The Blue Sky and Canned Sun

The Atom Bomb and Taiwanese Sovereignty in the Age of American Retreat

(Note: this is a guest article by “George”)

The question of nuclear proliferation in East Asia has been on every tongue for the last several years. Japan and South Korea have been the obvious favorites but recent events reinvigorate the question of Taiwanese nuclear acquisition. I have been writing this piece for a few weeks now, prompted by the obvious questions of American assurance to allies in a presidency with such unreliable instincts. Then White House intrigue reporting dropped a bombshell in the natsec community’s lap. Rumors swirled of some kind of internal push for a deal with Beijing on Taiwan. The level of support for, and origin & nature of, this deal were unclear. Some called it the “Taiwan for Tiktok” deal. A day later the White House issued a formal statement following Trump’s meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru which calmed the mood somewhat. Notably, it clarifies that we “oppose any attempts to unilaterally change the status quo [across the Taiwan Strait] by force or coercion.” But the ratchet of nuclear anxiety is one-way.

A number of observers, this author included, have been quietly worried about this possibility for years. The American hemispheric obsessions of the “National Conservative” wing of the party, the increasingly anti-trade bent of the party and the general distaste in the new GOP for any international commitment or expense of blood and treasure on behalf of another have borne new fears of abandonment and self-sufficiency among allies. East Asian allies have particular cause for fear. Security architectures in the Western Pacific are fragile compared to those in Europe; ASEAN relations with the People’s Republic of China are ambivalent, and while security ties between Japan and South Korea have tightened in recent years the relationship is still complex.

When it comes to the defense of Taiwanese sovereignty, Japan has been fairly vocal about support, although concrete aspects are a mixed bag. South Korean involvement is complicated by the nuclear sword of Juche Damocles hanging over their head. (I note here now, before the pitchforks come out, that I am writing this article from my narrow position as a nuclear matters expert and not a dedicated Taiwan watcher, nor an expert on South Korea or Japan. I lean on a few others for deep knowledge on these topics, several of whom are active on Twitter & bluesky - @strategictrends on Twitter, @thrustwr.bsky.social and @chen-yenhan.bsky.social first among them.) In any event, while the militaries of South Korea and Japan are no slouches, it is unlikely that they alone could conventionally defeat a PLA gamble for Taiwan; nor can the ROCA itself hold out indefinitely although it could delay and bloody the PLA. The PLA of 2025 is a large, modernized, and competent force. Whenever we see such an asymmetry of military power wedded to such existential stakes, we should expect to see nuclear temptations. Taiwan, as a matter of fact, has already entertained such temptations more than once, pulling back each time for various reasons. Will the late 2020s be different?

Weapons on Demand

I am assuming that you, dear reader, need no introduction to nuclear weapons or why countries want ‘em.1 For small countries threatened by territorially revisionist, conventionally and economically superior great powers - and when the goals of those great powers are so totalizing and so catastrophic for the victim - the rationale for nuclear weapons is especially clear. The cost to Taiwan and especially Taiwanese political and military elites of being conquered by the PRC is total. The cost of pursuing nuclear weapons may be severe, and the risks of sparking a PRC war of preemption may be high. But when presented with the apparent choice of certain doom, or near-certain doom, the crude game-theoretic correct choice is near-certain doom. Unfortunately, as we will see, the real world does not always comport with simple theory. There are compelling reasons why Taiwan might continue to refrain from nuclearization even under US abandonment, and there are compelling reasons to think Taiwan could not nuclearize in a viable timeframe no matter what. We will address the possibility and then the wisdom.

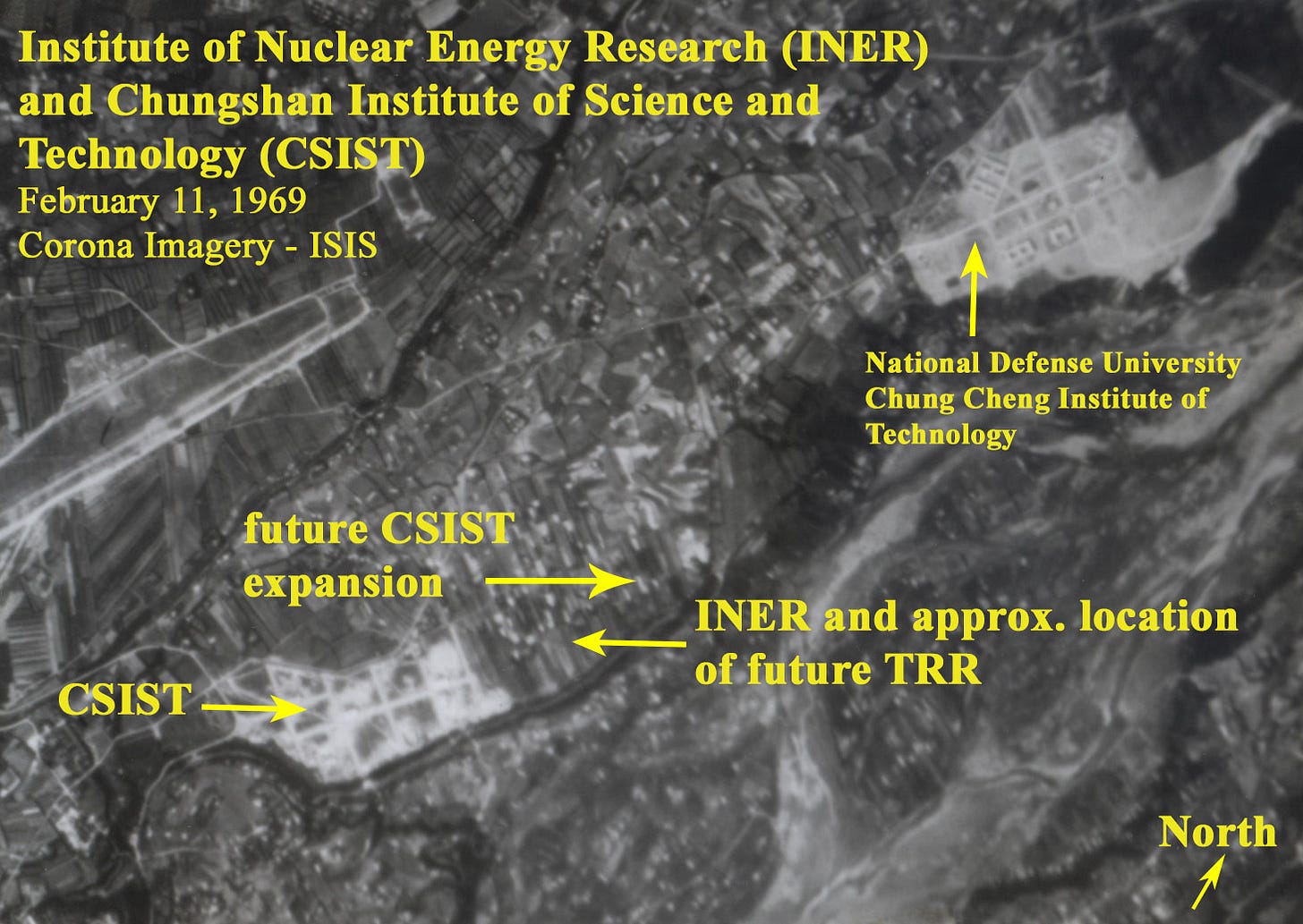

Taiwanese political leadership first explored nuclear arms in the 1950s, probably after the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis.2 The PRC’s 1964 Lop Nur atomic bomb test accelerated the work. In 1967 the Chungshan Institute of Science and Technology allocated $140 million for the acquisition of three key nuclear weapon technologies: a reactor capable of producing weapons-grade plutonium, a plant for chemically separating the plutonium from the rest of the irradiated fuel, and ballistic missiles. A heavy-water moderated Canadian NRX-type research reactor was purchased under these auspices; it was installed at the Institute for Nuclear Energy Research in Taoyuan City as the Taiwan Research Reactor.3 Chiang Kai-Shek may or may not have personally supported the program – even intimately familiar sources disagree on this – but we do know that it competed with the civilian nuclear power program for resources and political support. Scientists and military leaders never seem to have agreed on the wisdom or viability of seriously pursuing nuclear weapons in this period. More than once, dissenters covertly warned the United States about proliferation risks, such as the construction of a “hot lab” for plutonium separation work.

Throughout the early 1970s, the CIA and State Department could not themselves make up their mind on whether Taiwan could or would pursue nuclear weapons, but in 1974, US diplomats did formally demand a halt to any Taiwanese weapons development. By 1976, Taiwan was formally committed to neither developing nuclear weapons nor pursuing spent-fuel processing capabilities able to produce weapons-grade plutonium from reactor wastes. Chiang Kai-Shek’s death and succession by Chiang Ching-Kuo in 1975, and the subsequent democratization process, seem to have further stalled any weapons work. Rumors cropped up again in the late 1980s; a colonel involved in a putative program defected in 1988 and later that year the Reagan administration allegedly pressured Taiwan to halt even tangentially weapons-relevant research. TRR shut down and by 1991 almost all of Taiwan’s spent nuclear fuel had been dispositioned at the Savannah River Site in the United States.

Since the Cold War Taiwan has only further reduced the size of her nuclear industry. The only active reactor left on the island is a tiny TRIGA-type reactor for making medical isotopes and conducting basic research. The proliferation risks from this reactor type are considered to be essentially zero. Thus we are forced to conclude, based on the available open-source literature, that Taiwan’s material ability to conduct a crash bomb program is likely limited. In 1974 a now-declassified CIA assessment estimated that Taiwan was about five years from being able to fabricate a device. One could make assumptions about how much technological progress they may have made in design maturity in the 80s, but any timeline gains on that end may well be erased by their present lack of material. Any pathway involving surreptitious enrichment activities, diversion of special nuclear material or un-safeguarded precursor material, or some sort of exotic or innovative weapon design meant to evade international safeguards must remain in the realm of speculation. Hardly a basis for sober discussion. Take it to Fort Belvoir or the CIA if you must. With our rough assumption in hand that Taiwan is years, not months, from a bomb, where does this leave them strategically?

Running the Gauntlet

At first glance Taiwan does still seem to fit our expectations for nuclear proliferation. In fact, they are literally a textbook case of what Vipin Narang identified several years ago as a “hiding” strategy.4

Although Narang only covered Taiwan’s earlier efforts, these criteria all seem to still apply. The domestic consensus is the only question mark.5 If the United States withdraws the expectation of protection, or even if we signal that we are likely to accommodate the PRC to avoid war (such a signal might include the abandonment of Ukraine and the accommodation of Russian preferences in negotiations…) the “major power immunity” criterion only becomes more evident.6 In my estimation, the most dangerous link in this decision chain is Taiwan’s vulnerability to military prevention.

Many proliferation scholars (hi @nickkodama.bsky.social) argue that there is a paradox in proliferation: security environments that would seem to most clearly motivate the acquisition of nuclear weapons also tend to make the real-world, time-consuming and difficult to hide the process of acquiring nuclear weapons unacceptably dangerous. This is an argument I have had many times with Ukraine proliferation hawks in various settings, and I believe it applies even more clearly to Taiwan. The PLA’s space- and air-based technical surveillance, HUMINT penetration of Taiwan, and ability to conduct precision air and missile strikes against Taiwanese nuclear infrastructure are generally considered to be greater than Russia’s respective capabilities of such against Ukraine.7 A counterproliferation campaign using clandestine, international political, or kinetic means, or possibly an outright war of preemption, would be strategically sensible and likely within the PLA’s capabilities before Taiwan could sprint to a bomb.

There is a counterargument that Taiwan could hedge her bets and slowly creep up to some breakout capability while the extended deterrence umbrella is still open. Given that Taiwan got rapped on the knuckles for this exact behavior twice before, one wonders if their modern leaders believe the third time is a charm. At a more theoretical level, if the extended deterrent umbrella is reliable enough that you’d expect it not to snap shut as soon as you started chasing a bomb, it’s probably reliable enough that you’d prefer to keep relying on it. Beneficiaries may pursue varying degrees of nuclear latency, but empirically, it seems that fast moves and sudden deviations from the trend get noticed. Japan and South Korea could threaten Obama with future nuclearization when we talked in the abstract about closing the umbrella, but if either of them were starting from near zero while under acute military threat, and we had already closed the umbrella, the proposition seems more hollow. This is, again, the position Taiwan may well be in soon.

Assuming Taiwan is notionally able to sneak a fully fledged weapon program into existence, we have to ask ourselves what a suitable deterrent even looks like.8 There are four major schools of thought on what “enough” nuclear deterrence looks like.9 These schools are theoretically agnostic as to which state is deterring whom, although in reality, the nature of the dyad actually matters a lot. The lowest threshold is the “existential deterrent” camp. This camp holds that you really just need a bomb, and maybe not even a more advanced delivery mechanism than a ship pulled into port or a van slipping past border guards. The thinking is that, since the cost of even a single small nuclear device going off in a major city is catastrophic, states will not go to war even in the face of an uncertain risk. This argument has some explanatory power for why Israel has not tried to wipe the Ayatollah off the map, or for why the US has never made good on that infamous promise to “rain fire and fury” on Pyongyang. The flip side is that, if you look at American and Israeli defensive capabilities relative to North Korea’s arsenal or Iran’s breakout capability…you are forced to conclude that if pressed, the US/Israel could feel pretty confident in their respective defensive systems riding out the limited attack with a solely monetary cost rather than the incineration of Austin, Texas. The PLA maintains large and technically sophisticated air and missile defenses and might well feel that the conquest or denuclearization of Taiwan is a sufficiently existential problem to justify the modest risk of a leaker destroying a single PRC city.10

The next school is the “minimum deterrent” school, sometimes called the “minimum credible deterrent” school. This raises the threshold from the possibility of nuclear retaliation to the plausibility of a retaliation. Historically this seems to have been the favored posture of minor nuclear powers. It does not require that more than a handful of warheads reach their targets, or even strictly that any reach a target, only that the adversary finds it sufficiently uncertain as to their ability to defend against the attack. This one does still run into the issue, though, that Taiwan’s confidence may require a somewhat substantial number of warheads and delivery vehicles given the PRC’s defenses and likely tolerance for risk and damage in a war which the CPC views as existential.

The school of “assured retaliation” is where most nuclear powers seem to eventually wind up or want to wind up. The threshold for this school is that at least a few warheads must destroy their targets. Often this deterrent posture involves some sort of robust second-strike capability, such as ballistic missile submarines. In the face of PLA defenses, creating this capability strikes me as prohibitively expensive and time-consuming for Taiwan. Remember that the production of weapons-grade nuclear material is a major rate-limiting step. The faster you try to go, i.e. the more reactors or centrifuges you build, the harder it is to hide. Barring some novel enrichment technologies, this seems to create a real showstopper for Taiwan under this school of thought. I consider the “assured destruction” school entirely out of Taiwan’s reach and barely worth discussing.

Taiwanese leaders also have historically understood that nuclear weapons open them up to a greater risk of nuclear strikes. In the words of one of the Taiwanese scientists who first lobbied Chiang Kai-Shek to kill the program in the 60s,

If we look at it from the perspective of pure strategic power, Taiwan could not use nuclear weapons for offense purposes; on the contrary, by possessing such weapons, we increase the possibility of an attack initiated by our enemy because they would be alarmed. Taiwan is a small place with no room for maneuver if it was attacked with a nuclear weapon, unlike those countries with vast land, which, even if they were attacked first, would still have the opportunity to counterattack. They could rely on that potential power to maintain balance.

I am unsure whether the PRC would prefer to turn the entire island of Taiwan to glass than concede its independence, but there are asymmetries so profound that I am not confident even Taiwanese nuclear weapons can override them. This is a bleak picture for Taiwanese sovereignty. There are uncertainties here that hedge in Taiwan’s favor, of course. Perhaps they have done a good job covertly keeping the oven warm on weapons design or novel SNM production techniques. Perhaps I am seriously overrating the PRC’s will to take Taiwan, and even a very modest nuclear arsenal would be enough to secure Taiwanese sovereignty. Perhaps the economic uncertainties involved in going to war with a sizeable chunk of ASEAN are enough to keep Beijing from taking the jump.

However, I continue to believe that American extended deterrence is likely to be the only viable game in town, and our withdrawal would simply spell doom for Taiwanese independence. In fact, given how severe the costs of losing a war against the mainland would be, an abandoned Taiwan may find herself scrambling to make rapprochements with the mainland in the hopes of avoiding the destruction of war. The Hong Kong-ization of Taipei would be an inestimable tragedy for liberal values and would likely upend security architectures around the world as American unreliability is made manifest. The jungle may grow back regardless, but it is not in our interests to throw Brawndo on the vines.

About the Author

“George” is a scientist for a certain four-letter agency. The opinions expressed in this essay are his alone and do not reflect the views or policies of the United States Government nor any of her agencies or contractors. The information in this essay is derived solely and entirely from open sources and no endorsement of its completeness or accuracy is implied.

If you do, there’s a wealth of information out there, the main problem is just sorting the wheat from the chaff. There’s not really a good blog post to link to here yet. The CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues Deterrence 101 videos are fine.

This section draws heavily on David Albright and Andrea Stricker’s 2018 Taiwan’s Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand and Chapter 5 of Etel Solingen’s 2007 Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East. The 2018 work relies heavily on interviews with one Col. Chang Hsien-yi, Ph.D., who for reasons alluded to in Solingen’s work may not be an entirely reliable narrator of the events of the 1980s. He was intimately involved as a deputy director at INER, but some of his testimony conflicts with IAEA observations of the reactor at that time and I personally think he has his own motivations for playing up the level of readiness of the program. However, the level of detail in the 2018 book is substantial and makes for interesting reading if nothing else.

For more on TRR, see https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/207248/taiwan-research-reactor/.

I am not bothering to cite the entire background literature that I’m drawing on, but Narang’s 2022 Seeking The Bomb: Strategies of Nuclear Proliferation is quite good and worth highlighting.

Recent polling shows majority support in Taiwan for the acquisition of nuclear weapons, with 18% strongly approving and 42% approving somewhat. Curiously, this same poll found only 42% approval for an American nuclear response to a notional PRC nuclear use on Taiwan.

Although Narang himself says that he believes that in the absence of political consensus Taiwan would have adopted the “hard hedging” strategy described earlier in his book rather than hiding, I do not find this plausible in the current circumstances. For one, hard hedging involves open public debate and visible attempts to acquire breakout capabilities. This would create international political and economic pressure, it would provide a casus belli to the PRC, and it would likely rob Taiwan of much of the international support it might hope to receive even in an American vacuum. Taiwan runs all of these risks in a hiding scenario as well, but at least a hiding strategy requires Beijing to work to uncover the weapon program rather than gifting the knowledge up front.

https://satelliteobservation.net/2018/08/02/gf-11-how-do-you-say-kennen-in-chinese/ Some great open source work on PRC NTM. Also some work that @thrustwr.bsky.social has done in the open. For high quality open-source discussion of PLA conventional strike capabilities I refer the reader to the USAF China Aerospace Studies Institute’s publication series.

I leave out entirely here the thorny question of weapon sophistication and miniaturization but it is in my opinion highly relevant. A nuke is not just a nuke; a high yield, miniaturized thermonuclear weapon is qualitatively more threatening and more deterring than a low yield, cumbersome Fat Man or Little Boy type weapon.

They don’t get credit for identifying these 4 schools, but the summary in Keir Lieber and Daryl Press’ 2017 Myth of the Nuclear Revolution is concise and compelling. It is on my top 10 list for book recommendations for a number of reasons.

The PRC may also find the regretful American experience vis-à-vis the DPRK relevant here. The DPRK has not found it sufficient to acquire a single weapon capability, but rather used the breathing room from its threshold capability to more boldly pursue an advanced and large arsenal, which may be getting to the point where the US can’t confidently preempt or intercept each DPRK launch. It is also my personal opinion that the existential deterrence school gets fundamental aspects of deterrence wrong, at least when it comes to large powers. The stakes which might drive one to war against a nuclear power are likely to be so stark that you would tolerate the loss of a single city to achieve them. States have historically run and suffered much greater risks and costs in conventional wars. Put provocatively, why should we find it unbelievable that the PRC would trade Shenzhen for Taiwan if we also believe that we would trade Austin for Guam (or New York City for Berlin!)

Interesting! Small states around the world must now feverishly and seriously consider nuclear options as the US nuke umbrella appears to be closing. IMO it was the primary rationale behind non proliferation. Trump has destabilized the post war security architecture.

What's your opinion about the capabilities and willingness of Eastern European NATO countries to gain nuclear weapons or at least covertly start bomb research and acquire possible delivery systems?