The Death of the Soldier and the State

Los Angeles, Marines, and the Making of a Partisan Military

The past week has been a striking one for American civil-military relations. The federalization of the California National Guard over the objections of the elected governor, something not seen since 1965, the “deployment” of a Marine infantry battalion to Los Angeles for the first time since 1992, and a presidential address that may rank among the most openly partisan ever delivered with uniformed troops cheering in the background, all mark serious breaches of long-standing norms.1 The performative militarism, the partisan signaling, and the deafening silence from military leadership are deeply alarming. These are not isolated events. They are symptoms of a larger trend that has occurred over many years: the slow but deliberate politicization of the military, carried out under the banner of professionalism but made possible by both political opportunism and a military culture that has grown dangerously detached from its own civic responsibilities.

In the American political tradition, the military is meant to exist outside the arena of partisan politics, loyal only to the Constitution and subordinate to civilian authority. This idea, what Samuel Huntington famously termed “objective control,” rests on the notion of a military that is apolitical, professional, and autonomous in its sphere.2 The Soldier and the State has been something of a lodestar for the American military, guiding its views on civil-military relations for generations. Major General William Rapp, a former commandant of West Point and the U.S. Army War College, wrote a decade ago that “Huntington’s 1957 The Soldier and the State has defined civil-military relations for generations of military professionals. Soldiers have been raised on Huntingtonian logic and the separation of spheres of influence since their time as junior lieutenants.”3 Huntington and his book remain popular within military circles essentially because his theories offer a convenient framework that absolves the military of broader civic or political responsibility. “Objective control” draws a very clear boundary between the military and the civilian world: the military stays apolitical and professional, while civilians handle policy and politics.4 This in turn, required “the separation of political from military considerations during the professional officer's analytical processes.”5 This division is appealing because it allows the military to focus narrowly on preparing for and executing war, without getting entangled in the realities of democratic accountability, public legitimacy, or institutional introspection.6

In practice, this has meant that the officer corps can claim neutrality while sidestepping difficult questions about how military force is used, whom it serves, or how it is perceived.7 This has played out regularly when debating military strategy during wartime or civilian laws that affect the military, which is usually fine within the context. However, Huntington’s framework, in essence, gives the military license to view itself as a self-contained technocratic elite, concerned only with operational competence and strategic execution, rather than the political context or moral consequences of its actions at home or abroad.8 That detachment is not just theoretical; it shapes real-world behavior, from silence in the face of politicization to a reflexive defensiveness when confronted with any sort of civilian critique.9

In theory, the military is a tool of the state, not a faction within it. However, this clean separation assumes a level of clarity and restraint that rarely exists in practice, as many scholars have noted over the last decade.10 The modern military officer is instructed to refrain from engaging in politics, avoid expressing partisan views, and adhere to the chain of command. But they are also expected to navigate increasingly politicized environments, from cable news cycles to domestic deployments, without any preparation, institutional vocabulary, or sense of how power operates in a democratic society. The modern American officer corps is trained to think in terms of loyalty, duty, and mission, but not in terms of institutions, norms, or public legitimacy. This is a dangerous form of professional thought: the refusal to engage with the political context in which military force operates leads to a kind of moral paralysis when that context turns hostile.11 So when troops are used as set dressing for a campaign event or sent on vaguely defined missions to police American cities, the reaction from much of the officer corps is not outrage but confusion. They don’t know what to do because they were never taught to ask what it means.

And this is the core of the problem. At its most basic level, the Huntington framework is a simple bargain. The military maintains its “neutrality” in politics, refrains from public commentary, and remains institutionally silent on partisan matters. In return, civilian leadership grants it wide latitude to manage its internal affairs, including doctrine, promotions, and professional standards. However, that bargain only works under particular conditions: a shared understanding of boundaries, mutual respect for institutional roles, and a stable political environment that is capable of honoring the deal. Today, those conditions are breaking down at a rapid pace. Civilian leaders increasingly pull the military into politically charged situations, whether through public appearances, domestic deployments, or cultural flashpoints, while military leaders, clinging to a hollow version of "apolitical professionalism," pretend they can navigate these waters without consequence. The result is a military that’s politically entangled yet strategically naïve, a force that continues to insist on its neutrality while being used, seen, and perceived in highly political ways.

The consequences of professional detachment are no longer theoretical; they are unfolding in real time. The norms of American civil-military relations have always been delicate, but they rested on at least one fundamental consensus: that the military would not be used as a prop for partisan politics, especially not on domestic soil. That consensus was largely shattered at Fort Bragg yesterday afternoon. What was billed as a celebration of the Army’s 250th anniversary became a campaign rally in all but name.12 President Trump used the occasion to denounce protesters in Los Angeles as “animals” and “a foreign enemy,” while pledging to “liberate” the city using military force.13 Uniformed soldiers applauded from the crowd. Vendors sold Trump hats and shirts on base property.14 Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth spoke about restoring the “warrior ethos” and mocked the idea that the military should concern itself with political correctness.15 Army Secretary Dan Driscoll called Trump “the greatest recruiter in our Army’s history.”16

This was not just another round of “bad optics.” It was the most serious breach of American civil-military norms in the 21st century. A sitting president, flanked by his political appointees, using a U.S. military base and its personnel as the backdrop for a speech that not only threatened domestic protesters but cast entire American cities more or less as occupied territory. The audience, composed of service members and their families, cheered. The attempt by leaders on the base to control appearances, ensuring no one in uniform showed dissent, only magnified the appearance of complicity.17

It should be noted that the crowd at the event was relatively small, only a few hundred people, and the group of uniformed soldiers positioned behind the president and in view of the cameras was carefully selected. But that’s precisely the problem. The staging was deliberate. The event was choreographed to project the illusion of broad military endorsement, even though most of the force had no direct involvement in it. In doing so, it exploited the visual authority of the uniform to serve partisan aims while insulating the broader institution from direct accountability. The small size of the crowd doesn’t diminish the seriousness of what happened; it underscores it. A narrow, curated image was used to send a wide political message, leveraging the military’s public trust for political theater. And because the institution allowed itself to be used in this way, however selectively, the perception of complicity still spreads across the entire force.

Army leaders on base were very aware of the optics. That much is obvious. What they failed to grasp, naively or recklessly, was the political gravity of what they were staging. Rather than tolerating the possibility of a few eye rolls or quiet non-reactions from the troops, the event was managed to achieve complete uniformity. And in doing so, it crossed a line supposed to be restrained by what Huntington called the “military ethic.”18 A brief news cycle about soldier discomfort could have passed in a day. Instead, what Americans saw was an obedient crowd of soldiers cheering a speech that labeled fellow citizens as enemies and promised military action against them. That may linger for years, depending on how the events unfold.

It’s tempting to dismiss all this as a one-off: a particularly theatrical event by a particularly theatrical president. But that mindset is precisely what allows the erosion to continue. Each time something like this happens, soldiers cheering at campaign-style events, National Guard units deployed over the objections of governors, political appointees using warfighter rhetoric to rally their base, it gets rationalized as a fluke. The damage, however, is cumulative. Every incident nudges the public further toward believing the military is no longer neutral, that it belongs to one side. Once that belief hardens, it’s nearly impossible to undo.

These events teach the public and future political leaders that it’s acceptable to use the military for domestic political ends, as long as it’s wrapped in the language of order and patriotism. That lesson is corrosive. It dissolves the line between military loyalty to the Constitution and personal loyalty to a political figure. And it conditions troops to view domestic political dissent not as part of democracy, but as an internal threat to be managed.

What this attitude fails to grasp is that legitimacy in civil-military relations is as much about perception as it is about principle. Once the perception of neutrality is lost, every military action, no matter how routine, becomes politically suspect. That suspicion will erode public trust, invite greater political oversight, and create pressure for the military to align more explicitly with one political coalition or the other. The real danger is not that the military will be forcibly politicized, it’s that it will slide into politicization by inertia.

In this way, the apolitical military isn’t only vulnerable to politicization, but it also enables it. When leaders refuse to articulate boundaries or speak out against violations of norms and traditions, they create a vacuum. That vacuum is quickly filled by political actors eager to wrap themselves in the flag and the camouflage. The more often this happens, the more inevitable it becomes that one side will demand a politically loyal military to offset the perception that it was previously loyal to the other.

This is how bipartisan trust dies, not with a coup, but with complicity, silence, and repetition. The military’s reputation for professionalism has long stood as one of the few remaining pillars of institutional legitimacy in American public life, consistently ranking as the most trusted of all government institutions.19 But that reputation only holds if the military actively defends its neutrality, not just by refusing unlawful orders, but by resisting politicized symbolism. When the military says nothing while a president calls American cities “foreign enemies” and promises to use troops to intimidate protesters, neutrality becomes a pose, not a principle.

The collapse of the consensus around military neutrality is hazardous because it is happening asymmetrically. While many in the officer corps still speak in the language of restraint and constitutional duty, political actors have become bolder in testing those limits. The result is an imbalance. One side pushes. The other stays silent. And the ratchet turns. The irony is that a truly apolitical military actually requires politically aware leadership. Preserving neutrality demands that officers understand when it is being compromised, not just in the courtroom, but in the public square. That means developing an internal culture that includes fundamental political literacy, not partisanship, but fluency in democratic norms, civilian control, and the dangers of institutional capture.

The problem isn’t that the military has suddenly been hijacked. The problem is that the structures meant to prevent politicization have atrophied. Apolitical professionalism has been used as a shield for disengagement, a reason to do nothing, a license to let others define what “supporting the troops” looks like. And in that vacuum, the meaning of professionalism has been redefined by those with very political agendas.

But civil-military relations are a two-way street. In a democratic republic, ultimate responsibility lies with elected civilian officials, and they have increasingly abdicated that responsibility, or worse, weaponized the military for partisan aims. From President Bush’s “mission accomplished” stunt in 2003 to President Obama's announcement of his strategy for Afghanistan at West Point in 2011, to President Biden having uniformed Marines in the background for a speech aimed at democracy in 2022 but flavored with partisan talking points, there is a very logical path to the events of the last week.

The dysfunction is not limited to the armed forces sleepwalking into politicization; it is magnified by civilians who either don’t understand the military or cynically exploit its authority. For every scholar-practitioner like Carter Malkasian and Edward Lansdale, who engages seriously with the political complexity of modern conflict, there are a hundred officers like Captain Tom Cotton, Major Pete Hegseth, or David Hackworth molded by a system that prioritized battlefield aggression and ideological certainty over strategic thinking and ethical reflection.20 Their outlook was never shaped by Clausewitz or civil-military theory, but by the belief that success was a matter of willpower and firepower, that if we had only killed more “military-aged males,” the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan surely would have been won.21

That dehumanizing phrase, “military-aged males,” has since migrated from battlefield jargon to civilian political discourse. Governor Kristi Noem recently used it in a letter to Pete Hegseth requesting military assistance, framing entire populations as threats to be neutralized rather than citizens to be governed.22 It is a telling example of how political figures increasingly adopt military language without grasping its implications. This kind of rhetoric transforms complex social and political challenges, migration, civil unrest, and crime into warfighting problems and calls for military solutions as if violence were a policy panacea.

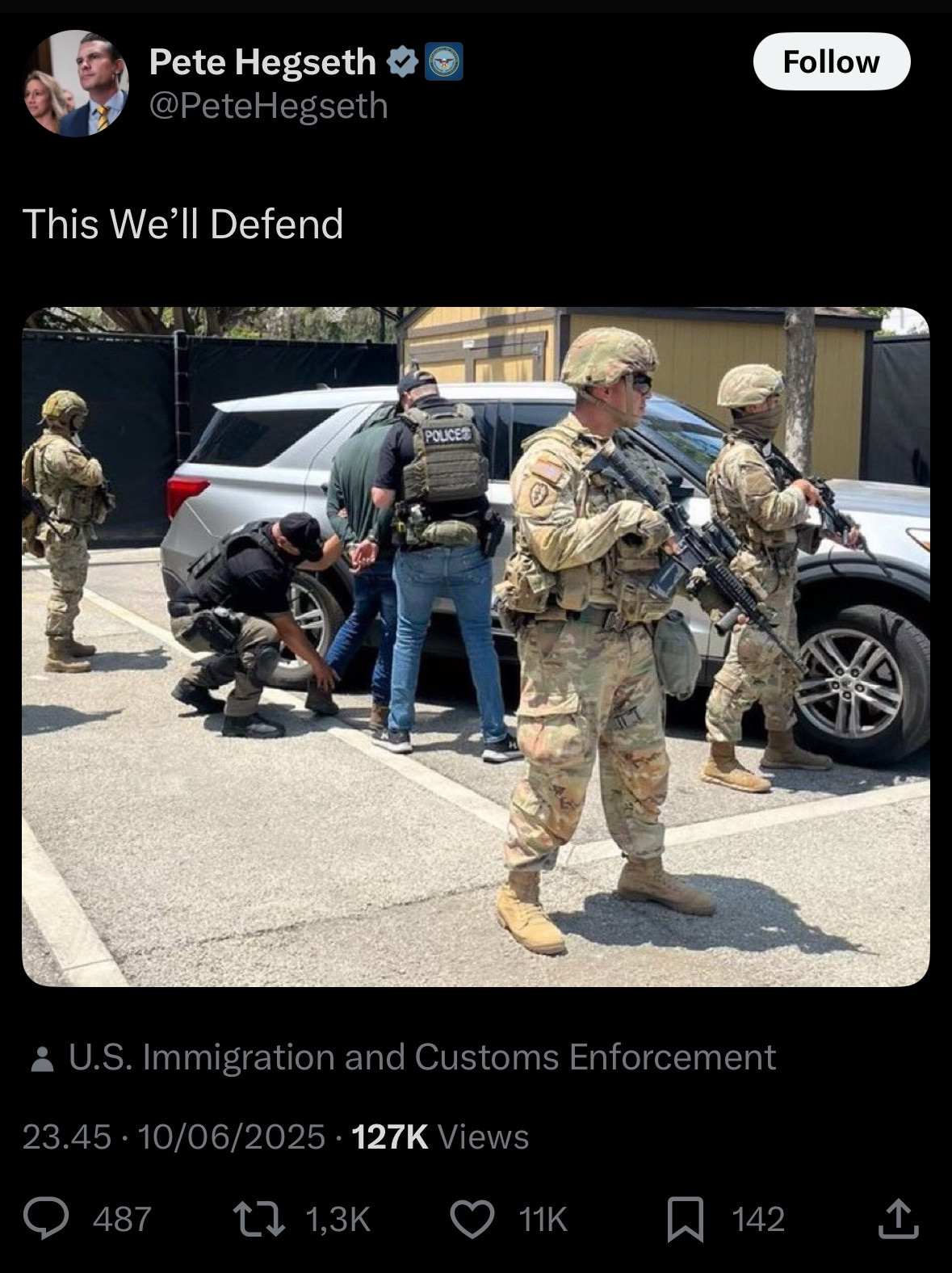

At the end of the day, it is the prerogative of figures like Cotton, Noem, and Hegseth to act as partisans. That’s politics, and as elected officials or political appointees, they are well within their rights to promote their views. The problem isn’t that they hold ideological positions or advocate a particular vision of military strength or national identity—it’s that their personal crusades are often embraced uncritically by segments of the Army and the political establishment, and they are routinely elevated as representative voices of military experience. When Hegseth reposts a photo of what appears to be a staged law enforcement arrest featuring a soldier with a 25th Infantry Division patch pulling security in the background, a unit with a combat lineage spanning World War II through Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, it signals a dangerous conflation of military authority with domestic law enforcement. Figures like Cotton and Hegseth have become avatars of “the veteran perspective,” shaping public discourse in ways that equate partisan aggression with patriotism, reduce complex conflicts to simplistic body counts, and frame dissent or strategic restraint as weakness rather than wisdom.

Underlying this worldview is a distinctly GWOT-era mentality, the belief that “a show of force” and theatrical displays of power can resolve inherently political and social problems at home.23 This mindset, forged during two decades of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism, views strength as a spectacle and assumes that showcasing force will somehow substitute for legitimacy, strategy, or institutional trust. It’s the same logic that powered the troop surges and drone campaigns of the 2000s: escalate hard enough, hit fast enough, kill sufficiently, and the problem will magically go away. Cotton, Hegseth, and many other veteran politicians have become public standard-bearers for this way of thinking. To them, failure is never a matter of flawed assumptions or misapplied force—it simply means not having used enough of it. More troops. More raids. More “military-aged males” eliminated.

The danger becomes even greater when that logic is applied at home. When unrest, protest, or dissent is met not with political engagement but with calls for military deployments and shows of force, the response is no longer just misguided—it becomes a threat to democratic norms. The belief that you can restore order by dominating the streets without understanding what caused the unrest in the first place isn’t a strategy. It’s a fantasy. And it’s one we’ve seen before.

When civilian leaders start talking like junior officers and junior officers elected to office start acting like partisan surrogates, the boundary between military and political life collapses. The military is no longer a tool of last resort used judiciously by responsible civilians; it has become an ever-present instrument of domestic policy, national identity, and political signaling. And when this happens, it doesn't just erode civil-military norms. It fosters a feedback loop where militarism feeds political dysfunction and political dysfunction demands more militarism in return.

Ultimately, civil-military breakdown is not caused by one side alone. The failure lies in the reciprocal irresponsibility of civilians who romanticize or instrumentalize the military and of military leaders who fail to push back, out of ignorance, fear, or ambition. Neither the warrior nor the statesman can afford to operate in isolation from the consequences of their actions. When both sides treat the military as either a cultural symbol or a blunt instrument, the democratic control of force becomes ornamental, and democracy itself more brittle.

The erosion of civil-military norms we are witnessing is neither sudden nor accidental; it is the predictable outcome of years of complacency, opportunism, and willful ignorance on both sides of the civil-military divide. The American military’s claim to nonpartisanship can no longer rest on ceremonial distance from politics, given that its image and force are repeatedly used for domestic political gain. True neutrality requires vigilance, institutional memory, and the moral courage to draw lines before they are crossed. If the military does not confront the political gravity of its actions, and if civilian leaders continue to exploit the military’s symbolic capital for partisan aims, then the United States will find itself with an armed force that is no longer trusted by the people it serves. And once that trust is gone, no amount of ritual, uniform, or rhetoric will restore it. What comes next is not just politicized force, but a political system that is more fragile, more volatile, and more prone to collapse under the weight of its own illusions.

ERIC THAYER, MORGAN LEE and MICHELLE L. PRICE, “Trump deploys California National Guard to LA to quell protests despite the governor’s objections,” AP News, June 8, 2025.

Samuel Huntington, The Soldier and the State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957),

William E. Rapp, "Civil-Military Relations: The Role of Military Leaders in Strategy Making." Parameters (2015): 13.

Huntington, 8.

John Binkley, “Clausewitz and Subjective Civilian Control: An Analysis of Clausewitz's Views on the Role of the Military Advisor in the Development of National Policy,” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 42, No. 2 (2016), 251.

There have been many critiques of this model, for example, see Risa Brooks, "Paradoxes of Professionalism: Rethinking Civil-Military Relations in the United States." International Security, (2020); 7-44, Suzanne C. Nielsen and Don M. Snider, American Civil-Military Relations: The Soldier and the State in a New Era (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), Robert Williams, “It’s Time to Ditch Huntington,” Small Wars Journal, February 6, 2025, Carsten F. Roennfeldt, “Wider Officer Competence: The Importance of Politics and Practical Wisdom,” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 45, No. 1 (2019): 59–77, Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime (New York: Free Press, 2002), and Peter Feaver, "The Civil-Military Problematique: Huntington, Janowitz, and the Question of Civilian Control," Armed Forces & Society 23, no. 2 (1996); 149-170.

See H.R. McMaster, Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam (New York: Harper-Collins, 1998); 407-434.

Huntington, 11-22.

See Peter Feaver, "Crisis as Shirking: An Agency Theory Explanation of the Souring of American Civil-Military Relations." Armed Forces and Society 24, no. 3 (1998); 407-434.

Peter Feaver, "The Right to Be Right: Civil-Military Relations and the Iraq Surge Decision." International Secuirty 35, no. 4 (2007); 87-125 and Andrew Payne, "Bargaining with the Military: How Presidents Manage the Political Costs of Civilian Control." International Security 48 (1), (2023); 166-207.

Andrew Milburn. "Breaking Ranks: Dissent and the Military Professional." Joint Forces Quarterly (2010): 101-107.

You can watch the full speech here:

Chris Megerian and Michelle Price, “Trump Says He Will ‘Liberate’ Los Angeles in Speech to Mark the 250th Anniversary of the Army,” AP News, June 10, 2025.

Konstantin Toropin and Steve Beynon, “Bragg Soldiers Who Cheered Trump's Political Attacks While in Uniform Were Checked for Allegiance, Appearance,” Military.com, June 11, 2025.

I wrote about this problem in The Rise of American Bushido and American Bushido in Practice

Ibid,.

Toropin and Beynon.

Huntington, 62. He more or less defines the military ethic as a professional, apolitical, and conservative code rooted in obedience, discipline, and the management of violence, with a strict separation from civilian political life.

The lowest U.S. confidence in the military has recently reached 60%, which is well above the confidence in most other government institutions. See April Rubin, “U.S. confidence in military hits a 20-year low,” Axios, April 1, 2023.

See Carter Malkasian, The American War in Afghanistan: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021) and Max Boot, The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018).

For example, Cotton wrote a glowing review of Triumph Regained, The Vietnam War, 1965-1968 by Mark Moyer, a revisionist Vietnam War book that essentially argues the United States was just a few more body counts away from victory.

Dan Gooding and Hannah Parry, “Kristi Noem Urged Pete Hegseth and US Military to Arrest LA Rioters,” Newsweek, June 10, 2025.

Tom Cotton, “Tom Cotton: Send In the Troops, for Real,” Wall Street Journal, June 10, 2025.

Great post.

I may be personally biased, but I think the United States and its Armed Forces could learn some lessons from countries like the Federal Republic of Germany, that have their own histories of politically abused armed services.

Germany ever since the Second World War made sure its soldiers were not apolitical tools, but citizens in uniform with their own conscience and political literacy, who have sworn to defend the constitutional order and the values of the Bundesrepublik

Not great Bob!