The "Thucydides Trap" Trap

U.S.-China Relations and the Misuse of History

In the world of international relations, few concepts have captured as much attention—and sparked as much debate—as the “Thucydides Trap.” Brought to prominence by Harvard political scientist Graham Allison, the term suggests that conflict is almost inevitable when a rising power threatens to displace an established one, a dynamic often invoked to frame the strategic rivalry between the United States and China. Lauded as a National Bestseller and praised by figures like Henry Kissinger and Joe Biden, Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? has become a staple of policy discussions and academic syllabi. Yet beneath the widespread acclaim lies a deeply flawed analysis, one that risks oversimplifying history and perpetuating a fatalistic narrative that could shape policy in dangerous ways. Far from an inescapable destiny, the lessons of history and the nuances of modern geopolitics suggest that the so-called “trap” may be more myth than inevitability.

The term “Thucydides Trap” is derived from a passage in the ancient Greek historian Thucydides' work History of the Peloponnesian War, where he explained the causes of the conflict between Athens (the rising power) and Sparta (the ruling power) in the 4th century BC. Thucydides famously wrote

It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.

Allison defines the “Thucydides Trap” as “the severe structural stress caused when a rising power threatens to upend a ruling one.”1 More articles by Allison using this term previously appeared in Foreign Policy and The Atlantic. The book, published in 2017, was a huge hit, being named a notable book of the year by the New York Times and Financial Times while also receiving widespread bipartisan acclaim from current and past policymakers. Historian Niall Ferguson described it as a “must-read in Washington and Beijing.”2 Senator Sam Nunn wrote, “If any book can stop a World War, it is this one.”3 A brief search on Google Scholar reveals the term “Thucydides Trap” has been cited or used nearly 19,000 times. In 2015, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull even publicly urged President Xi and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to avoid “falling into the Thucydides Trap.”4 One analyst observed that the term had become the “new cachet as a sage of U.S.-China relations.”5 The term has become so prominent that it is almost guaranteed to appear in any introductory international politics course when discussing U.S.-China relations.

Allison wrote in his essay “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” in The Atlantic published in 2015, “On the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment” forewarning, “judging by the historical record, war is more likely than not.”6 A straightforward analysis of the 16 cases in the book and previous essays might indicate that, based on historical precedent, there is approximately a 75 percent likelihood of the United States and China engaging in war within the next several decades. Adding the additional cases from the Thucydides Trap Website would still leave a 66 percent chance, more likely than not, that two nuclear-armed superpowers will go to war with one another, a horrifying and unprecedented proposition.7

With such alarm, it's no surprise that the concept gained such widespread attention. The term is simple to understand and in under 300 pages, Allison delivers a sweeping historical narrative, drawing striking parallels between events from ancient Greece to the present day.8 International Relations as a field often struggles to break through in the public discourse, but Destined for War broke through, making a broad impact on academic and popular discourse.

The allure of the “Thucydides Trap” lies in its simplicity, which is also its most significant flaw. The historical framework oversimplifies complex dynamics, as the dataset of 16 cases involving rising powers challenging established ones implies that correlation equals causation, despite the vastly different contextual factors that led to each conflict. This doesn’t mean there are historical parallels or lessons to be learned in the context of U.S.-China relations, but the deterministic framing of a “trap” implies that war is inevitable, disregarding the capacity of states to make strategic choices to manage conflict, avoid conflict and even turn rising powers into allies. As one critic observed, “Allison’s Thucydides Trap, keyed directly to a single line in isolation, is thus at best the first step on a considerably longer path.”9

The very first example he uses in the book (but isn’t included in the popular chart) is the peaceful power transition between Spain and Portugal in the late 15th century, which is attributed to economic and military strain.10 The peaceful power transition between the U.S. and Great Britain in the late 19th century also challenges the narrative of inevitability.11 More examples that aren’t included are relations between Prussia (the rising power) and Great Britain (the ruling power) after the Seven Years War (1756–1763), which were fraught to the point that they might go to war with one another, but the two countries later formed the foundation for the coalition that would battle against Napoleon in the early 19th century.12

By prioritizing dramatic historical parallels over a more comprehensive analysis, Allison risks perpetuating a fatalistic narrative about U.S.-China relations that could become a self-fulfilling prophecy if adopted by policymakers without critical reflection. It’s not a coincidence that the rise of a “bipartisan consensus” toward a more aggressive foreign policy towards China has coincided with the increasing use of the term.13 The extensive press coverage and glowing reviews demonstrate that many U.S. policymakers have taken Allison's concept to heart, with Allison himself briefing National Security Council staffers at the Trump White House on the Thucydides Trap in April 2017.14 The idea of a “trap” particularly appeals to policymakers who want a more hawkish approach to China because it bypasses the question of whether the United States should view China as a rival, instead presuming that history has already determined it to be so—or that it inevitably will be.15 This deterministic framing oversimplifies a complex relationship and risks locking policymakers into a confrontational mindset, regardless of the strategic choices available to manage or even avoid conflict. Although Allison lays this groundwork precisely so he can propose alternatives to prevent war, his repeated assertions that history dictates its inevitability ultimately narrow the focus to a single, predetermined path.16

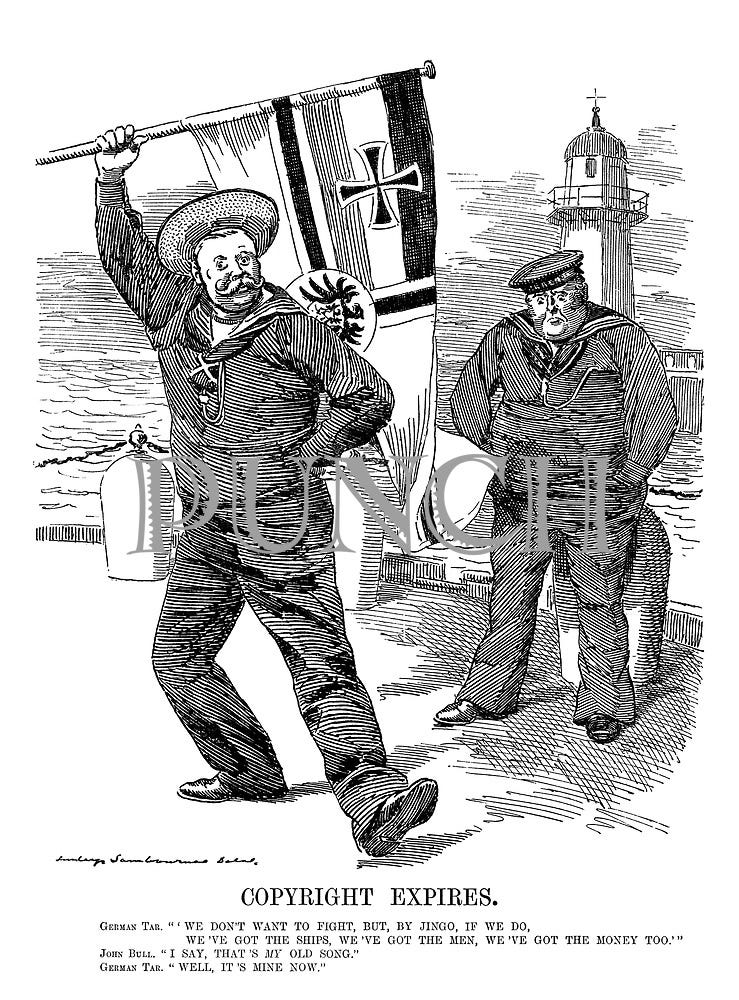

Allison dedicates an entire chapter to examining the German-British rivalry of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.17 At first glance, the parallels are striking: much like China today, historically a land power, undertaking an ambitious naval buildup to challenge the United States, the dominant maritime power of the last seven decades just as Germany did against Britain. Similarly, as Belgium played a pivotal role in triggering conflict between Germany and Britain, Taiwan might be a comparable flashpoint in contemporary geopolitics.

Digging below the surface, though, significant discrepancies show up. By 1914, Germany had already outpaced Great Britain in nearly every measurable metric of economic and military power. As the Historian and Yale Professor Paul Kennedy summarizes,

Germans enjoyed far higher levels of education, social provision, and per capita income than Russians, the nation was strong both in the quantity and the quality of its population; in effect, it could sustain a very large regular army, and summon millions of reserves to the colors, with less strain than virtually every other combatant. Furthermore, although its military expenditures were enormous by 1914, they consumed less of the national income than those of any other state except Britain and the U.S., that is to say, the enormous growth of the German economy was allowing it to bear the burden of armaments without undue discomfort. If, by the eve of war, its total energy production and its share of world trade had not yet overtaken Britain's, it was already ahead on most other measurements of national economic power. Its percentage of world manufacturing production was bigger, as was its total industrial potential. Its steel production was more than the British, French, and Russian output combined! Its lead in newer industries-chemicals and dyestuffs, electricals, machine tools, optics-was even more marked. Behind this lay a broad-based infrastructure of good internal communications, a powerful and rich banking system, large numbers of engineers, technicians, and craftsmen, and impressive educational institutions.18

In many ways, Germany was already the “ruling” power and didn’t even have to fight a war, but it speaks to broader issue with Allison’s methodology. The definitions of a “ruling” and “rising” powers are vague and open to interpretation, allowing him to include cases that support his argument selectively. There are no concrete metrics for measuring military or economic power to definitively classify a nation as a “ruling” or “rising” power. Instead, these labels entirely depend on the context of a chosen rivalry, whether geographically, economically, or militarily.

Allison even mentions briefly that Germany was a “ruling” power on the European Continent stating that Russia as a “rising” power. However, he doesn’t call the German-Russia relationship a trap but simply a “Thucydian dynamic.”19 In fact, the “Thucydides Trap” might be more applicable to Germany and Russia, as Russia was undeniably a rising power. As Paul Kennedy wrote,

The vast growth in its population impressed all those who immediately translated that element into real military strength. Its army of over 1,300,000 in 1914 was far larger than any other, and backed by about 5,000,000 reserves-figures which made the younger Moltke sweat and French revanchists crease with pleasure. Russia's military expenditures, too, were extremely high and, with the "extraordinary" capital grants on top of the fast-rising "normal" expenditures, may well have exceeded even Germany's total. Railway construction was proceeding at enormous speed- threatening within another few years to undermine the calculations upon which the Schlieffen Plan was based-and money was also being poured into a new Russian fleet. It is, moreover, worth noting that it was not merely the German and Austro-Hungarian General Staffs, looking to their eastern frontiers, which feared the Russian military colossus; there were also certain Britons apprehensive about the impact of Czarist power in Asia.20

Kennedy would fittingly call Russia of the early 20th century, “the coming power” but Allison's omission of a deeper analysis of the Germany-Russia relationship in the context of the “Thucydides Trap” raises questions about the framework's consistency.21 If Germany was the “ruling” power on the continent and Russia the “rising” power, the dynamics, backed up by measurable data, align more closely with Thucydides’ original premise than Allison acknowledges. Russia's rapid population growth, burgeoning military capacity, and accelerated infrastructure development, as Kennedy describes, created a tangible sense of threat for Germany, just as Athens’ rise alarmed Sparta. There were also territorial disputes over Poland and a historic rivalry dating back centuries. They also had the benefit of geography being right next to each other whereas Britian and Germany would have trouble getting at one another because of the North Sea.

It should be noted that in the case files, Allison states that Russia and France “supported” Britain against Germany but that is not well defined either.22 Including an individual case between Germany and Russia would complicate Allison’s thesis, as it would suggest that rising and ruling powers can exist concurrently within multiple overlapping spheres of influence. It also undermines the simplicity of his dataset by demonstrating that not all “traps” involve a singular rising and ruling power on a global scale. Instead, this scenario reveals a more nuanced interplay of regional and global factors, where alliances, geography, and economic interdependence profoundly influence outcomes. Ignoring such complexity weakens the analytical rigor of the “Thucydides Trap” and exposes its limitations in accounting for multidimensional power dynamics.

The only significant advantage Great Britain held was its naval superiority. Allison devotes several pages to analyzing the naval arms race between the two nations, seemingly charting a path toward conflict.23 However, he notes that the arms race did not directly cause the war but merely “laid the foundations for it.”24 This implies that the British-German rivalry was more complex than a straightforward clash between a rising power and a ruling power. In reality, the British-German rivalry was often evolving shaped by a web of alliances, economic interdependence, and broader continental dynamics.

Allison also overlooks the critical detail that, in the years leading up to the war, political leaders in Germany and Great Britain were actively pursuing a détente to foster more stable relations and leadership between the two powers.25 Neville Chamberlin, the future prime minister, told a German embassy official in 1903 that Germany should become a member of the Triple Alliance (what would later be the Allies in World War I).26 Kaiser Wilhelm II told his grandmother, Queen Victoria, just before her death, “We ought to form an Anglo-German alliance; you keep to the seas, while we would be responsible for the land; with such an alliance, not a mouse could stir in Europe without our permission.”27 Bethmann Hollweg, the German Chancellor from 1909-1917, made a cooling of relations with Britain the centerpiece of his foreign policy agenda.28 British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey is reported to have said, “So long as Bethmann Hollweg is Chancellor, we will cooperate with Germany for the peace of Europe.”29 The historian Margaret MacMillan wrote, “If Germany and Britain had formed an alliance, it would be easy to find explanations for that.”30 None of this suggests that Germany and Britain were locked into a fait accompli to go to war with one another; instead, it was a consequence of the volatile international system of the time, primed like a powder keg that drove Europe into war.

The British-German case, considered one of the strongest examples (as evidenced by its dedicated chapter), is deeply flawed, reducing a nuanced historical relationship into a simplistic binary dynamic and thereby diminishing the Thucydides Trap's relevance as a framework for analyzing what was a complex and oftentimes contradictory rivalry. Before World War I, Britain and Germany found ways to compromise and reconcile their interests. They avoided war over issues such as colonial territories overseas and the Baghdad-Berlin railway, and they even collaborated to reduce tensions during the Balkans crisis.31

We should remember it was the assassination of an Austrian Archduke that kicked off World War I, not something that Germany or Britain deliberately did. As Kennedy astutely observed, “The First World War offers so much data that conclusions can be drawn from it to suit any a priori hypothesis which contemporary strategists and politicians wish to advance.”32 In other words, the causes and course of World War I was complicated and to reduce the German-British rivalry to a 14-year naval race is a gross oversimplification of history. It ultimately weakens the Thucydides Trap’s applicability, as it fails to account for the broader complexities of international relations and the potential for peaceful resolution even in the most competitive and tense rivalries.

The Thucydides Trap can be interpreted in several ways regarding U.S.-China relations. Allison's first and more ambitious version suggests that the two countries could go to war solely due to shifts in their relative economic power.33 The second, more cautious interpretation posits that war may arise from the interplay of perceived national interests and changes in objective power dynamics.34 The third imagines that China would be in America’s shoes, deciding to enforce its own “Monroe Doctrine” in East Asia, therefore setting up an inevitable collision course with the United States.35 However, one cannot reasonably conclude that states are “destined for war” based solely on power shifts (which aren’t defined) within a dataset that solely selects for rivalries—a reality shaped by a state’s intentions and actions. This doesn’t mean that a historical analysis of great power rivalries might offer lessons, but Allison’s method is problematic, and its widespread acclaim means policymakers are drawing the wrong lessons from history because if there is a more likely chance than not that the United States and China will go to war with another in the coming years, as history suggests, then there is little point to exploring alternative strategies or approaches.

The trap also assumes that a rising power will continue its ascent indefinitely. This is important because Allison cites fear—when the rising power “surpasses” the ruling power as one of the key factors contributing to “inevitable” war.36 When the book was published in 2017, it did seem likely that China was about to pass the United States in terms of GDP, a key metric of state power for certain scholars. However, events have taken a turn. China faces significant structural challenges, including an impending demographic crisis, economic stagnation after Covid-19, and a military frequently disrupted by anti-corruption purges. These issues hardly suggest an unstoppable force poised to dominate East Asia. Similarly, the United States grapples with significant challenges, such as domestic political instability, wealth inequality, and a military burdened by extensive global commitments. In truth, either nation might refrain from going to war simply because neither is in a position to do so effectively. The Portugal-Spain case in the late 15th century, where the two countries did not go to war because of economic and military strain, might be most applicable. Spain had spent centuries battling the Moors (Spanish Muslims) in the “Reconquista” and was militarily exhausted. Portugals adventures in the New World had brought tremendous riches but also strained its economy. This historical parallel underscores that war is not an inevitable outcome of great power competition; instead, the constraints of internal challenges and strategic exhaustion can often serve as powerful deterrents.

It is also no coincidence that all of the case studies he cites involving nuclear-armed superpowers after World War II avoid culminating in war.37 Modern international relations are shaped by unique dynamics, including nuclear deterrence and globalization, which were absent throughout history, making direct comparisons problematic. The interconnectedness of global economies and the catastrophic risks of nuclear conflict act as powerful incentives for restraint, fundamentally altering the calculus of state behavior. To claim that war between the United States and China is almost inevitable based on conflicts like those between the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries over territory in Southwestern Europe and the Mediterranean or the Dutch and England in the late 17th century over trade rights is a profoundly flawed and ahistorical comparison. In the modern era, historical patterns of great power rivalry hold limited predictive value.

The “Thucydides Trap” thrives on its simplicity, but its deterministic framing is leading policymakers astray by reducing complex relationships to historical inevitabilities. Instead of treating history as a prophecy, we should use it as a guide—one that underscores the importance of diplomacy, strategic foresight, and adaptability. The U.S.-China rivalry is not preordained to end in conflict, and embracing this nuanced understanding is the first step toward ensuring it doesn’t. History offers valuable lessons, but it should inform strategy, not dictate it.

References

Allison, Graham. 2017. Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Allison, Graham, September 24, 2015, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/united-states-china-war-thucydides-trap/406756/

Kennedy, Paul M. 1984. "The First World War and the International Power System." International Security 9, (1) 7-40.

Lynn-Jones, Sean M. 1986. "Détente and Deterrence: Anglo-German Relations, 1911-1914." International Security 11, no. 2 121–50.

MacMillan, Margaret. 2014. The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. New York: Random House.

Misenheimer, Alan Greeley. 2019. Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War. NWC Case Study, Washington: National Defense University.

“Thucydides's Trap” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. https://www.belfercenter.org/programs/thucydidess-trap

Graham Allison, Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 29.

Ibid., iii.

Ibid., vi.

Quoted by Alan Greeley Misenheimer, Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War (Washington: National Defense University, 2019), 8.

Misenheiemer, 1.

“Thucydides's Trap Case File” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, accessed December 31, 2024

Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” The Atlantic, September 24, 2015.

Misenheimer details what Thucydides actually said about the origins of the Peloponnesian War, 10-17.

Misenheimer, 12.

Allison, 246-247.

Allison devotes only two pages to this case study, 271-273. For more details on this power transition, see Kori Schake, Safe Passage: The Transition from British to American Hegemony (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2017).

For details on this rift and later reconciliation, see Rose, J. Holland. “Frederick the Great and England, 1756-1763.” The English Historical Review 29, no. 113 (1914): 79–93 and Jeremy Black, “Essay and Reflection: On the ‘Old System’ and the ‘Diplomatic Revolution’ of the Eighteenth Century.” The International History Review 12, no. 2 (1990): 301–23.

See for example, press release from The House Select Commitee on the CCP from December 23, 2023. “A strong, bipartisan consensus in Washington has emerged to end the Chinese Communist Party's use of economic coercion to undermine America's national security and our values.” https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/media/press-releases/select-committee-adopts-proposal-reset-economic-relationship-peoples-republic#:~:text=A%20strong%2C%20bipartisan%20consensus%20in,national%20security%20and%20our%20values.

Allison was also giving briefings to members of Biden’s NSC. David Ignatius, “The strategist in the hurricane,” The Washington Post, December 31, 2024.

Interestingly, Allison advocates for a more restrained U.S. approach toward China.

Allison, 187-230.

Allison, 55-80.

Paul M. Kennedy, "The First World War and the International Power System" International Security 9, (1) (1984): 18.

Allison, 81-82.

Kennedy, 16, 17.

Kennedy, 17.

In the chapter on the British-German rivalry, Allision makes little mention of the role France and Russia play.

Allison, 68-83.

Allison, 80.

See Sean M. Lynn-Jones, “Détente and Deterrence: Anglo-German Relations, 1911-1914.” International Security 11, no. 2 (1986): 121–50.

Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (New York: Random House, 2014), 49.

Quoted by MacMillan, 63.

Lynn-Jones, 127.

Quoted from Lynn-Jones, 126.

MacMillan, 63.

Lynn-Jones, 129-132.

Kennedy, 37.

Allison, 6-12, 19-24.

Allison, 154-184.

Allison, 89, 106.

Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”

The “Potential Additional Cases” on the Thucydides' Trap website include Iran and Iraq as a case where a rising power went to war with a ruling power but neither country had nuclear weapons.

Excellent takedown! Almost exactly what I've wanted to write myself for years!

Alison is another Ivy League fad artist writing to satisfy the ego of a certain class of American. It's utter pseudoscience. That anyone dares to call what he put together "data" is a big part of why so many academic fields are trash.

He is simply constructing the world he wants to imagine exists, selling membership tickets to the western secular church. Thinkers like him are why, if there is a war, China is going to eat us alive. They've got their issues, but they respect hard science. Our leaders are happy to lose so long as they maintain a captive audience sitting in the pews.

Problem 1: What is a "Great Power" anyway? Who decides?

Problem 2: What constitutes war? How much violence across what span of time? This isn't an arbitrary concern - World War Two has a different start date depending on who you ask.

Problem 3: oh ffs, there's no point in listing them all out. The fact that nonsense like Alison's work gets talked about as if it isn't just a scholars egoist fantasy is why I never pursued a doctorate in IR. Any serious Geographer can take him apart in minutes.

Anyway, there's my rant in response to a well-written piece. Death to the Thucydides Trap. If it's named after something from ancient Greece, it's probably a scam.

It also misunderstands Thucydides: https://scholars-stage.org/everybody-wants-a-thucydides-trap/