Bombing Because You Can: The Easter Offensive and Operation Linebacker I

Part III: The Rivalry between Close Air Support and Strategic Bombing

“The bastards have never been bombed. They’re going to be bombed this time.” -President Richard Nixon, April 4, 1972

In the spring of 1972, the Vietnam War reached a dramatic turning point. North Vietnam launched its largest offensive to date, testing the resilience of South Vietnam's forces and the credibility of the U.S. program of “Vietnamization.” With almost all American ground troops withdrawn, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) found itself overwhelmed by a ferocious, Soviet-equipped assault across multiple fronts. The Pentagon, caught off guard, scrambled to respond, and President Nixon, unwilling to concede defeat, unleashed a bombing campaign unlike anything seen before. Dubbed Operation Linebacker I, these operations marked a decisive moment in the war, blending brute airpower with strategic precision. Could air dominance alone compel the North Vietnamese to negotiate “peace with honor”? Or would it merely prolong a conflict already drenched in sacrifice and controversy?

The United States had undertaken an extensive bombing campaign under President Johnson called Operation Rolling Thunder against North Vietnam from 1965 to 1968 but had failed to compel the communist party into negotiations. Waffling between two different strategies, the Air Force and Navy bombed hundreds of targets, costing at least 922 aircraft in addition to 1,000 airmen killed, wounded, or captured. Johnson finally suspended the bombing on November 2, 1968, three days before the presidential election that he opted not to run in. Richard Milhous Nixon achieved one of the most remarkable comebacks in American political history, emerging victorious in a fiercely contested three-way election and assuming office at a moment when the nation appeared on the brink of chaos.

(Note you can read Part II about Operation Rolling Thunder here and Part I about the strategic bombing effort in World War II here)

Nixon was determined not to be his predecessor. He had campaigned to end American involvement in the war and achieve what he called “peace with honor.” But for the first two and a half years of his presidency, he had been frustrated by events within and beyond his control. Military actions, such as launching operations in Cambodia and secretly bombing Laos, intensified the anti-war movement and provoked congressional backlash, further constraining his options in Vietnam. Meanwhile, political strategies such as opening relations with China and pursuing détente with the Soviet Union failed to alter North Vietnam’s negotiating stance, which remained the complete withdrawal of U.S. troops and the overthrow of the South Vietnamese government, which was a nonstarter for the Nixon administration after so much American sacrifice.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) maintained its original role in an official advisory capacity, while the Air Force and Navy delivered air support. By mid-1972, fewer than 70,000 U.S. personnel remained in the country, the majority serving as advisors or trainers.1 Vietnamization produced an ARVN that had 11 infantry divisions, 58 artillery battalions, and a host of irregular and special forces battalions totaling nearly 550,000 men.2 Even still, the withdrawal of U.S. combat troops had left the ARVN spread dangerously thin. For instance, in I Corps (the northern part of the country), 80,000 U.S. troops had been replaced by only 25,000 ARVN troops, now tasked with holding the same territory.3 This was coupled with the fact that the ARVN was focused on counterinsurgency and pacification for much of its existence rather than conventional warfare, leaving it ill-prepared to defend against a large, combined arms offensive. To move along the program faster, equipment and supplies flooded South Vietnam to outfit ARVN units, but the quality of units was all over the place.4 The Marine, Airborne, and Ranger units were all crack outfits but in limited numbers. The ARVN 3rd Division, for example, which had taken over security in the Northern part of the country, arguably the most critical terrain in the defense against an invasion, was poorly led and trained.5

The North Vietnamese strategy is worth examining. The Communist party leadership in Hanoi never strode away from the belief that only “decisive victory” would bring the conflict to an end, even when large numbers of U.S. combat troops were deployed to South Vietnam.6 While U.S. troops were deployed, decisive victory was defined as “inflicting heavy casualties on US forces, destroying a major portion of the ARVN in order to render that army impotent, and inciting a ‘general offensive–general insurrection’ in the cities and rural areas.”7 While the actual implementation of these strategies, the Tet Offensive, and a series of other offensives launched in late 1968 and 1969 did not achieve decisive military victory, it did undermine the depth of the US commitment to Vietnam, which by 1972 was in its nadir.8 Another argument made for its offensive in 1972 is that North Vietnam sought to influence the 1972 presidential election.9 By launching their largest offensive to date, the North Vietnamese aimed to force the United States into concessions at the negotiating table, solidify their strategic position, and hasten the end of a war they believed could only conclude on their terms.

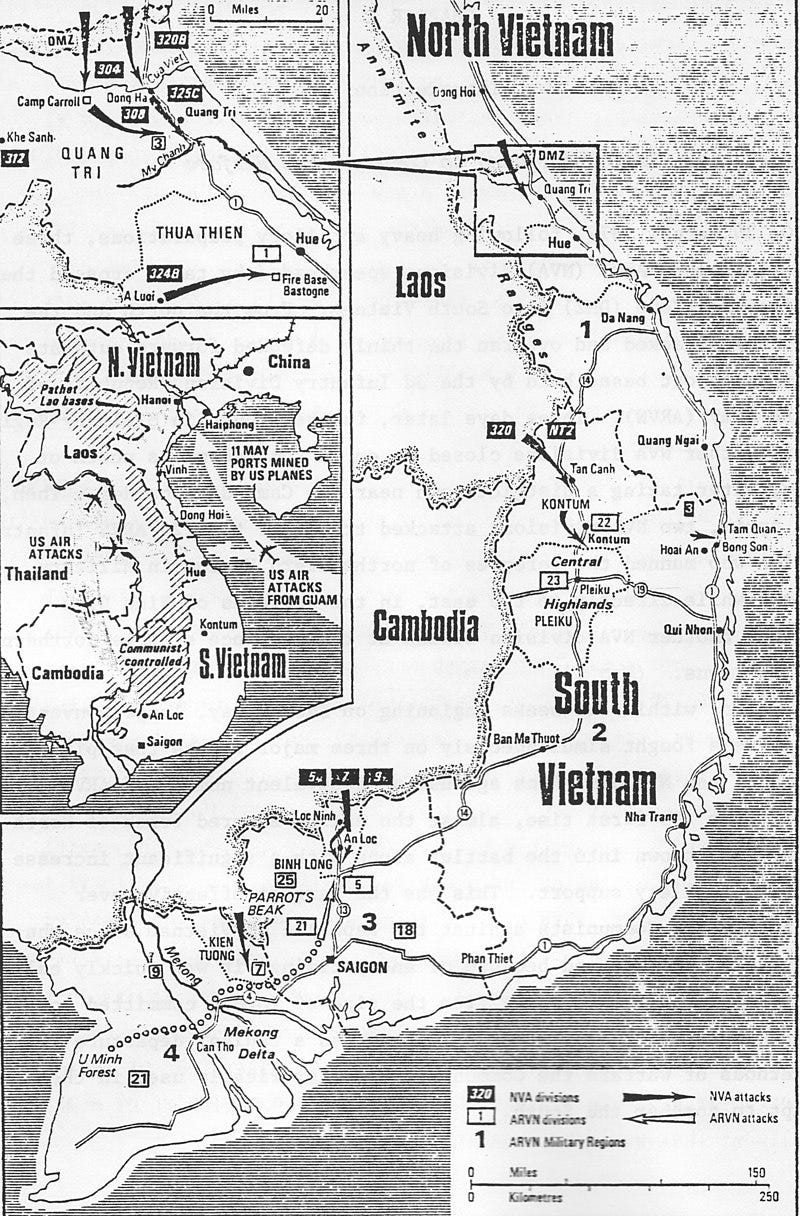

On March 30, 1972, North Vietnam began its offensive with a massive artillery bombardment, lobbing 4,000 artillery rounds at the string of firebases along the border.10 One historian observed that the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) “dispensed with clever maneuvers and simply charged across the DMZ,” a move most analysts dismissed at the time as impossible.11 The North Vietnamese committed nearly their entire ground force, which would prove to be the “ultimate test of Vietnamization.”12 14 of their 15 divisions and 26 separate regiments, totaling an estimated 130,000 to 150,000 troops.13 These forces had the most up-to-date Soviet weaponry, including 1,200 tanks and armored fighting vehicles, long-range artillery, modern air defense systems, and anti-tank-guided missiles. The NVA launched attacks along three primary axes: the main offensive across the DMZ in the northern part of the country, a secondary assault from Cambodia toward Saigon in the southern part, and a third advance from Laos and Cambodia into the Central Highlands. The CIA concluded that it was a “relatively straightforward conventional invasion.”14 Whether driven by hubris or political pressure, this was a complete departure from the North's concept of guerilla warfare, instead going for a knockout blow that would decisively crush the South once and for all.

The American response in the first few weeks was hampered by confusion and indecisiveness. The Pentagon was not overly concerned; the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam and the Commander of MACV, General Creighton Abrams, were out of the country. This isn’t surprising; Nixon and Kissinger had rerouted the entire foreign policy decision-making process to the National Security Council, creating a habit where the bureaucrats waited around for orders rather than taking the initiative. With the deployment of U.S. ground troops out of the question, Nixon turned to air power as a solution. He boasted, “The bastards have never been bombed. They’re going to be bombed this time.”15

As American air power began to assemble, events on the ground quickly began to spiral out of control. The 304th and 308th divisions from the NVA, supported by more than 100 tanks, quickly bypassed or captured firebases occupied by ARVN troops along the DMZ and rushed towards the sea. Within a day, the ARVN 3rd Division was ordered to withdraw, rapidly becoming a full retreat. The advance had been timed to coincide with the seasonal monsoon, hampering U.S. air support for the first two weeks of the offensive, allowing the NVA’s mechanized forces to roam freely, leading Nixon’s National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger to quip, “We must have the world’s worst air force.”16

It wasn’t just near the DMZ that ARVN units were retreating. An Lộc, the capital of Bình Long Province just under 90 miles from Saigon, was surrounded and besieged by 3 Divisions while the NVA’s 320th Division was trying to bludgeon their way into the Central Highlands. The South Vietnamese commanders in the area were so terrified and indecisive that John Paul Vann, the director of the U.S. Second Regional Assistance Group, gave up all pretext of South Vietnamese command, taking over himself and openly issuing orders to ARVN units even though he was American and a civilian.17 He stated of the ARVN, “the sons of bitches will have to fight or die.”18 It appeared that Vietnamization was on the verge of crumbling.

With the weather hampering air support in the South, Nixon was determined to unleash a bombing campaign on the North like never before. However, the DoD stalled, wary of being caught up in another one of Nixon’s schemes. Their concerns were justified, especially in light of the public outrage sparked by the incursion into Cambodia in April 1970 and the revelation of secret bombings there, exposed by The New York Times a year earlier. In a classic Nixon tirade, he dismissed the initial bombing plan presented by the Joint Chiefs of Staff as “half-assed,” “inadequate,” and “disgraceful.”19

The primary debate among American policymakers centered on whether to focus on a strategic bombing campaign against the North or prioritize providing air support for operations in the South. From Nixon’s perspective, the military effectiveness of a strategic bombing campaign was less of a priority than the need to address what he described as dealing with the “political problem with the Russians” and the importance of “sending a message” to North Vietnam.20 In some ways, that view was no different from Johnson’s, but he didn’t want any limits on targeting. Kissinger was worried that an extensive air campaign against the North would get in the way of providing air support to the ARVN, which, in his view, was the overriding priority.21 Abrams concurred, believing that airstrikes in the North should only be carried out if they could hit “real pay dirt.”22 Defense Secretary Melvin Laird was against any action that the Soviets or Chinese might view as an escalation.23 Regardless of the divided opinions in the cabinet, Nixon was the president; it was his call, and he wanted “an intense no-holds-barred air and naval campaign against the North.”24 However, almost all of the command-and-control issues from Rolling Thunder persisted. There was no overall theatre commander and an Air Force study found that “U.S. air resources conducted relatively independent air operations against separate geographical sections of North Vietnam.”25 This lack of centralized coordination meant that, despite Nixon’s desire for an unrestrained and impactful air campaign, the effectiveness of U.S. air power was undermined by the same structural inefficiencies that had plagued earlier efforts, diluting its strategic potential.

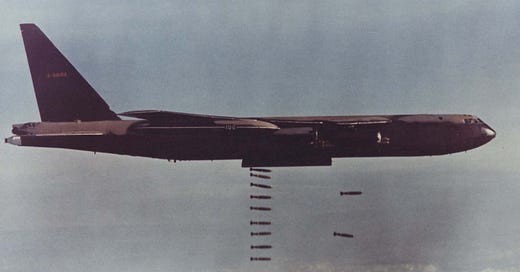

Operation Linebacker I got underway a week and a half after the NVA offensive started. The first large-scale raid took place on April 10, with 12 B-52s, supported by 53 F-4 Phantoms and F-105 Thunderchiefs, targeting petroleum storage facilities.26 Two days later, Nixon informed Kissinger of his decision to launch a more extensive bombing campaign, including strikes on Hanoi and Haiphong. On April 13, 18 B-52s attacked the Bai Thuong Air Base near Thanh Hóa. By mid-April, nearly all North Vietnam was opened to bombing raids for the first time in over three years. While the convoluted chain of command posed challenges, Air Force and Navy commanders, along with their pilots, embraced Nixon’s approach, which contrasted sharply with President Johnson’s. Nixon granted operational planning authority to local commanders and relaxed the restrictive targeting rules that had hampered Operation Rolling Thunder. Lieutenant General Dave Palmer would remark, “Linebacker was not Rolling Thunder - it was war.”27

Indeed, it was war, and this was a different American Air Force and Navy than the ones that ran Operation Rolling Thunder. Laser-guided bombs, advanced electronic warfare equipment, and revamped tactics “threw North Vietnam's air defenses into complete disarray.”28 During the April 10 attack, North Vietnamese defenders not only failed to engage the B-52s, but their radars were so disrupted by American electronic jamming that they couldn't even confirm the B-52s' involvement until the following day when bomb damage assessment teams analyzed the craters.29 By the end of May, American aircraft successfully destroyed 13 bridges along the rail lines connecting Hanoi to the Chinese border. Four key bridges between Hanoi and Haiphong, including the infamous Thanh Hóa Bridge, were also demolished with laser-guided bombs. Several others along the rail line heading south toward the DMZ were also taken out.

Despite the early successes of Linebacker I, the situation on the ground had become dire: Quang Tri City had fallen; the road to Hue lay open, An Loc was still under siege, and Kontum in the Central Highlands faced imminent threat. On May 2, General Abrams visited Saigon to have a “come-to-Jesus” meeting with South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. All the chronic issues of the ARVN, corruption, ineffectual leadership, and political cronyism, were directly contributing to the current situation. Abrams gave Thiệu a list of ARVN generals he wanted to be fired and told him on no uncertain terms that “all that had been accomplished over the last four years was now at stake” and “it was the effectiveness of his field commanders that would determine the outcome—either winning all or losing all.”30 The Nixon administration was facing its own “come-to-Jesus” moment as South Vietnam appeared on the brink of collapse just seven months before the presidential election. During a National Security Council meeting on May 8, Nixon emphasized the need for “cold-blooded analysis,” declaring that “the diplomatic track is totally blocked” unless they could help the ARVN win.31

As grim as the situation looked, the NVA were quickly reaching what the famous military theorist Carl von Clausewitz called the “culmination point.”32 For example, the 4,400 artillery rounds fired by NVA forces in the last days of April in Quang Tri Province were countered by nearly 8,000 rounds fired from U.S. Navy ships offshore.33 The Navy and Air Force had amassed nearly 800 aircraft providing daily air support, inflicting severe punishment on the NVA.34 Throughout May, nearly 1,000 tactical air sorties and 75 B-52 strikes were carried out daily, consuming ammunition and ordnance so rapidly that Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Admiral Thomas Moorer voiced concerns about the risk of completely depleting supplies.35 North Vietnamese commanders, accustomed to operating in small, independent units conducting guerrilla warfare, now faced the challenge of managing a larger chain of command, integrating new tactics, and launching conventional attacks in open terrain under heavy air attack. One analysis concluded that the operational competence of the NVA was “poor” and “unimaginative.”36 The American military, for one, welcomed this development. The senior U.S. adviser overseeing the defense of An Lộc, Lt. General James Hollingsworth stated,

Once the Communists decided to take An Loc, and I could get a handful of soldiers to hold and a lot of American advisers to keep them from running off, that's all I needed. Hold them and I'll kill them with air power; give me something to bomb and I’ll win.37

The generals weren’t alone in sensing a rare opportunity. Kissinger remarked to Nixon during a conversation,

Mr. President, if we can hold the line, as long as it doesn’t mean the loss of Hue and Da Nang, if we can hold the line then we’ve got them out in the open where they are concentrated; there’s no jungle there. And we are going to grind them down.38

This convergence of strategic advantage and overwhelming firepower marked a pivotal moment in the Easter Offensive, where the United States aimed to turn the tide not just through ground resistance but by leveraging its unmatched dominance in the skies. American air power played the most prominent role in the siege of An Loc and a series of ARVN counterattacks to retake Quang Tri province. The ARVN had delayed the NVA attacks along the southern axis just long enough to organize a defense of the vital town. The defenders had dug into the town center, roughly a rectangular perimeter measuring 2 kilometers by 1 kilometer.39 The first ground assault on An Lộc began on April 13. The ARVN defenders endured a relentless fifteen-hour artillery barrage of 7,000 rounds, followed by an attack involving two regiments of infantry and approximately two dozen T-54 tanks.40 As the NVA advanced through the narrow streets, they were swiftly ambushed from the flanks by small arms fire and handheld anti-tank weapons, forcing them to retreat. Further assaults ensued, and by April 15, the northern part of the town had fallen under NVA control, even though a B-52 strike had taken out four tanks and 100 infantrymen in the attacking force.41 The situation seemed hopeless, but shell by shell, rocket by rocket, and bomb by bomb, American firepower began to tell. Every NVA attack was answered with a symphony of destruction: B-52 squadrons raining down 105 tons of bombs, F-4 Phantoms striking with laser-guided munitions, Cobra helicopters unleashing rockets, and AC-130 gunships picking off tanks with pinpoint shots from their modified 105-millimeter cannons.

May 11 was the day of crisis as the NVA launched the most significant attack to date in the battle. The situation became so dire that the forward air controllers turned no aircraft away, regardless of ordnance load.42 B-52 Arc Light strikes, conducted around the clock every 50 minutes, were brought astonishingly close—within just 650 yards—of the ARVN perimeter.43 At one critical moment, the 36th Ranger Battalion was in danger of being overrun, with the only available support being an F-4 Phantom loaded with 500-pound “Daisy Cutter” bombs, typically used for clearing landing zones.44 The forward air controller directed the aircraft to drop the bombs just 200 yards (2 football field lengths) ahead of the Rangers’ positions, and the massive blasts successfully broke up the NVA assault. At another moment that day, Lt Colonel Gordon Weed made a low-level pass in his A-37 Dragonfly through heavy enemy antiaircraft fire to neutralize a T-54 tank firing directly into the 5th ARVN Division's command post.45 On his first pass, a 250-pound bomb scored a direct hit on the tank’s turret, but it failed to detonate and bounced right off. Sensing desperation through the forward air controller on the other end of the radio, Weed didn’t hesitate and came around for another pass, braving a fusillade of 37-mm and .51-caliber ground fire, delivering another precision strike. This time, the bomb exploded, destroying the tank and forcing the supporting infantry to retreat.

On May 11 alone, there were 300 air support sorties and 30 B-52 strikes, dropping nearly 3500 tons of explosives to support the besieged defenders.46 The following four days saw another 1000 sorties from American and South Vietnamese aircraft.47 The air attacks were so ferocious that by late May, the crisis had passed, but An Loc had been turned into a “charcoal house.”48 It was only a month later, on June 19, that the siege officially came to a close. It was a sobering victory; the NVA had suffered at least 25,000 casualties, but An Loc was yet another town that seemingly had to be destroyed in order to be saved. Colonel William “Bill” Miller, the senior adviser to the 5th ARVN Division, later testified before the House Armed Services Committee, stating that, in his view, the ARVN had not truly won at An Loc but had simply managed to avoid defeat, thanks mainly to their advisers and the support of American air power.49

With An Loc saved, the fighting shifted back north where the Easter Offensive had begun. Abrams’ “come-to-Jesus” meeting with President Thiệu had spurred results. General Ngô Quang Trưởng, arguably the ARVN’s best general, had been tasked with retaking Quang Tri Province. Holding An Loc and Kontum freed up the Marine and Airborne divisions, the two best in the ARVN army. Truong opted for a much more methodical offensive plan, using American air strikes as a battering ram before his troops assaulted head-on. He called this plan “Loi Phong” which translated to “Thunder Hurricane.” As he further described

In essence, was a sustained offensive by fire conducted on a large scale. The program scheduled the concentrated use of all available kinds of firepower, artillery, tactical air, Arc Light strikes, naval gunfire for each wave of attack and with enough intensity as to completely destroy every worthwhile target detected.50

By this point, the coordination between units on the ground and in the air was much better. Truong established a Fire Support Coordination Center in I Corps and pushed forward air controllers to frontline units to partner with American advisors who could talk to the influx of English-speaking-only pilots flying air support missions.51 The counteroffensive kicked off on June 28, and by July 8, the ARVN paratroopers had reached the city’s outskirts. However, Truong quickly realized that “the enemy's determination was all too clear; he planned to hold Quang Tri City to the last man.”52 The battle was vicious, devolving into what one historian called “an urban Dien Bien Phu without rationale,” creating a “vortex of violence sucking in men and shells, and spinning out corpses and the maimed.”53 Possession of the city was entirely symbolic.

The battle dragged into September, with the NVA rotating six different divisions through the city to hold it.54 But in doing so, they proved to be “lucrative targets for the combined fires of artillery, tactical air, and B-52s.”55 A final offensive launched on September 8 took complete control of the city when ARVN Marines raised the South Vietnamese flag over the ancient citadel in the center of the city. U.S. aircraft flew nearly 6,000 sorties that month to support Truong’s counteroffensive.56 Despite challenging weather at the outset, the tactical campaign from April through June saw 18,000 sorties flown.57 The Air Force accounted for 45% of the missions, with the Navy and Marine Corps contributing 30%, and the South Vietnamese forces completing 25%. Additionally, B-52 bombers from Strategic Air Command conducted 2,700 sorties targeting the northern provinces, delivering 57,000 tons of ordnance.58

Despite the victory, there were clear limits to the use of air power in the Quang Tri counteroffensive. This is because the NVA had more or less been positioned in a static defensive setup using the most favorable terrain possible. Such stationary forces, mainly when not actively engaged in combat, demand significantly fewer supplies than units engaged in offensive operations or conducting mobile defenses.59 It’s not a coincidence that the battle for the city dragged on for two and a half months, even as the number of sorties and ordnance used peaked. The ARVN sustained an equivalent number of casualties during the battle from April and May as they had from June to September, despite the latter period occurring with a massive amount of air support.

There is an argument to be had that correlation does not equal causation. Still, even Phil Haun and Colin Jackson, strong proponents of the critical role U.S. air support played in the Easter Offensive, acknowledged that “Air alone, even in immense volumes, could not root out the NVA defenders of the Quang Tri Citadel if the ARVN forces were unwilling to fight and die on the ground.”60 The ARVN did stand their ground and fight, slugging it out with the best the North Vietnamese could throw at them and came out on top. American historiography of the war has regularly criticized the performance of the ARVN but there was irony in the fact that, “the biggest battle of the Vietnam War was won not by U.S. ground troops but by a weak ally supported by a handful of U.S. military advisers and air liaison officers.”61 In the end, the Quang Tri counteroffensive was a testament to the ARVN's resilience, proving that with determination, strategic support, and airpower, even a “weak ally” could achieve what many thought impossible.

Throughout all of the fighting in the South, Linebacker I didn’t let up at all. In June, B-52 raids were being launched so frequently that bombs were being dropped on targets every 48 minutes.62 It was having its intended effect, as North Vietnamese military officials admitted,

Almost all of the important bridges on the railroad lines and on the road network were knocked out. Ground transportation became difficult. Coastal and river transportation was blocked. The volume of supplies shipped across the Gianh River to the battlefields in South Vietnam fell to only a few thousand tons per month.63

North Vietnam’s import capacity was reduced by 80%, overland imports from China dropped from 160,000 tons a month to 30,000 tons a month, and replacement troops infiltrating the South were reduced by 75%.64 The bombing effort undoubtedly contributed to stalling the momentum of the North’s offensive. On June 20, the North agreed to return to the negotiating table in July, conceding that the South would not collapse. The bombing continued even while negotiations were occurring in Paris and came to a stop in October.

In Paris, where peace talks had dragged on for years, the bombing campaign introduced a new urgency. In Paris, Kissinger observed that each setback on the battlefield or bombing mission made North Vietnam more reasonable in negotiations, perhaps the clearest indicator of Linebacker’s success. For Nixon, Linebacker I was not just about military gains—it was about forcing North Vietnam to the table on American terms or at least creating the appearance of progress ahead of the November election. However, Nixon was reluctant to end the war outright before the election, viewing Vietnam as a key issue where he held a significant electoral advantage over his Democratic challenger, George McGovern, who had pledged to withdraw all U.S. troops and end the war within three months, regardless of the terms.65 Nixon viewed that proposition more or less as surrender and believed the public would also, hence why he stalled. The Easter Offensive and Linebacker I had bought a window of opportunity to end the war, but politics had gotten in the way, and that would ultimately necessitate an entirely new operation in December.

Did Operation Linebacker I successfully force the North Vietnamese to sign the Paris Peace Accords? At the heart of the debate is the question of how much importance should be placed on the air campaign in the North compared to the air support provided in the South. The Airpower historian Mark Clodfelter wrote, “Although Linebacker was not solely responsible for Hanoi’s negotiating reversal, Nixon could not have gained Communist concessions without it.”66 An Air Force study conducted in 1975 concluded,

Interdiction operations were a primary factor in the decision of NVA leaders to abandon their hope of an outright military victory and to step up their diplomatic efforts in order to achieve their goals through political means.67

General John Vogt, deputy commander of MACV during the Easter Offensive, took it one step further, saying emphatically, “After Linebacker I, the enemy was suing for peace. They were hurt real bad. Most of the major targets had been obliterated in the North…and they were ready to conclude an agreement.”68 In fact, Vogt later stated that Kissinger and Nixon threw the towel in too early, and that Linebacker I should have continued unabated. These assessments suggest that while Operation Linebacker I alone did not compel North Vietnam to sign the Paris Peace Accords, the air campaign significantly shaped Hanoi's strategic calculations, shifting from pursuing a military victory to prioritizing diplomatic negotiations to achieve their objectives.

Other scholars argue that the strategic bombing campaign had little to no impact; instead, close air support by tactical aircraft, arc light missions from B-52s, and helicopter gunships coordinated by American advisors and air force liaison officers on the ground allowed the ARVN to recover, get back in the fight, and inflict devastating losses on the NVA in a conventional battle.69 Phil Haun and Colin Jackson make the most compelling case for this argument summarizing,

Without U.S. air support, it is hard to imagine a successful ARVN defense in South Vietnam. With it, the defeat of the Easter Offensive was possible, and that outcome left the North Vietnamese with few alternatives to a negotiated settlement. This, in turn, brought the North Vietnamese to accept the "peace with honor" terms necessary to prompt the United States to decide to withdraw its forces from Vietnam. It was not, however, Linebacker I's air interdiction campaign in North Vietnam that was decisive; rather, it was U.S. air power's direct attack of the NVA fielded forces and forward supplies in the south that allowed the ARVN to hold at An Loc and Kontum and that turned the tide at Quang Tri.70

Stripping away the metrics—sorties flown, bombs dropped, and targets hit—Linebacker was undeniably successful if its sole objective was to return North Vietnam to the negotiating table. However, its success was far more limited if the goal was to secure lasting peace.

In my view, the single most decisive factor did not lie with any American decision but rather the North Vietnamese decision to launch a conventional offensive. As Robert Pape observed, “Hanoi had changed from a guerrilla strategy, which was essentially immune to air power, to a conventional offensive strategy, which was highly vulnerable to air interdiction.”71 Whether this was driven by hubris or the political need to achieve a “decisive victory,” Hanoi effectively backed itself into a corner. This decision aligned perfectly with the American way of war, which, since the Civil War, has relied on overwhelming firepower. In this case, however, that firepower was predominantly delivered from the air rather than the ground.

However, the campaign also underscored the limitations of air power. Despite the massive devastation caused by the 155,548 tons of bombs dropped during Linebacker I, North Vietnam's leadership remained steadfast in their pursuit of reunifying the country under their control.72 Linebacker I was a tactical success for the United States but a strategic question mark. It prolonged the war and gave Nixon the political breathing room he needed, but it could not resolve the fundamental contradictions of Vietnamization or the fragility of the South Vietnamese state. How many more communist offensives would Congress be willing to counter and fund? Were the aircraft of the United States Military now the permanent guarantor of South Vietnam's security? Would the United States drop hundreds of thousands of tons of bombs on the same bridges, warehouses, and factories every single time the NVA crossed the DMZ? While Linebacker I and the air support during the Easter Offensive demonstrated the effectiveness of air power in achieving short-term objectives and winning conventional battles, it left unanswered the more significant questions of whether sustained American intervention could secure long-term peace or if South Vietnam could ever stand on its own without constant U.S. support.

As the negotiations dragged on, Nixon ordered an even more intense bombing campaign—Linebacker II, also known as the Christmas Bombing—later that year, which will be covered in the next part of the Airpower/strategic bombing series. Yet even the heaviest bombardments could not erase the enduring reality: the Vietnam War was a conflict of wills as much as it was a clash of arms, and in that contest, the limits of American power were becoming increasingly apparent.

References

Clodfelter, Mark, 2006. The Limits of Airpower: The American Bombing of North Vietnam. New York: Free Press.

Dallek, Robert. 2007. Nixon and Kissinger Partner in Power. New York: HarperCollins.

II, Merle L. Pribbenow. 2008. "General Võ Nguyên Giáp and the Mysterious Evolution of the Plan for the 1968 Tết Offensive." Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 1-33.

II, Merle L. Pribbenow. 2001. "Rolling Thunder and Linebacker Campaigns: The North Vietnamese View." The Journal of American-East Asian Relations Vol. 10, No. 3/4 197-210.

Jackson, Phil Haun and Colin. 2016. "Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II." International Security, Vol. 40, No. 3 139-178.

Karnow, Stanley. 1983. Vietnam: A History. New York: Penguin.

Keefer, John M. Carland and Edward C. 2010. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume VIII, Vietnam, January–October 1972. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Miller, Sergio. 2021. No Wider War: A History of the Vietnam War Volume 2: 1965–75. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Nalty, Bernard C. 2001 Air War over South Vietnam 1968–1975. Washington: Air Force History and Museums Program.

Pape, Robert A. 1996. Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sheehan, Neil. 1989. A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and the American Tragedy in Vietnam. New York: Vintage.

Sorley, Lewis. 1999. A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harcourt Publishing Company.

Truong, Ngo Quang. 1980. The Easter Offensive of 1972. Washington: U.S. Army Center of Military History

Wilbanks, James. 1993. Thiet Giap! The Battle of An Loc, April 1972. Fort Leavenworth: Army University Press.

Neil Sheehan, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and The American Tragedy in Vietnam (New York: Vintage, 1989), 751.

Lewis Sorley, A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam (New York: Harcourt Publishing Company, 1999), 306.

Phil Haun and Colin Jackson. "Breaker of Armies: Air Power in the Easter Offensive and the Myth of Linebacker I and II." International Security, Vol. 40, No. 3 (2016): 149.

By the beginning of 1972, there were less than 100,000 US soldiers in South Vietnam only 7,000 of which were deemed for combat.

Only the 2nd ARVN Regiment of the 3rd Division was considered reliable; the 56th and 57th were made up of unwilling volunteers (Miller, 298).

Merle L. Pribbenow II "General Võ Nguyên Giáp and the Mysterious Evolution of the Plan for the 1968 Tết Offensive." Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (2008): 1-33.

Ibid., 10-11.

Ibid., 24-25.

Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Penguin, 1983), 654.

Sorely, 321.

Sergio Miller, No Wider War: A History of the Vietnam War Volume 2: 1965–75 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021), 298.

Haun and Jackson, 149.

Disagreements persist regarding the number of NVA troops involved in the Easter Offensive. Haun and Jackson estimate the figure to be 130,000 to 150,000, while the Air Force's after-action report suggests it was closer to 200,000.

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume VIII, Vietnam, January–October 1972. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2010), Document 73. Cited as FRUS with Volume and Document Number.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 59.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 47.

Vann’s career in Vietnam is well chronicled in Neil Sheehan’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Bright Shining Lie, see p. 756-790 for his actions during the Easter Offensive.

Sheehan, 764.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 52.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 74.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 74.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 74.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 68.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 67.

Mark Clodfelter, The Limits of Airpower: The American Bombing of North Vietnam (New York: Free Press, 2006), 164.

This marked the introduction of laser-guided “smart” bombs.

General Dave Palmer quoted by Sorely, 327.

Merle L. Pribbenow II, "Rolling Thunder and Linebacker Campaigns: The North Vietnamese View." The Journal of American-East Asian Relations Vol. 10, No. 3/4 (2001): 206.

Ibid., 206.

Haun and Jackson, 153.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 111.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 131.

The culmination point in military strategy refers to the stage in a campaign or operation where a force can no longer sustain its offensive due to diminishing resources, morale, or momentum, making further advances untenable. At this point, the attacker risks becoming overextended and vulnerable to counterattack, shifting the initiative to the defender.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 107.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 154.

Sergio Miller, No Wider War: A History of the Vietnam War Volume 2: 1965–75 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing. 2021), 324.

Gen. James Hollingsworth, quoted by James Wilbanks in Thiet Giap! The Battle of An Loc, April 1972 (Fort Leavenworth: Army University Press, 1993), 22.

FRUS, Vol VIII, Document 57.

Haun and Jackson, 156.

Haun and Jackson, 157.

Bernard C. Nalty, Air War over South Vietnam 1968–1975 (Washington, Air Force History and Museums Program, 2001), 386-387.

Wilbanks, 49.

Haun and Jackson, 158.

Wilbanks, 50.

Wilbanks, 51.

Haun and Jackson, 158.

Naylor, 396.

Haun and Jackson, 158.

Wilbanks, 61-62

Ngo Quang Truong, The Easter Offensive of 1972 (Washington: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980), 54.

Haun and Jackson, 167.

Truong, 67.

Miller, 309-310.

Truong, 69.

Truong, 70.

Truong, 70-71.

Nalty, 369.

Nalty., 370.

Daryl G. Press argues about the limits of airpower against defensive positions in “The Myth of Air Power in the Persian Gulf War and the Future of Warfare.” International Security 26, no. 2 (2001): 40-42.

Haun and Jackson, 170.

Haun and Jackson, 173.

Robert Dallek, Nixon and Kissinger Partner in Power (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 403.

Pribbenow II, "Rolling Thunder and Linebacker Campaigns," 208.

Robert A. Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 200.

Dallek, 414-415.

Clodfelter, 174.

Clodfelter, 176.

Clodfelter, 176.

Haun and Jackson, 138.

Haun and Jackson, 171.

Pape, 209.

Clodfelter, 176.

Excellent. Detailed and a very interesting indeed. Filled in a lot of blanks for me regards the later stages of the war. Thank you 👍

Both Mao and Giáp write about how the Third Phase of people’s war will include a transition from guerrilla war to conventional war, but they don’t offer much by way of specific guidance as to exactly when and how that transition comes about.