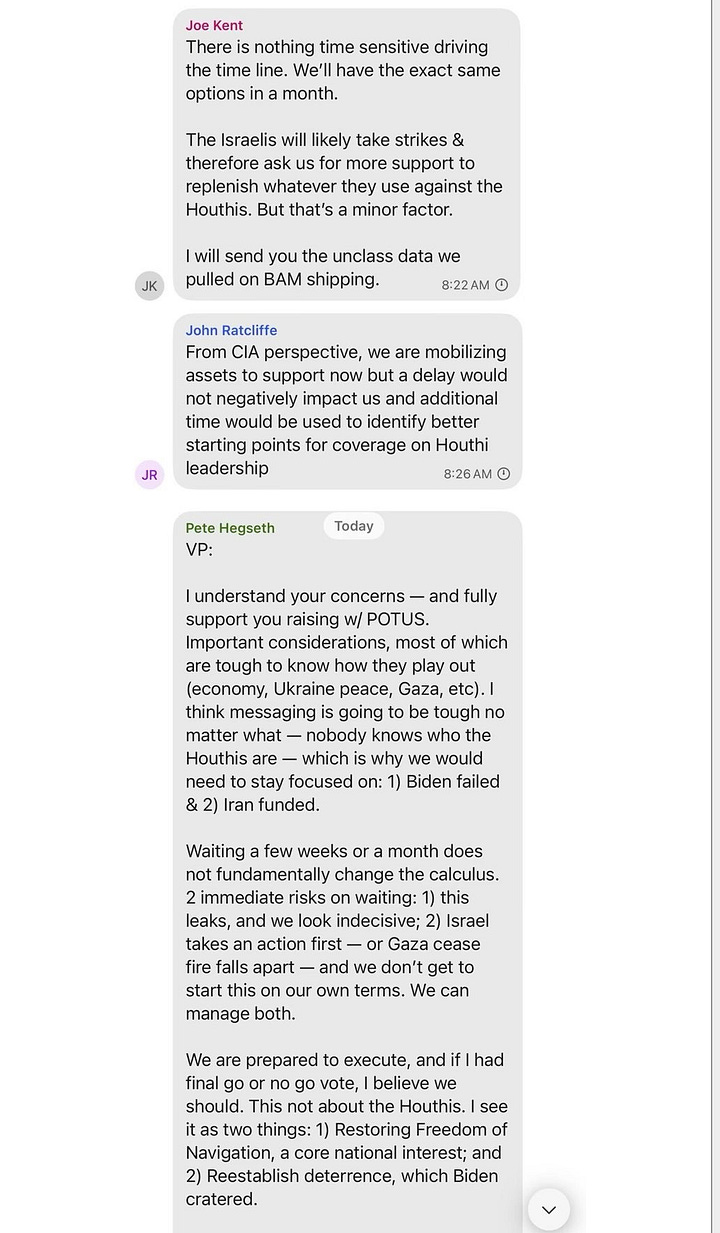

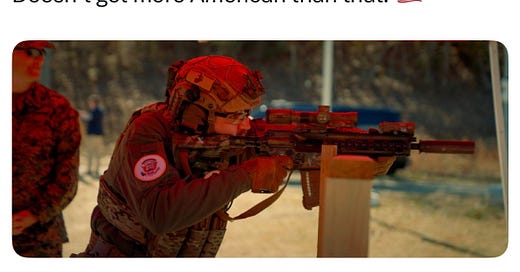

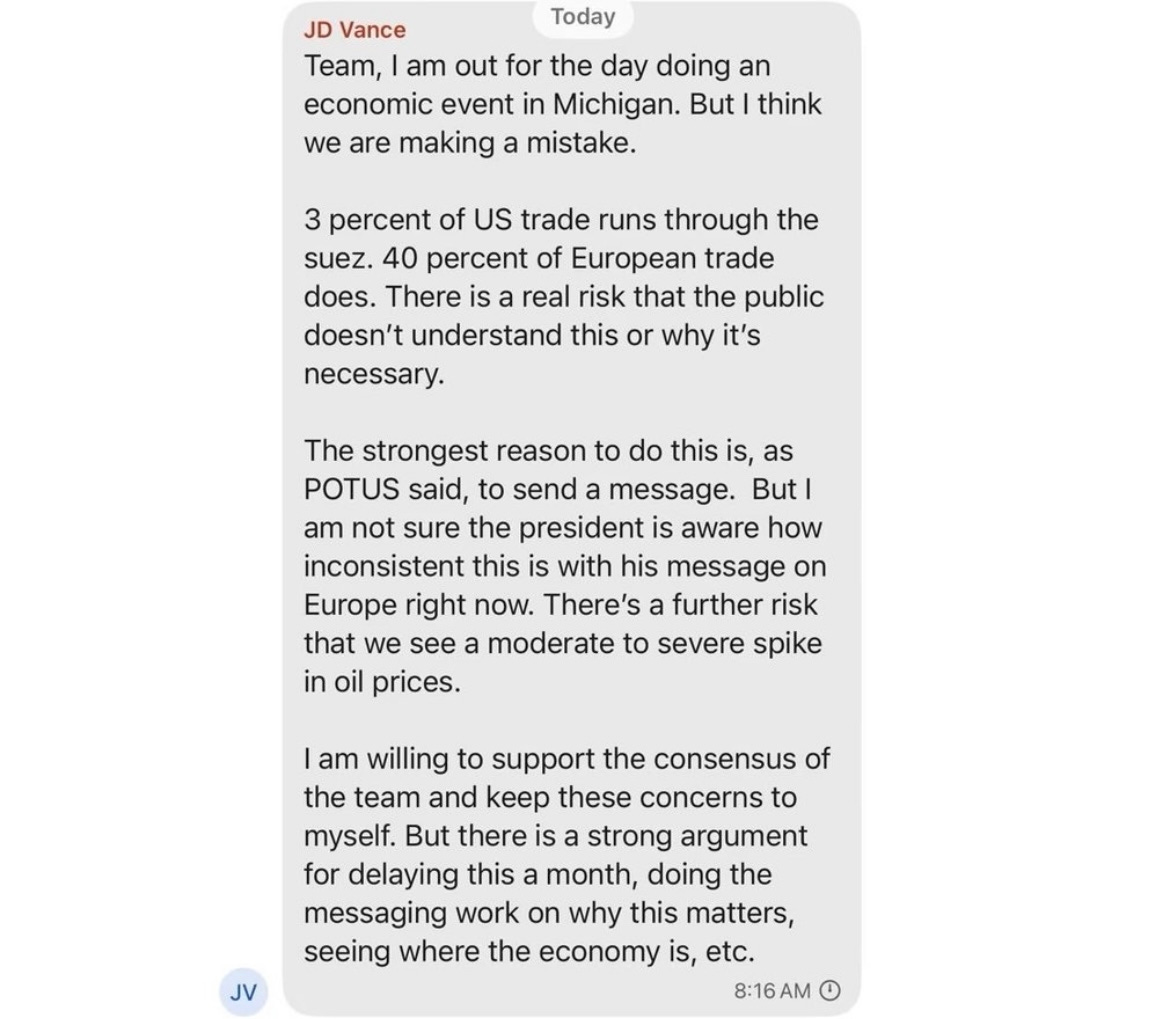

There are many dimensions to the Signal group chat leak—signalgate, groupgate, Waltzgate, whatever you prefer to call it—but it provides a rare glimpse into the administration’s national security policymaking, offering insights that usually take decades to surface through declassification. In this instance, the group chat pertains to the air campaign against the Houthis, a Yemeni Shia Muslim rebel group originating from the Zaidi sect in northern Yemen. The Houthis gained prominence during the Yemeni Civil War, capturing the capital, Sanaa, in 2014 and forcing the internationally recognized government into exile. Backed by Iran, they have been engaged in a prolonged conflict against a Saudi-led coalition, which includes the United States as a key supporter who have provided logistical support and weapons.

In response to the situation to the war in Gaza, the Houthis have intensified their actions, launching missile and drone attacks targeting Israel and international shipping routes through the Red Sea. They have declared their intent to continue these attacks until Israel ends its operations in Gaza. The United States, aiming to counter these threats and protect strategic interests such as the security of shipping lanes through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, has escalated its military campaign against the Houthis that originally started under President Biden.

Interestingly, it’s the vice-president, who has a long history of criticizing GWOT and “forever war,” is the only one that basically asks in this group chat, “What are we attempting to accomplish here?” But ironically, he endorses the most flawed part of the air campaign: sending a message. The rest of the principals are tossing around concepts and ideas, clearly trying to piece together a coherent strategy. They have a rough sense of what they think the strategic goals should look like and identify a few specific elements like oil prices, trade, sea lanes, and deterrence.

But the problem is they can’t bridge the gap between their scattered concepts and a tangible, actionable strategy (and the vice-president sees this). It’s as if they were gathering all the right ingredients without understanding the recipe. They seem to think that simply having the right components will inherently produce strategic success, but they lack the critical insight to connect those elements in a meaningful way. The result is a muddled sense of direction—an assumption that just by putting the right pieces on the board, victory will follow.

In essence, they are caught up in the allure of theoretical constructs without grounding them in practical, systematic thinking. It’s one thing to recognize the importance of sea lane control and deterrence, but without the connective tissue—without a clear rationale for how those elements interact and support broader strategic objectives—it’s all just noise. They fail to move from theory to application, from aspiration to execution. In the end, this discussion is all rendered mute by Stephen Miller, the president’s domestic policy advisor, stating the president wants the air strikes to go forward.3

What is even more ironic is that many of the same figures in this group chat are the same ones that have spent the last few years denouncing the concept of “forever war” in the Middle East and now find themselves presiding over “forever war” in the Middle East. Now in an actual position to influence and dictate policy, they essentially continue what the United States has been doing for the last 25 years. This highlights the fundamental flaw of having individuals from SOF (and what I call SOF-adjacent) dominate the national security policymaking team: the deeper issue is that under Trump, the national security and foreign policy apparatus has become disproportionately shaped by a subculture ill-equipped for the nuanced, deliberative nature of strategic policymaking. I suspect another factor is that for many of these individuals, the GWOT is all they know, and the prospect of tackling other challenges—like confronting China or bringing an end to the war in Ukraine—feels like a bridge too far or outside their lane of expertise.

Another common thread among these figures is their adherence to a flawed thesis: that America fails in war not because of strategic errors or political miscalculations but because it lacks enough elite warriors or grit to achieve victory. This mindset is rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of modern warfare, where successful military operations demand far more than just specialized combat skills and daring missions. They require robust logistical support, meticulous planning, and the seamless integration of diverse force components, including conventional ground forces, air and missile defense, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Simply put, elite warriors cannot compensate for the layered and multifaceted nature of contemporary military challenges, and the belief that they can reflects a fundamental strategic myopia.

Special forces certainly have their place and are invaluable for specific missions—sabotage, reconnaissance, targeted raids, and counterterrorism operations. These units excel when tasked with high-stakes, precise operations that demand exceptional skill and stealth. Yet, they are not, and have never been, a replacement for conventional forces in large-scale conflicts. The notion that small, agile units of highly trained warriors can single-handedly alter the course of major military engagements is both misguided and dangerously simplistic. Despite this reality, the current mindset among many in U.S. leadership continues to elevate special operations as the ultimate problem solvers, ignoring the essential components of state-on-state conflict that demand massed infantry, artillery coordination, drones, armor, and integrated air defense systems.

The cult of the operator has deeply influenced how American military power is conceptualized and employed, especially within the Trump administration, where a significant number of key advisors and officials came from the world of Special Operations Forces (SOF). For the past 20 years, SOF has operated under a unique set of rules—rules that often lacked accountability and oversight, fostering a culture of autonomy and flexibility but also one that lacked strategic depth. This mindset, cultivated during the GWOT, has become embedded in how policymakers and military leaders who now serve in the Trump administration approach conflicts. Rather than adapting to the evolving realities of 21st-century warfare, they continue to default to the same tactics that characterized the post-9/11 era.

One of the most glaring consequences of this mindset can be seen in how the United States has responded to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. In Ukraine, Russia’s once-vaunted special forces, including the Spetsnaz and other elite units, have been decimated by the grueling realities of conventional warfare. These units, initially trained for rapid, precise operations, found themselves overwhelmed by the brutality and sheer scale of sustained conventional combat. Instead of executing daring raids or precise strikes, they were forced into static defense and attrition battles, roles for which they were never intended.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian special forces, initially envisioned as conducting daring behind-enemy-lines raids and snatching high-value targets, have found themselves relegated to more mundane and labor-intensive tasks like patrolling the Dnipro River, clearing trenches, and engaging in brutal urban combat. Their skills, while invaluable in specific scenarios, have proven inadequate in the face of mass artillery barrages and mechanized assaults. The idea that tripling down on SOF capabilities will somehow resolve complex, large-scale military challenges is fundamentally flawed. Secretary Hegseth repeatedly emphasized buzzwords like “warrior ethos,” “warfighting,” and “lethality,” rather than focusing on practical and necessary questions like “how do we produce enough artillery shells?” or “how do we mobilize enough personnel to sustain a prolonged conflict?” This rhetoric is emblematic of a flawed mindset that prioritizes abstract ideals of combat over the tangible and logistical realities of modern warfare.

The emphasis on warrior culture and the glorification of combat readiness reflects an obsession with the aesthetics of war rather than the practicalities of sustaining it. While concepts like "warrior ethos" and "lethality" evoke images of gritty determination and fighting spirit, they fail to address the essential elements that make modern military operations viable: production capacity, supply chain management, recruitment, and the maintenance of a robust industrial base. War has and always demands a lot of human capital, and doubling down on a small, spartan-Esque warrior class could be fatal in a future conflict.

This mindset is not just a rhetorical flaw but a fundamental failure of strategic thinking. It represents a narrow focus on the perceived moral qualities of soldiers while neglecting the institutional and logistical foundations that support sustained military efforts. As a result, leaders like Hegseth end up promoting a culture that values symbolic strength over practical readiness, leaving the armed forces unprepared for the demands of large-scale, conventional warfare, which will almost certainly be what the next conflict involving the United States is.

The fixation on special operations emerged during the GWOT, where highly publicized raids and daring missions became the face of American military power. In the early 2000s, stories of Navy SEALs and Army Rangers taking down high-value targets captured the public imagination, fostering the myth that small, agile, and elite units could single-handedly change the tide of conflict. These narratives, fueled by both popular culture and government messaging, helped cement the operator myth as the prevailing model for military success. Popular media—from Hollywood blockbusters to best-selling memoirs—glorified the operator as the epitome of American martial prowess, reinforcing the idea that grit and skill could overcome any obstacle.

However, the reality of warfare in the 21st century has evolved far beyond the asymmetric counterterrorism operations of the Middle East. The United States now faces potential conflicts with near-peer adversaries like Russia and China—adversaries that deploy conventional military forces on a massive scale. These adversaries employ combined arms tactics, cyber operations, advanced missile systems, and comprehensive logistics networks to maintain a sustained military presence and firepower. Special forces, while still crucial for specialized missions, will not be decisive in battles that involve thousands of armored vehicles, intricate artillery coordination, drone swarms, and sustained air superiority efforts. The tactical brilliance of small units cannot replace the operational and strategic necessities of large-scale conflict and relying on them as a primary solution is a recipe for strategic failure.

What makes the current obsession with special operations even more concerning is that it overlooks the lessons learned from past conflicts where reliance on elite units led to tactical success but strategic failure. In Vietnam, the U.S. deployed special operations to disrupt Viet Cong logistics and leadership, but these successes did not translate into strategic victory because the broader political and social dynamics were neglected. Similarly, in Afghanistan and Iraq, daring raids and targeted strikes took out countless high-value targets, but they failed to stabilize the countries or build sustainable governance structures. Despite these lessons, the cult of the operator continues to dominate strategic thinking within segments of the U.S. defense establishment.

They have become so entrenched in the operator mindset that they fail to see how its overemphasis contributes to a cycle of continuous conflict without clear resolution. The cult of the operator not only distorts strategic planning but also ensures that the United States remains mired in conflicts it cannot decisively win. It perpetuates the illusion that tactical brilliance alone can secure victory, while neglecting the broader and more complex realities of modern warfare. To break this cycle, it is essential to move beyond the mythology of the operator and recognize the importance of a more comprehensive, multi-dimensional approach to military strategy and national security.

In the end, the cult of the operator represents a fundamental misunderstanding of modern military strategy and national security policy. It elevates a narrow and romanticized vision of elite warriors as the ultimate problem solvers while neglecting the broader and more complex elements essential for strategic success. This mindset has not only shaped Trump's national security apparatus but has also permeated American military culture, fostering a cycle of endless conflict where tactical brilliance is mistaken for strategic wisdom. As the United States faces new and evolving global challenges, clinging to outdated paradigms rooted in special operations dogma will only deepen strategic failures and prolong unnecessary conflicts. To move beyond this flawed legacy, it is crucial to foster a more balanced approach to national security—one that values diplomacy, comprehensive planning, and the integration of diverse military capabilities, rather than relying solely on the myth of the elite operator.

In fairness, his nomination isn’t necessarily out of the ordinary.

This raises a whole set of different questions, but that is for someone else to dissect.

I tend to think you have identified a sub-set of the SOF community and a mentality present within that. But, that is not reflective of the body of SOF.

“The United States now faces potential conflicts with near-peer adversaries like Russia and China—adversaries that deploy conventional military forces on a massive scale. These adversaries employ combined arms tactics, cyber operations, advanced missile systems, and comprehensive logistics networks to maintain a sustained military presence and firepower. Special forces, while still crucial for specialized missions, will not be decisive in battles that involve thousands of armored vehicles, intricate artillery coordination, drone swarms, and sustained air superiority efforts.”

As a biased former SOF guy, this premise posits we are going to be in direct combat with one or two nuclear armed adversaries. That might occur. But, it is equally likely that the conflict will play out along the seam states, much like Cold War 1.0. That is the Green Berets’ foundational mission. I like the “Quiet Professional” mantra more than not, but that is also why the louder one are dominating parts of the conversations.

You are not wrong that GWOT caused a weird change in SOF. It became more present in society in a way that is not always positive. It is also true that to a hammer everything looks like a nail. But, there are plenty of people in SOF that saw what happens when we overreach and try to be all things to all men and resist that fully.

This fixation does nothing to address what I have seen firsthand decades as the major flaw in US strategic planning - the repeated failure of the leaders of the Armed Forces to explain to the suits that military force cannot give them the desired outcome, at least not military force alone.